It’s been a while since I’ve discussed books without pictures in this blog… And since the world seems to be struggling to return to a form of normality these days, let’s have a look at a couple of remarkable novels about adapting to distorted perspectives on reality:

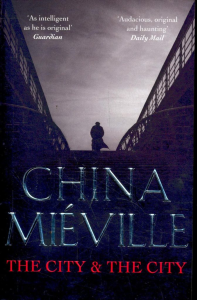

THE CITY & THE CITY

(China Miéville, 2009)

“I could not see the street or much of the estate. We were enclosed by dirt-coloured blocks, from windows out of which leaned vested men and women with morning hair and mugs of drink, eating breakfast and watching us. This open ground between the buildings had once been sculpted. It pitched like a golf course – a child’s mimicking of geography. Maybe they had been going to wood it and put in a pond. There was a copse but the saplings were dead.

The grass was weedy, threaded with paths footwalked between rubbish, rutted by wheel tracks. There were police at various tasks. I wasn’t the first detective there – I saw Bardo Naustin and a couple of others – but I was the most senior. I followed the sergeant to where most of my colleagues clustered, between a low derelict tower and a skateboard park ringed by big drum-shaped trash bins. Just beyond it we could hear the docks. A bunch of kids sat on a wall before standing officers. The gulls coiled over the gathering.

‘Inspector.’ I nodded at whomever that was. Someone offered a coffee but I shook my head and looked at the woman I had come to see.

She lay near the skate ramps. Nothing is still like the dead are still.”

A cross between noirish police procedural and the branch of speculative fiction known as New Weird, The City & The City expertly applies a highly familiar formula to an utterly counter-intuitive setting (although nowhere nearly as baffling as the one in this post’s second book). Before spoiling what makes the East European city-state of Besźel so special, let me underline how much I love this sense of double mystery (who killed the woman and how the hell does this whole place operate?). Using a murder investigation to lead readers around an alternate reality while speculating about what kind of inventive crimes could take place there is a popular trope and there are good reasons for it – after all, such narrative framework gives the protagonists freedom of movement to go to very different locations, interrogate multiple people, and uncover hidden dimensions of this imaginary world, more often than not revealing an earth-shattering conspiracy (among many successful examples, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union and the Felix Castor series come to mind, as does Who Framed Roger Rabbit).

Still, to properly pull it off you need to excel on both levels: fleshing out the stock situations in the core plot (clever detective work, interesting motivations) and selling all the new rules to the reader (intriguing premise, thoughtful world-building). Fortunately, China Miéville knows what he’s doing. As you can tell from the passage above, his prose is quite pacy, but it’s also full of details conveying Besźel’s overall authenticity and materiality. I find these particularly witty when it comes to the local (fictional) culture and language. One of my favorite bits concerns a brief etymology of the ethnic slur ‘ébru’:

“Technically of course the word was ludicrously inexact for at least half of those to whom it was applied. But for at least two hundred years, since refugees from the Balkans had come hunting sanctuary, quickly expanding the city’s Muslim population, ébru, the antique Besź word for ‘Jew,’ had been press-ganged into service to include the new immigrants, become a collective term for both populations. It was in the Besźel’s previously Jewish ghettos that the Muslim newcomers settled.

Even before the refugees’ arrival, indigents of the two minority communities in Besźel had traditionally allied, with jocularity or fear, depending on the politics at the time. Few citizens realise that our tradition of jokes about the foolishness of the middle child derives from a centuries-old humorous dialogue between Besźel’s head rabbi and its chief imam about the intemperance of the Besźel Orthodox Church. It had, they agreed, neither the wisdom of the oldest Abrahamic faith, nor the vigour of its youngest.”

The book takes three or four chapters before it properly addresses Besźel’s highly idiosyncratic condition, even if China Miéville drops hints since early on. If you happen to come to the story cold, it’s fun to gradually uncover the secret hidden in what at first may appear to be quite a straightforward – even clichéd – tale.

In case you prefer to know more before diving in: the gist of it is that Besźel is actually one of two post-Soviet city-states that occupy much of the same space simultaneously, yet the division isn’t linear like in cold-war Berlin or Nicosia – the cities are quite geographically entwined, which means that the citizens of each political entity coexist with the ones on the other state while constantly avoiding perceiving each other. In other words, everyone instinctively erases from their consciousness – ‘unsees’ and ‘unhears’ – the denizens and buildings from the ‘other’ city. (Yep, it’s as if Miéville has expanded a chapter from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities into an intricate thriller!)

This high concept raises a lot of questions, of course, and it’s to the writer’s credit that he manages to engage with many of them without resorting to infodumps, as the story keeps spreading into new directions. I heard there was a BBC show adapting the tale to television, but I’m not eager to watch it. This is such an odd premise that a big part of what makes The City & The City so entertaining is trying to wrap your head around the whole thing – I’m sure the story loses a lot if someone else visualizes the setting for you.

Then again, the point is that the concept ultimately isn’t all that odd, since we are programmed to selectively disregard so much of the world around us anyway, particularly those things (and people) whose existence drastically challenges our convictions. While it’s tempting to see in the book an imaginative allegory about Jerusalem, apartheid, nationalism or state borders in general, I kept thinking about the process of ‘unseeing’ the homeless, refugees, and abuse victims on a daily basis. Even in ostensibly unified cities, some neighborhoods are treated as if they belong to a whole other country. In a classic sci-fi move, Miéville pushes aspects of modern urban life and alienation to a new extreme, touching on a number of political and existential issues along the way.

All in all, this is a thoroughly engaging page-turner, not just because of the challenge of figuring out the murder mystery alongside Inspector Tyador Borlú and Constable Lizbyet Corwi, but also because you have to keep trying to cope with their fascinatingly off-kilter perspective…

“I watched the local buildings’ numbers. They rose in stutters, interspersed with foreign alter spaces. In Besźel the area was pretty unpeopled, but not elsewhere across the border, and I had to unseeing dodge many smart young businessmen and –women. Their voices were muted to me, random noise. That aural fade comes from years of Besź care. When I reached the tar-painted front where Corwi waited with an unhappy-looking man, we stood together in a near-deserted part of Besźel city, surrounded by a busy unheard throng.”

THE INFERNAL DESIRE MACHINES OF DOCTOR HOFFMAN

(Angela Carter, 1972)

“I remember everything.

Yes.

I remember everything perfectly.

During the war, the city was full of mirages and I was young. But, nowadays, everything is quite peaceful. Shadows fall only as and when they are expected. Because I am so old and famous, they have told me that I must write down all my memories of the Great War, since, after all, I remember everything. So I must gather together all that confusion of experience and arrange it in order, just as it happened, beginning at the beginning. I must unravel my life as if it were so much knitting and pick out from that tangle the single, original thread of my self, the self who was a young man who happened to become a hero and then grew old.”

Following a bizarre magical war that warped reality beyond recognition, distorting the time and space of an unnamed Latin American city, Angela Carter’s The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman – published in the United States as The War of Dreams – is told in the form of the memoirs of Desiderio, an employee of the Ministry of Determination, which sought to somehow preserve order among all the chaos. It follows Desiderio’s globetrotting quest to defeat the mysterious Doctor Hoffman (the mad genius behind the attack) while being haunted, in dreams, by the Doctor’s daughter, Albertina.

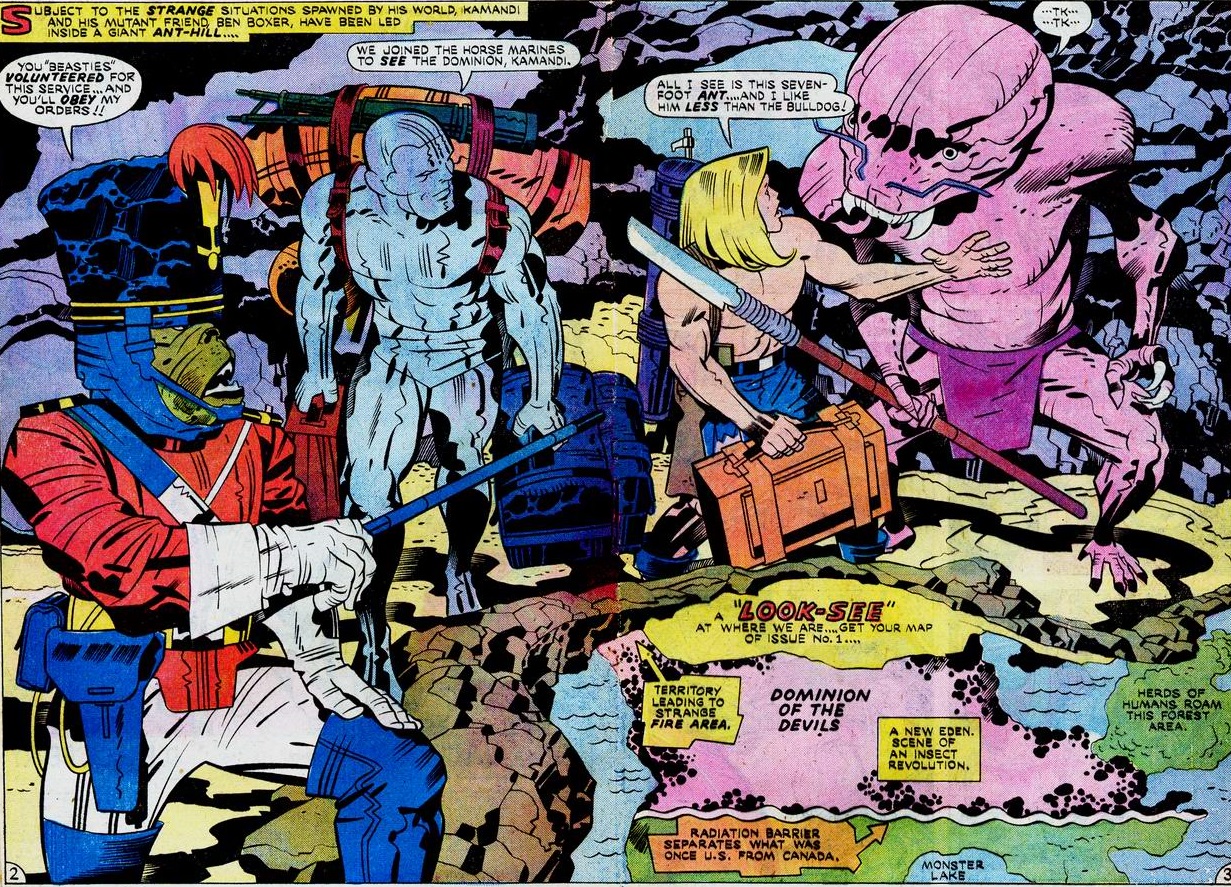

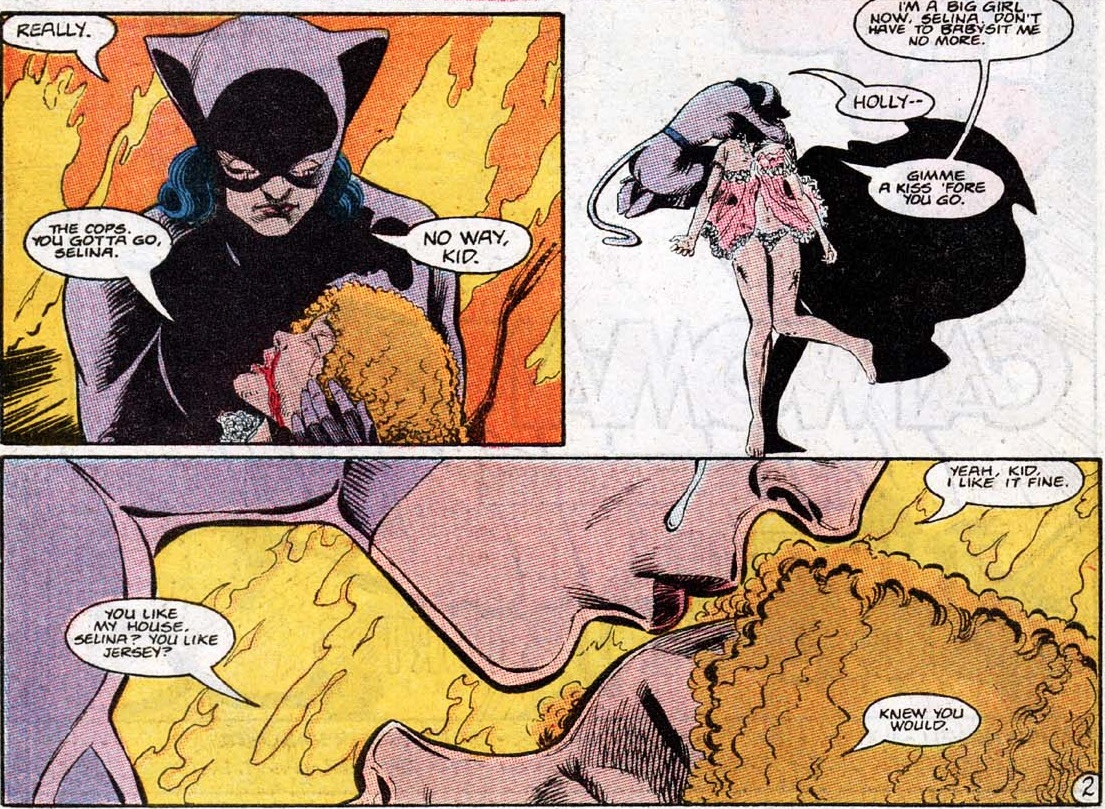

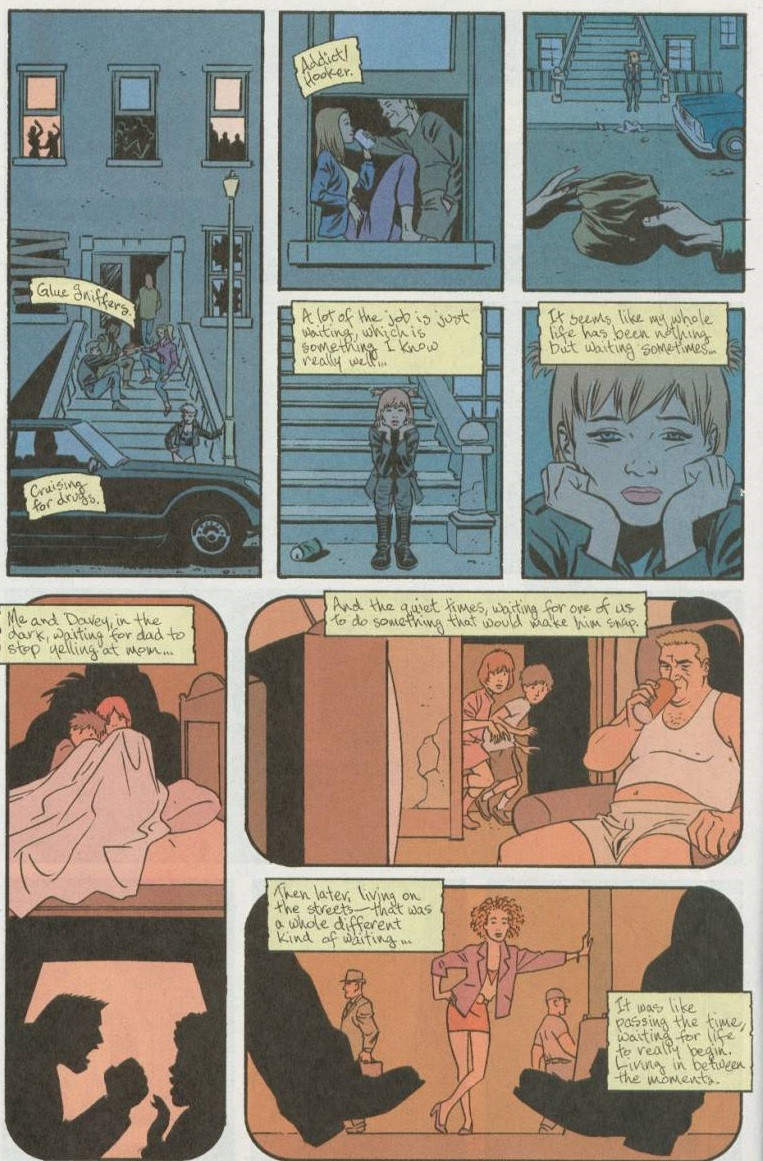

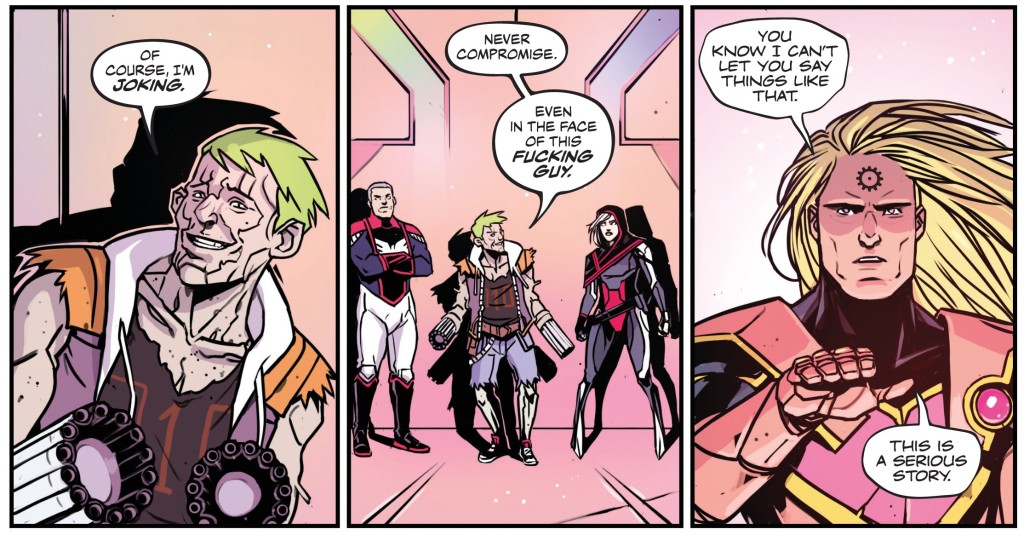

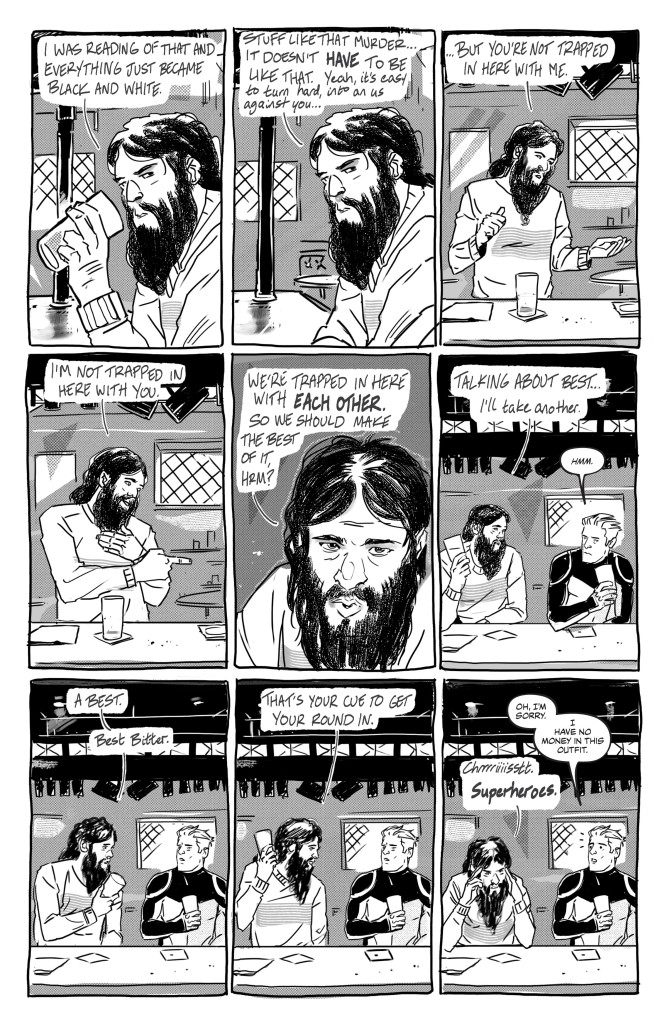

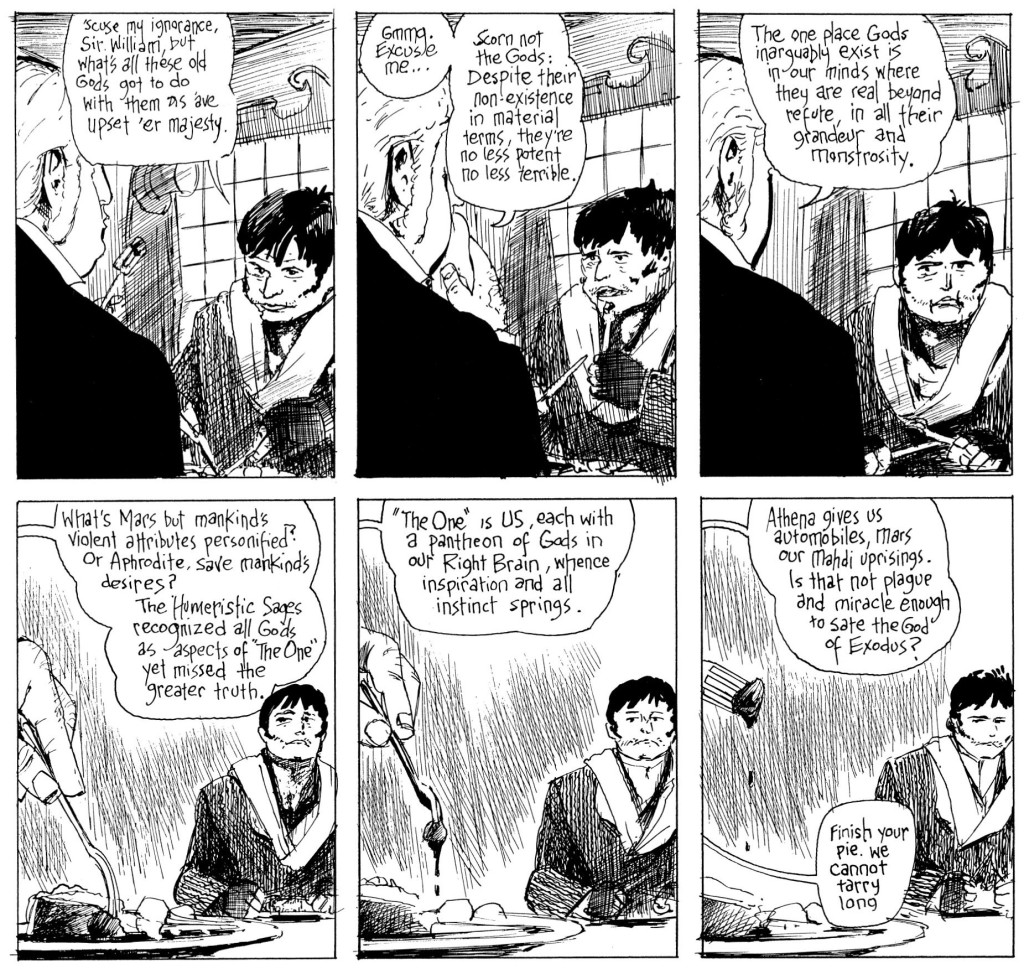

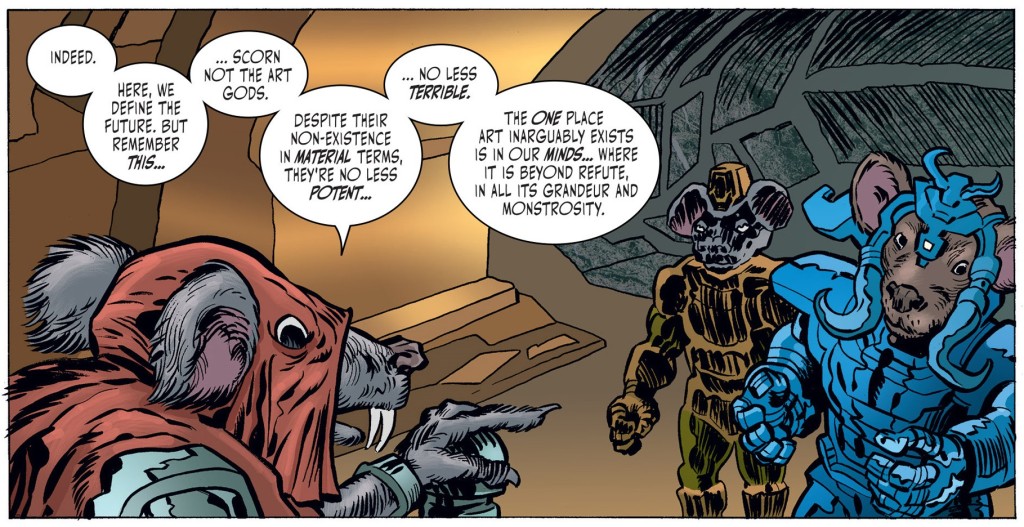

This is an articulate adult fantasy novel that dives deep into trippy surrealism (Ali Smith’s introduction to my edition claims the name of Desiderio’s antagonist alludes to a German romantic writer called E.T.A Hoffmann and perhaps also to the psychiatrist Heinrich Hoffmann, but surely the creator of LSD, Albert Hofmann, was also on Carter’s mind…). Imagine a colorful hybrid of poetry, adventure yarn, gothic horror, pornography, and philosophical allegory. The amusing, mind-boggling tone and postmodern sensibility bring to mind the wildest collaborations of Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy as well as Grant Morrison’s tales of reality-defining confrontations in The Filth, The Invisibles, and Doom Patrol. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn of Carter’s influence on that whole generation of comic book writers, not to mention on stuff like Xombi and Casanova.

A lot of it is filled with awesome descriptions like this one:

“The sense of space was powerfully affected so that sometimes the proportions of buildings and townscapes swelled to enormous, ominous sizes or repeated themselves over and over again in a fretting infinity. But this was much less disturbing than the actual objects which filled these gigantesque perspectives. Often, in the vaulted architraves of railway stations, women in states of pearly, heroic nudity, their hair elaborately coiffed in the stately chignons of the fin de siècle, might be seen parading beneath their parasols as serenely as if they had been in the Bois de Boulogne, pausing now and then to stroke, with the judiciously appraising touch of owners of race-horses, the side of steaming engines which did not run any more. And the very birds of the air seemed possessed by devils. Some grew to the size and acquired the temperament of winged jaguars. Fanged sparrows plucked out the eyes of little children. Snarling flocks of starlings swooped down upon some starving wretch picking over a mess of dreams and refuse in a gutter and tore what remained of his flesh from his bones. The pigeons lolloped from illusory pediment to window-ledge like volatile, feathered madmen, chattering vile rhymes and laughing in hoarse, throaty voices, or perched upon chimney stacks shouting quotations from Hegel. But often, in actual mid-air, the birds would forget the techniques and mechanics of the very act of flight and then they fell down, so that every morning dead birds lay in drifts on the pavements like autumn leaves or brown, wind-blown snow.”

Although wonderful to read in small doses, this type of writing could get tiresome after a while, but the book keeps reinventing itself, with Desiderio constantly encountering different milieus and dealing with new, eccentric characters… He travels with the circus, sails with pirates, and gets involved in horse chases. A couple of chapters read like a set of fascinating anthropological field notes: ‘The River People,’ in which Desiderio spends some time with a fictional Native American community, and ‘Lost in Nebulous Time,’ which has some of the greatest damn passages of fantasy I’ve ever read as he and Albertina cross an odd tropical forest (‘All the plants distilled poisons. This essential hostility was not directed at us or at any comer; the forest was helplessly, motivelessly malign.’) and run into a village of centaurs (‘They wore their genitalia set at the base of the belly, as on a man; because they were animals, they were without embarrassment but, because they were also men, even if they did not know it, they were proud.’).

These two chapters also include the novel’s most disturbing sequences (at least for my sensibilities). In fact, don’t be fooled be the apparently whimsical style of the earlier passages – The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman is a brashly debauched book and not for the faint of heart. If you’re into trigger warnings, assume all the main ones apply, from outdated stereotypes (yep, savage cannibals) to all sorts of broken sexual taboos!

There is an element of satire to the whole thing, albeit not the narrow, preachy kind. On a more immediate level, while presenting transcendent liberation as disturbing to mainstream bourgeois values, Angela Carter pokes fun at the reactionary forces trying to contain disruptive imagination in the name of organized capitalism. Moreover, there is a clear anti-authority strain running through the book, as both sides of the war seem to be run by tyrants. But Carter’s agenda is probably more sophisticated than this: she seems to be trying to capture the disorienting artificiality of life brough about by hedonistic consumerism and modern mass media, possibly inspired by Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (which came out a few years before).

Regardless, you don’t have to be into situationist critical theory in order to appreciate Carter’s prose. Anyone can have a blast with magnificent caricatures like the nihilistic, narcissistic Count, whom Desiderio meets along the way:

“He was particularly extraordinary in this: he had a passionate conviction he was the only significant personage in the world. He was the emperor of inverted megalomaniacs but he had subjected his personality to a most rigorous discipline of stylization so that, when he struck postures as lurid as those of a bad actor, no matter how ludicrous they were, still they impelled admiration because of the abstract intensity of their unnaturalism. He had scarcely an element of realism and yet he was quite real. He could say nothing that was not grandiose. He claimed he lived only to negate the world.

‘It is not in the least unusual to assert that he who negates a proposition at the same time secretly affirms it – or, at least, affirms something. But, for myself, I deny to the last shred of my altogether memorable being that my magnificent denial means more than a simple “no”. Sometimes my meagre and derisive lips seem to me to have been formed by nature only to spit out the word “no”, as if it were the ultimate blasphemy. I should like to speak an ultimate blasphemy and then bask in the security of eternal damnation but, since there is no God, well, there is no damnation, either, unfortunately. And hence, alas, no final negation. I am the hideous antithesis in person and I swear to anyone who wants the word of a hereditary count of Lithuania for it that I am not in the least secretly benignly pregnant with any affirmation of any kind whatsoever.’”