If you read the last post, you know what’s going on. Here are a few more reasons why I enjoy western movies:

Besides the gritty mood and aesthetics, I like the fact that westerns usually have something to say about America (and, in the case of spaghetti westerns, about Italian politics as well).

Some horse operas are deliberately celebratory and nostalgic, emphasizing either conservative or liberal values at the core of US history. Others are more critical, explicitly denouncing past crimes or acting as metaphors for contemporaneous issues, like McCarthyism, civil rights, or the Vietnam War. Even when they don’t have a clear message, western films tend to illustrate elements of American identity such as individualism, gun culture, and paranoid frontier status.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and High Noon are not only a joy to watch, but also interesting to decipher politically (the latter is especially fun if you try to read in it a premonitory allegory about Batman comics, since it involves the vengeful return of a terrifying thug called Frank Miller). Tonino Valerii’s The Price of Power is, oddly, a western about the JFK assassination (yep). Some people even claim Django Unchained is about racism, but then again people see racism everywhere nowadays.

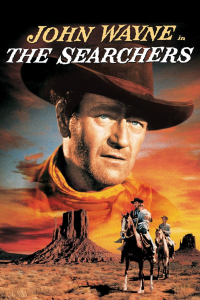

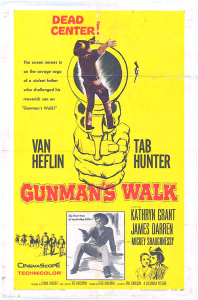

Speaking of racism, classic westerns do have quite a poor track record in terms of depicting Native Americans. They started addressing this issue in increasingly complex ways in the 1950s… John Ford’s The Searchers has a reputation for being a provocative revisionist take on the matter, but I don’t think the movie earns it. As far as I’m concerned, the unappreciated Dakota Incident and Gunman’s Walk do a much better job!

But of course, if we’re talking about westerns and politics, then we cannot escape Mexico…

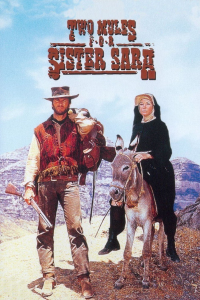

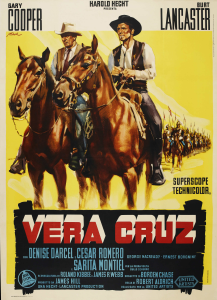

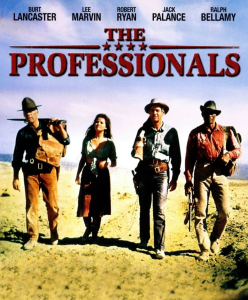

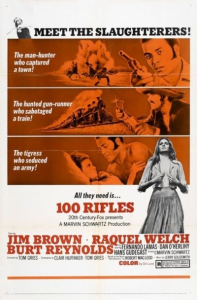

There are just so many awesome yarns south of the border – and they often get down and dirty in Mexico’s bloody history! Even if you leave out the Franco-Mexican War (the setting for the amusing Vera Cruz and Two Mules for Sister Sara) and just focus on the Mexican Revolution, you have the bigger-than-life The Wild Bunch, the compellingly schlocky 100 Rifles… the list goes on, but ultimately none of them beats Richard Brooks’ The Professionals, which is an all-out adventure romp with a particularly delicious closing line.

(Brooks later did the proto-western Bite the Bullet, which is not about Mexico but it also finishes on an anti-capitalist note.)

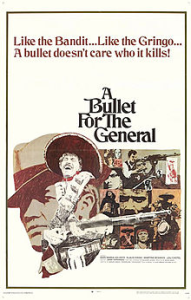

Furthermore, there is a whole subgenre of revolutionary Italian oaters – the ‘Zapata westerns’. They’re usually about some gringo getting involved in the Mexican civil war and feature the kind of sadism you’d expect from late ’60s Italian cinema. Some seem more militant, like A Bullet for the General, while others look more like an excuse to blow stuff up, like The Mercenary, but I’m not going to lie: I dig them all. Yes, even with the uneven acting and the fucked up sexual politics. Maybe it’s the cheesy sentimentality that does it for me, but most likely it’s those hauntingly weird soundtracks.

Finally, the geek in me loves the fact that this is a genre that constantly builds on itself. For instance, Edward L. Cahn’s Law and Order, John Sturges’ Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and Edward Dmytryk’s Warlock are all different variations of the legend of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday (and they are all excellent).

Like superhero stories, many westerns are part of an evolving intertextual dialogue, citing, revising, updating, and/or paying homage to their predecessors… Contrary to comics, though, you’re not actually expected to have a degree in the genre’s history and spend a fortune on auxiliary titles just to follow the plot!

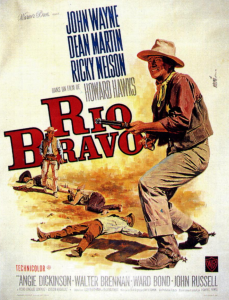

Still, this self-referential dimension can be quite rewarding for those in the inner circle. I guess the most famous example is how Fred Zinnemann did a downbeat picture about a frustrated sheriff looking for help defending his town from outlaws (High Noon) and Howard Hawks responded by doing a badass flick about a fearless sheriff in the same situation who just shuts up and takes care of business (Rio Bravo).

Critics are also fond of pointing out that Hawks kind of remade Rio Bravo as the entertaining El Dorado and once again as the lamer Rio Lobo… That is true but it misses the larger point that Rio Bravo was itself basically a loose variation of Hawks’ classic adventure drama Only Angels Have Wings. So in this case I think it’s less about westerns commenting on each other than about the fact that Hawks just really liked to tell stories about manly professionals of different generations carrying out their work in inhospitable conditions and about women trying to pierce through their stoic exterior (he went on to revisit this formula in the very lighthearted romantic drama Hatari!).

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

There’s more. You get an extra kick out of watching Unforgiven if you’ve seen any other western with Clint Eastwood before… Also, you can find plenty of metafictional layers in the work of Sergio Leone. His Once Upon a Time in the West is full of winks to the classics. Duck, You Sucker is Leone’s answer to the Zapata westerns. And he was heavily involved in My Name Is Nobody, which is basically a clash between an old-school spaghetti western and the then-new brand of fagioli western comedies.

This brings us to The Hateful Eight, which I think combines all the elements that make westerns great. Quentin Tarantino delivers tense Mexican standoffs, violent shootings, and an Ennio Morricone score, while also bringing in elements of other genres (mystery, horror, dark comedy). The titular eight characters who hate each other for various reasons, stuck together in a cabin during a blizzard, provide a simple, minimalistic set-up that enables a quasi-parable about larger themes. Above all, the film offers a meditation on the messed up history of complicated racial relations in the United States, ultimately seeking a glimmer of hope in Abraham Lincoln’s legacy (real or fictitious). And, needless to say, Tarantino pays a heartfelt homage to the history of the genre itself, from the Hawksian sense of claustrophobia to the snowbound visuals of the bleak The Great Silence and the underrated Day of the Outlaw.

Day of the Outlaw (1959)

Day of the Outlaw (1959)

Regarding comics, if we’re talking mean-spirited westerns, I quite like Hermann Huppen’s Wild Bill is Dead, which is a revenge tale that takes quite a detour. Hermann had drawn a bunch of westerns before (in the Comanche series), but this was the first one done in the stunning style he began experimenting with in the 1990s, with beautiful watercolors. He also wrote it – and while there is nothing particularly original or charming about Hermann’s scripts, this old-school Belgian author knows how to spin a two-fisted yarn. In that sense, Wild Bill is Dead belongs next to other gritty adventures he has crafted as a pretext to explore different landscapes and political issues, including Afrika, Caatinga, and the more surrealist Sarajevo Tango.

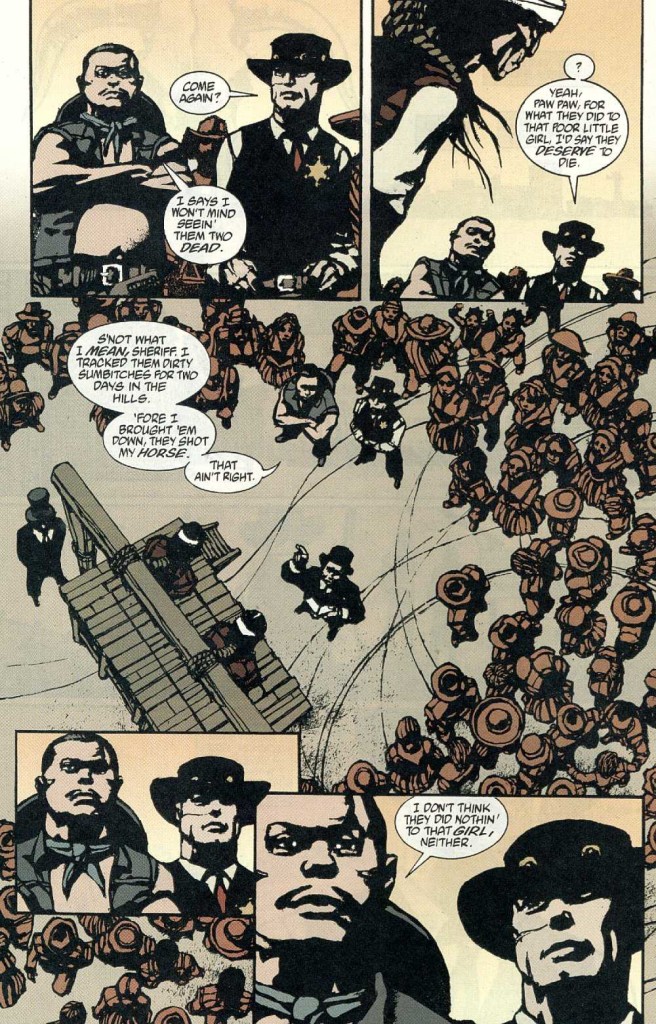

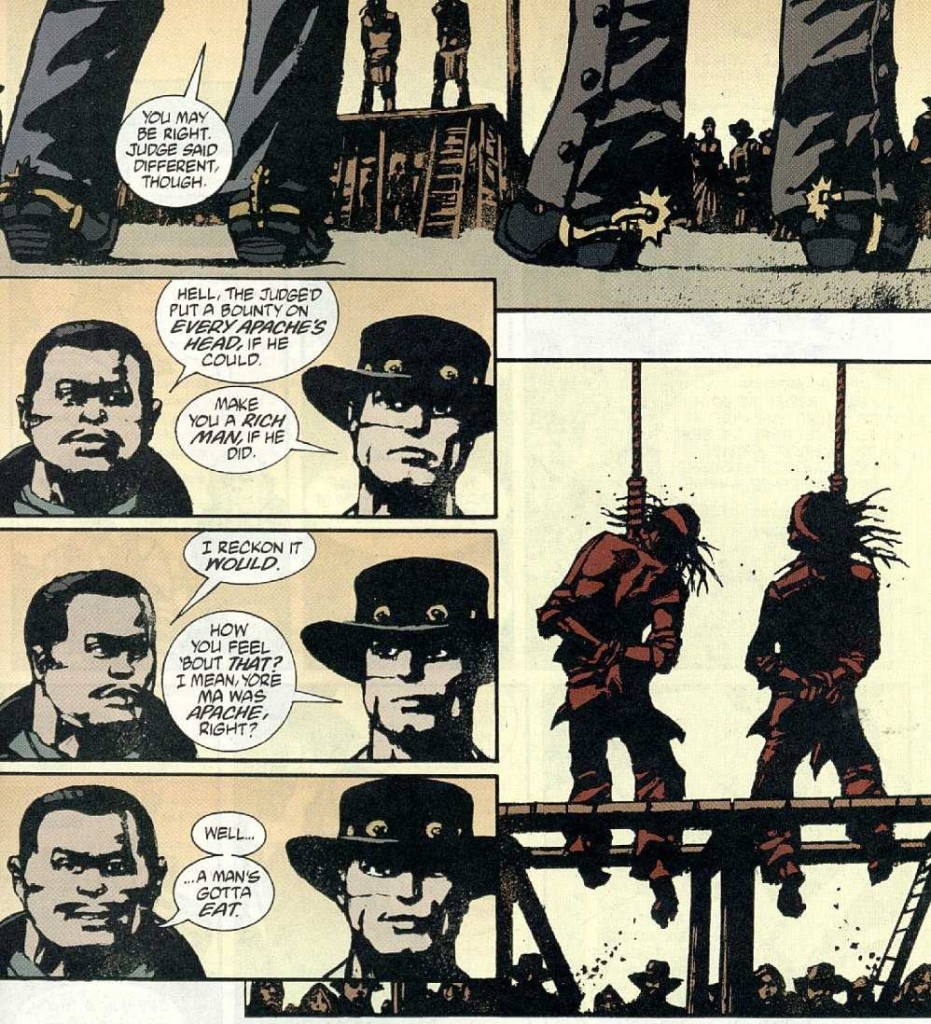

That said, The Hateful Eight’s flair for sardonic dialogue and the focus on post-Civil War racial issues points more sharply to Loveless, by Brian Azzarello, Marcelo Frusin, and Danijel Zezelj. This series had its moments, but it took way too long to find its feet, so instead I’ll recommend Azzarello’s and Zezelj’s less ambitious El Diablo. It’s a neat little western that for a while seems to be about a manhunt, but it has splashes of horror and noir, not to mention a handful of plot twists up its sleeve.

El Diablo

El Diablo

NEXT: Batman makes a splash.