Although Frank Miller is best known for his world-shattering – and controversial – takes on Batman since the 1980s, he has been doing comics about Superman for just as long… and his approach to the Man of Steel is actually quite thematically rich in terms of his depictions of both the ‘super’ and the ‘man’ sides of the character.

Let’s start with the ‘super’ angle – that is to say, with the dimension that transcends humanity. I don’t mean the super powers, like flying or shooting lasers out of the eyes; I mean Superman’s larger-than-life symbolic potential, which Miller began exploring as early as his masterpiece The Dark Knight Returns, back in 1986.

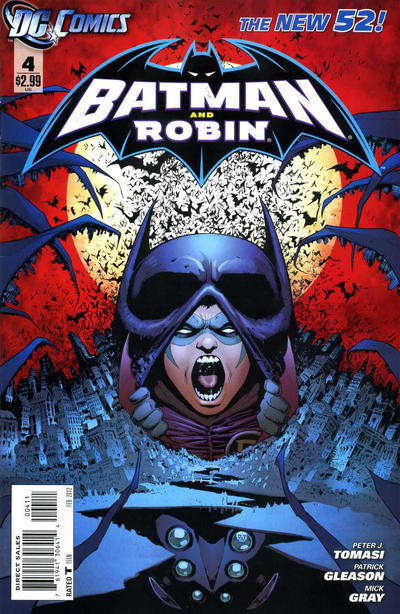

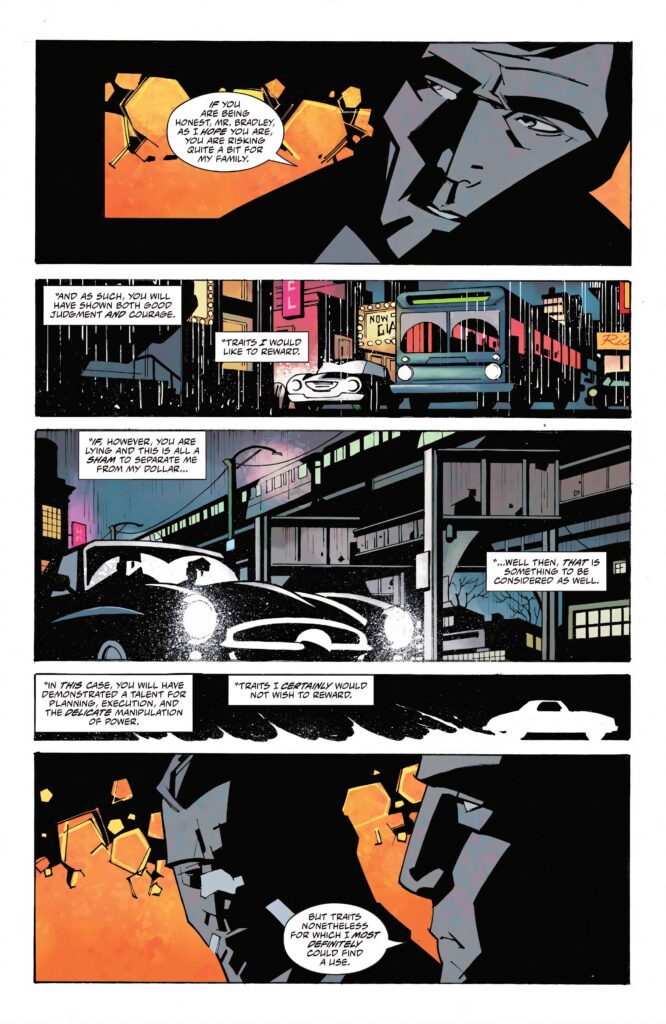

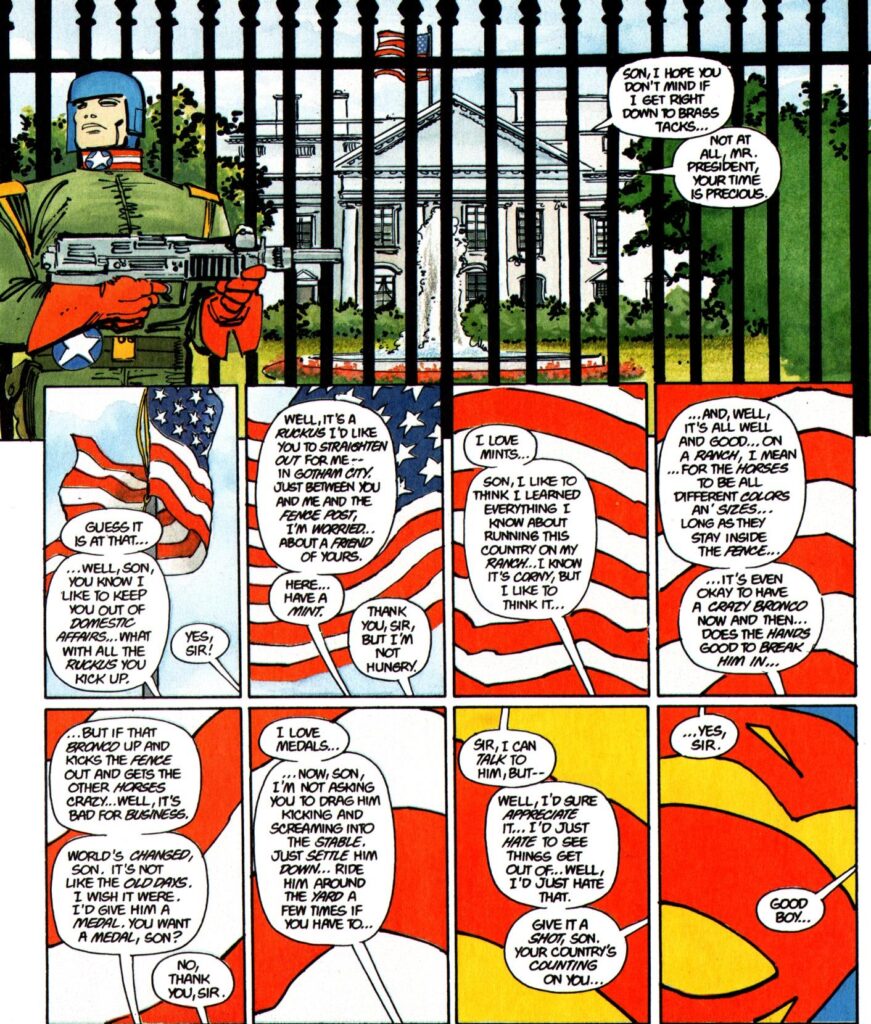

Revealingly, in Superman’s first appearance on that classic mini-series, all we see of him is, precisely, the symbol:

The Dark Knight #2

I’ll point out the obvious: by smoothly transitioning from the US flag to Superman’s costume, this sequence suggests a continuity between the two symbols – a point reinforced by the dialogue, with a subservient Man of Steel (‘your time is precious’) at the direct service of the president (‘I like to keep you out of domestic affairs…’), who considers him a ‘good boy…’

In the story’s world (a then-future DCU), superheroes have been shunned by parents’ groups and by a political sub-committee, allegedly because regular humans felt intimidated by these powerful beings who rose above them. Supes explains the process in terms that would make Ayn Rand proud: ‘the rest of us recognized the danger – of the endless envy of those not blessed.’ He therefore gave his obedience to Washington in exchange for a license to continue to save lives, invisible to the media.

From the start, then, Superman represents the power of the state, enforcing the will of the US president (unnamed, but clearly Ronald Reagan, as evinced already here by the way he disguises authoritarian ticks through a folksy, cowboy-allusive rhetoric). It is heavily implied that Superman even helped hunt down and imprison the heroes who resisted the new status quo (including by amputating Green Arrow’s arm!).

The notion that the Man of Steel is essentially a manifestation of an abstract entity (in this case, state power) is reinforced by the fact that, initially, Superman – much like Batman himself – is not shown, but merely suggested. Diegeticaly, this makes sense because, as mentioned, Supes has become a secret government operative, so he’s meant to act without being seen… But it’s also a way for Miller to tease us, drawing on our knowledge of the character’s powers and of the franchise’s signature catchphrases to build up our anticipation.

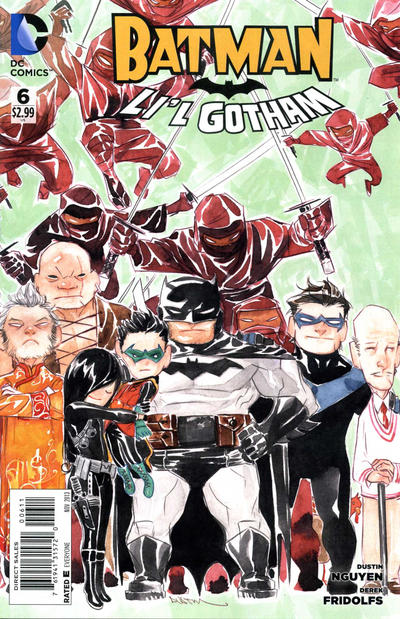

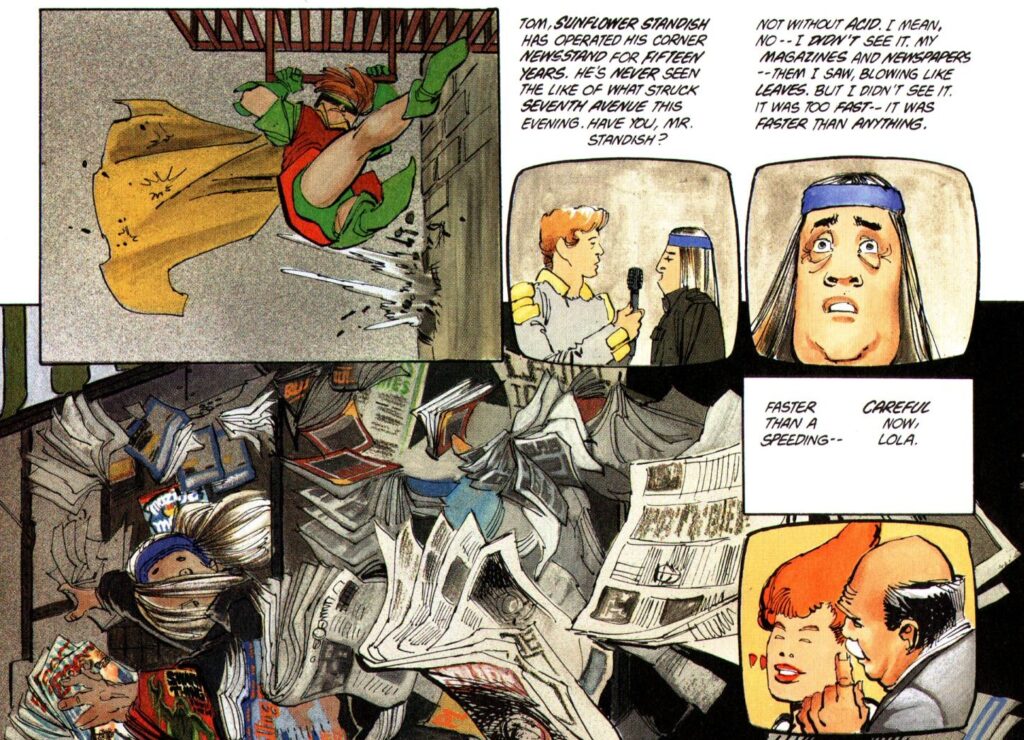

The Dark Knight #3

I guess it’s also Frank Miller showing off his technical prowess, as he keeps coming up with inventive ways of insinuating Superman’s presence: a beam of blue light, an unseen barrier stopping bullets, an ellipse preceding a twisted metal pipe and a burned-up machine gun…

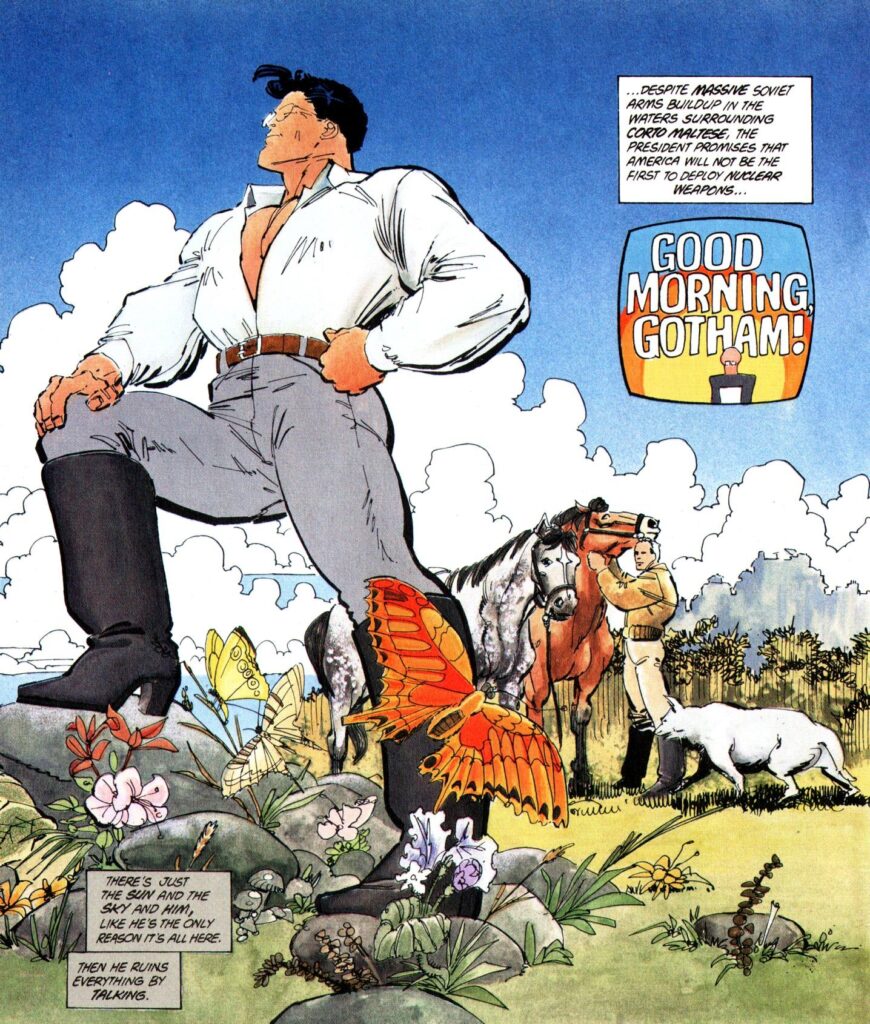

When Superman does fully show up, as Clark Kent, he comes off as a telluric Adonis, embodying not only the US government but the Earth’s life force as a whole. Not only is he framed from a low angle (which makes him look strong and heroic), but it looks like nature is sprouting around him, as underscored by Batman’s narration:

The Dark Knight #3

The character’s magical aura and godlike qualities are reinforced by the way Frank Miller plays with Superman’s iconicity. It’s not just that we recognize his costume or the references to the famous opening of the 1940 radio show The Adventures of Superman. It’s that Miller weaves in all these intertextual nods to convey the sense that the Man of Steel really is the stuff of legends – a kind of mythological figure deserving of awe.

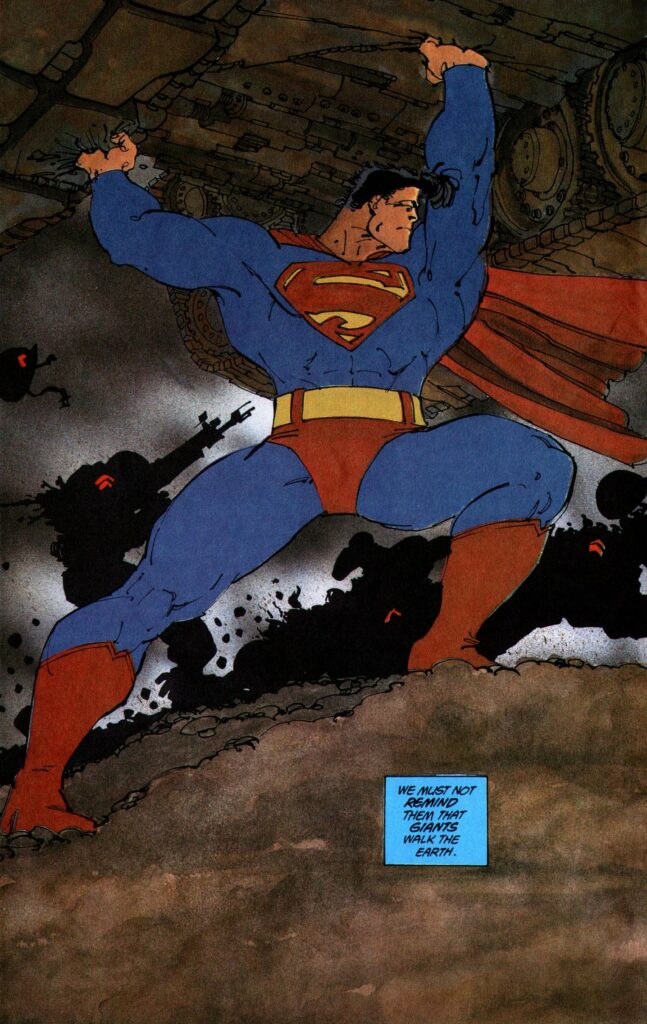

This culminates in the first full-page splash showing readers a clearly visible Superman (no more hints, no more silhouettes), which evokes the cover of the character’s very first issue, 1937’s Action Comics #1… but, instead of a car, now Supes is lifting up a damn tank!

The Dark Knight #3

The fourth issue of DKR brings together all these symbolic dimensions (Reaganite policy, earthly elemental, cultural icon) in two unforgettable sequences.

The first one is the follow-up to the scene you see above, where Superman – ordered by the president – fights off the Soviets from the island of Corto Maltese. In retaliation, the USSR launches an advanced nuclear warhead, which the Man of Steel manages to divert to a desert, where the detonation seriously fucks him up. As argued here, in just a few pages Superman thus simultaneously allegorizes the US military machine (and foreign intervention), Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (and its limitations), and the environmental collapse derived from nuclear war… And all of this is made particularly forceful by the contrast between the iconic Superman (shown above) and the disfigured creature practically destroyed by the atomic blast (which I’ll revisit in an upcoming post).

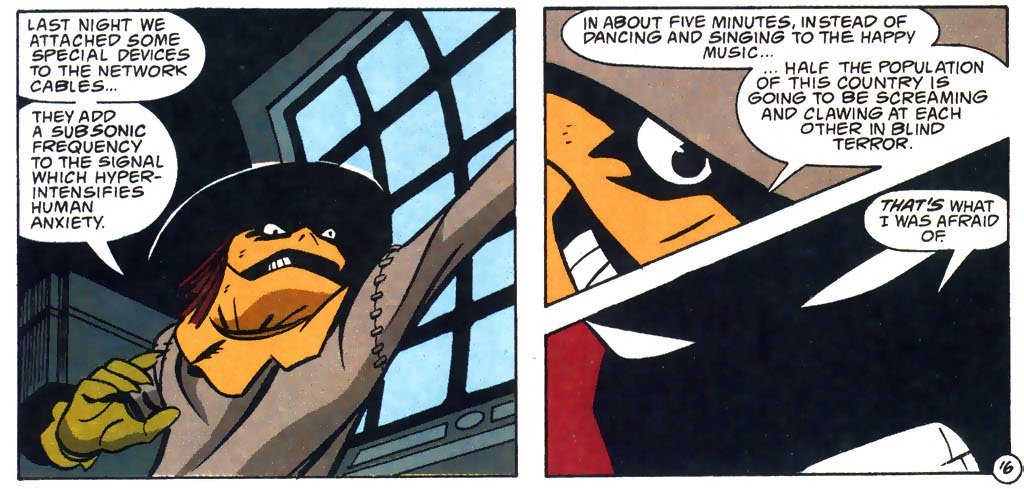

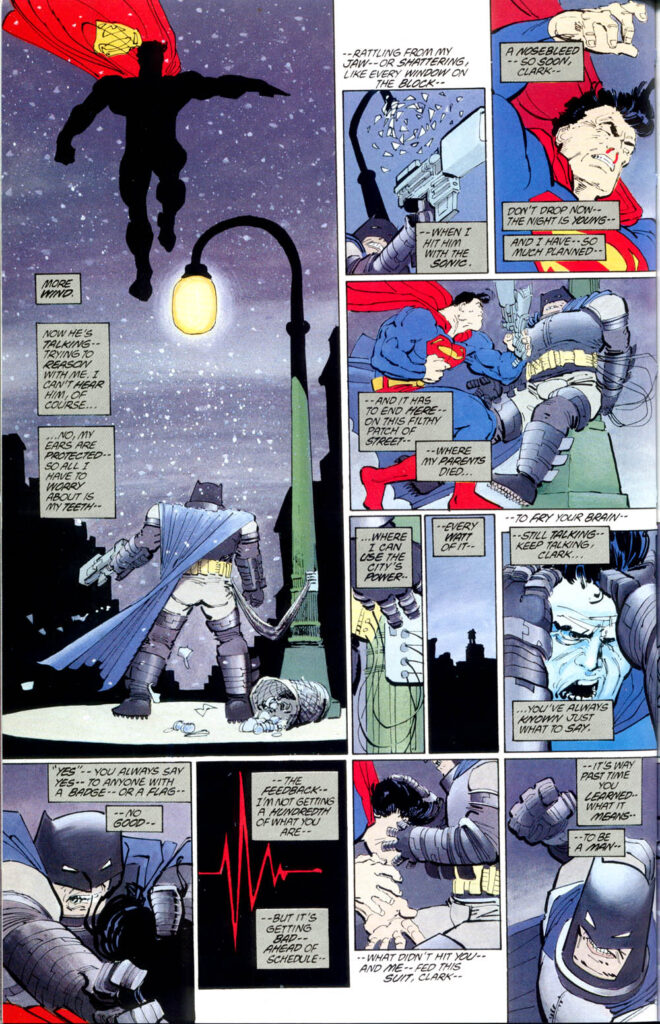

But it’s the other sequence that would turn out to be the most influential: the ultimate fight between the Man of Steel and the Dark Knight, which inspired countless riffs over the years (on the pages and on the screen). Because this was Batman’s book, the deck was stacked against Superman – and, indeed, in part the fight served to show off the awesomeness of a courageous, resourceful, defiant human going up against a god…

The Dark Knight #4

As stressed by Batman’s words, at the end of the day Superman didn’t represent divine power as much as he represented the federal government, especially since the very reason he fought the Dark Knight was because the latter refused to bow down to the authorities. In other words, in order to make Batman a libertarian underdog, Frank Miller ended up reducing Supes to a mere stooge.

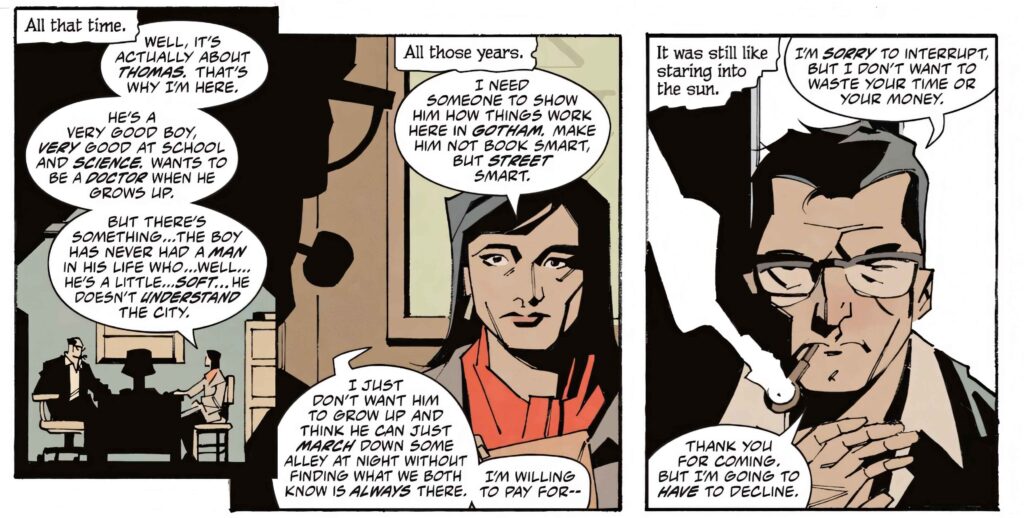

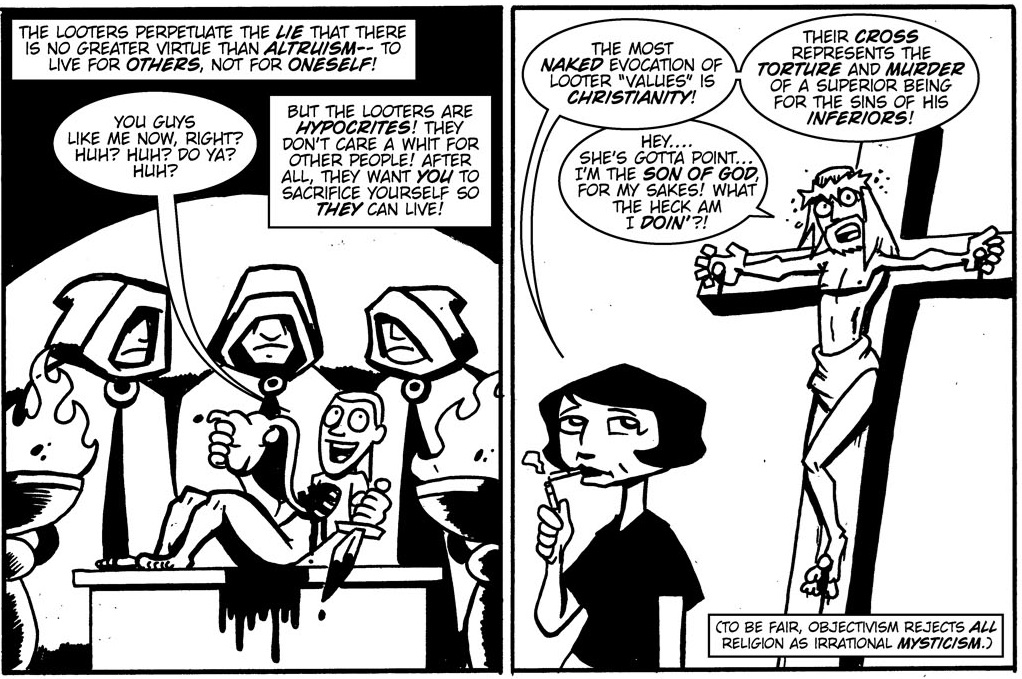

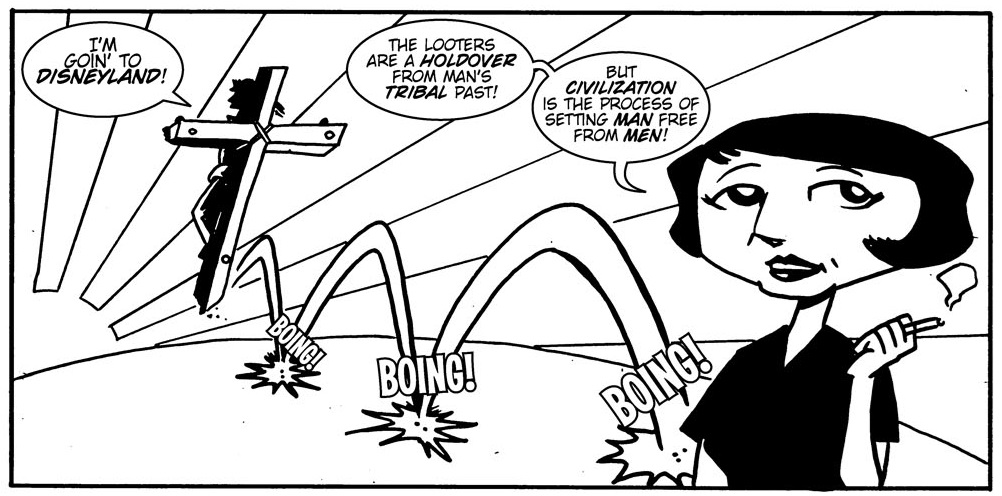

A big part of the vilification of Superman entailed the charge that, by agreeing to remain invisible and bowing down to the government, he was undermining Randian ideals, which brings us back to objectivism… According to this philosophical system – which Miller has acknowledged as a major influence – the highest moral purpose in life is to enjoy one’s own productive achievements, as opposed to conforming and compromising to the oppressive hostility of the ‘looters’ who want you to sacrifice for society’s good (here seen as the good of undeserving weaklings who exploit the genius of the strong).

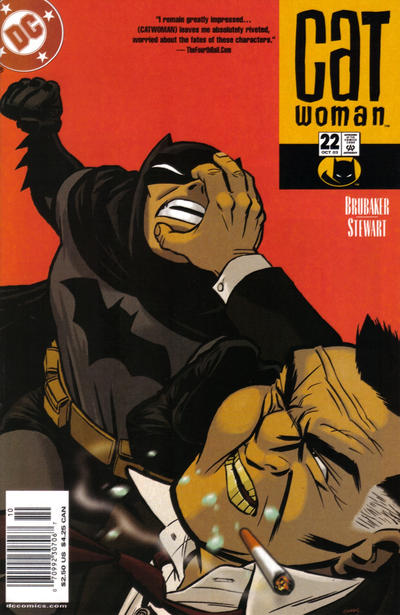

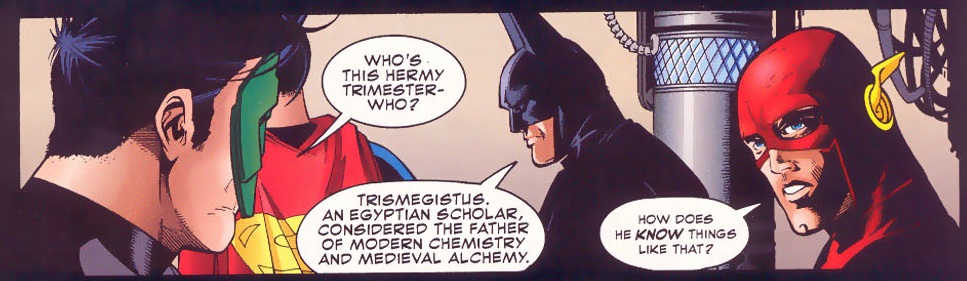

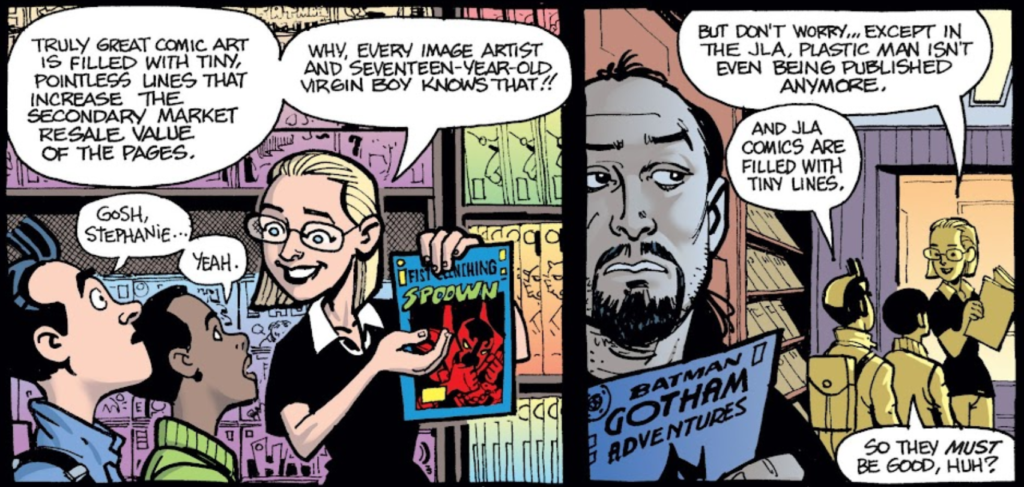

I’m going to let Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey explain it better:

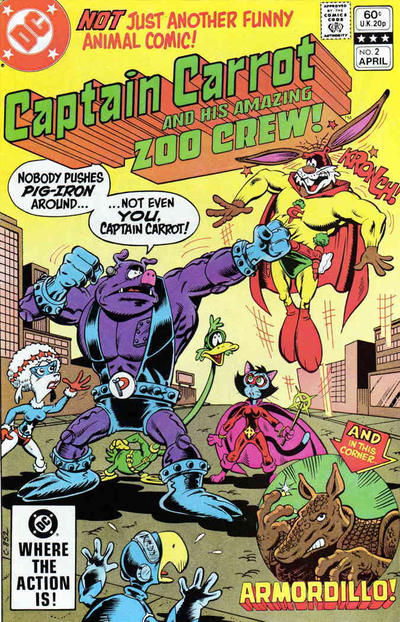

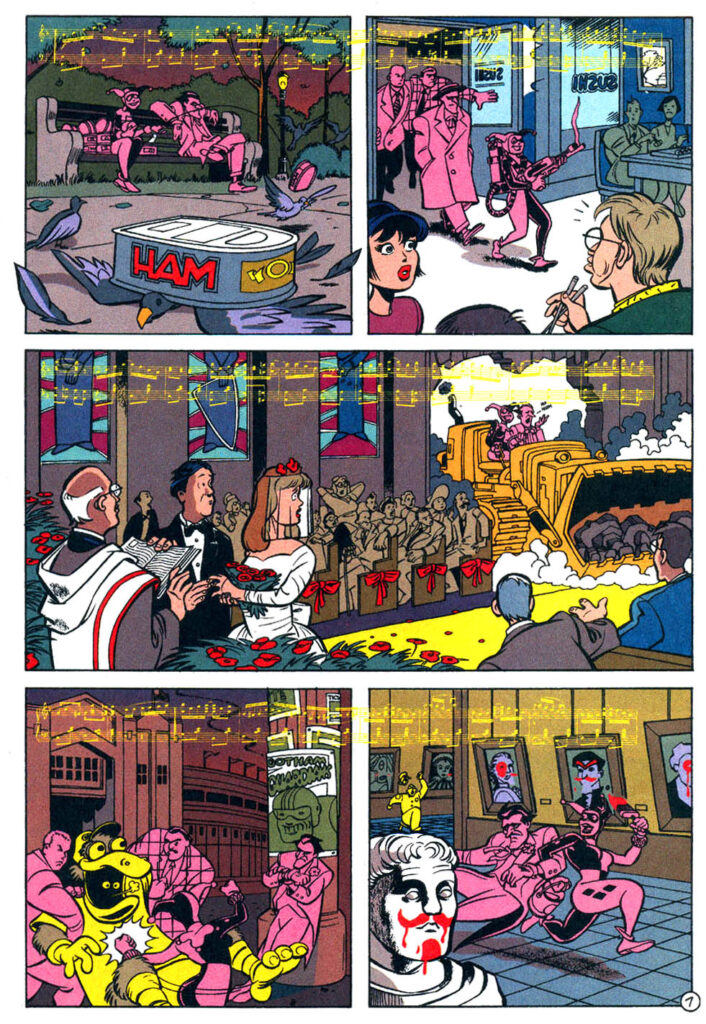

Action Philosophers! #2

You can hear Ayn Rand’s whisper when the Caped Crusader, speaking for the true heroes, condemns the Man of Steel for giving in to the looters: ‘You sold us out, Clark. You gave them – the power – that should have been ours.’ Later, Batman adds: ‘I’ve become a political liability… and you… you’re a joke…’

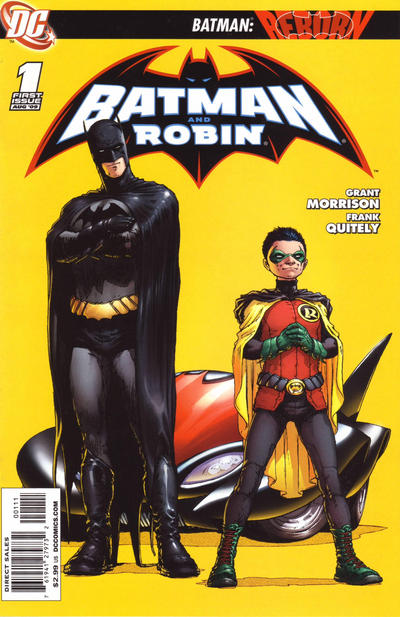

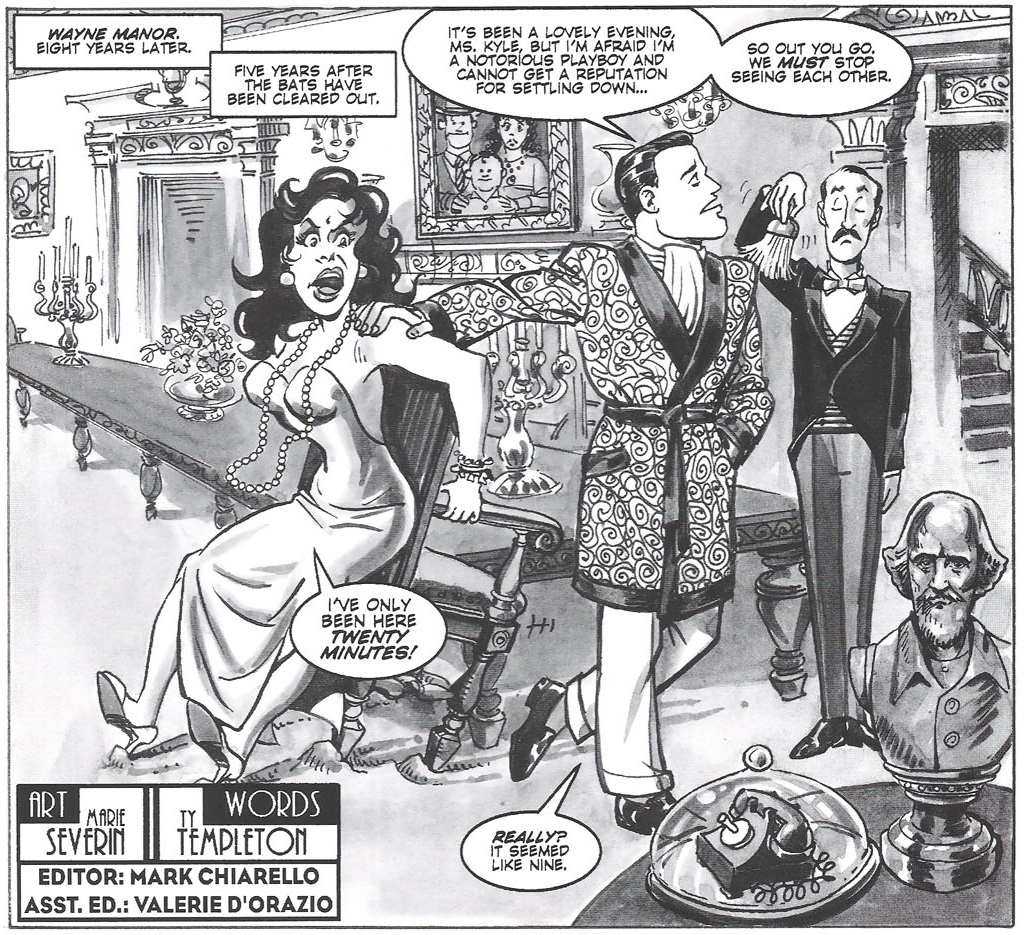

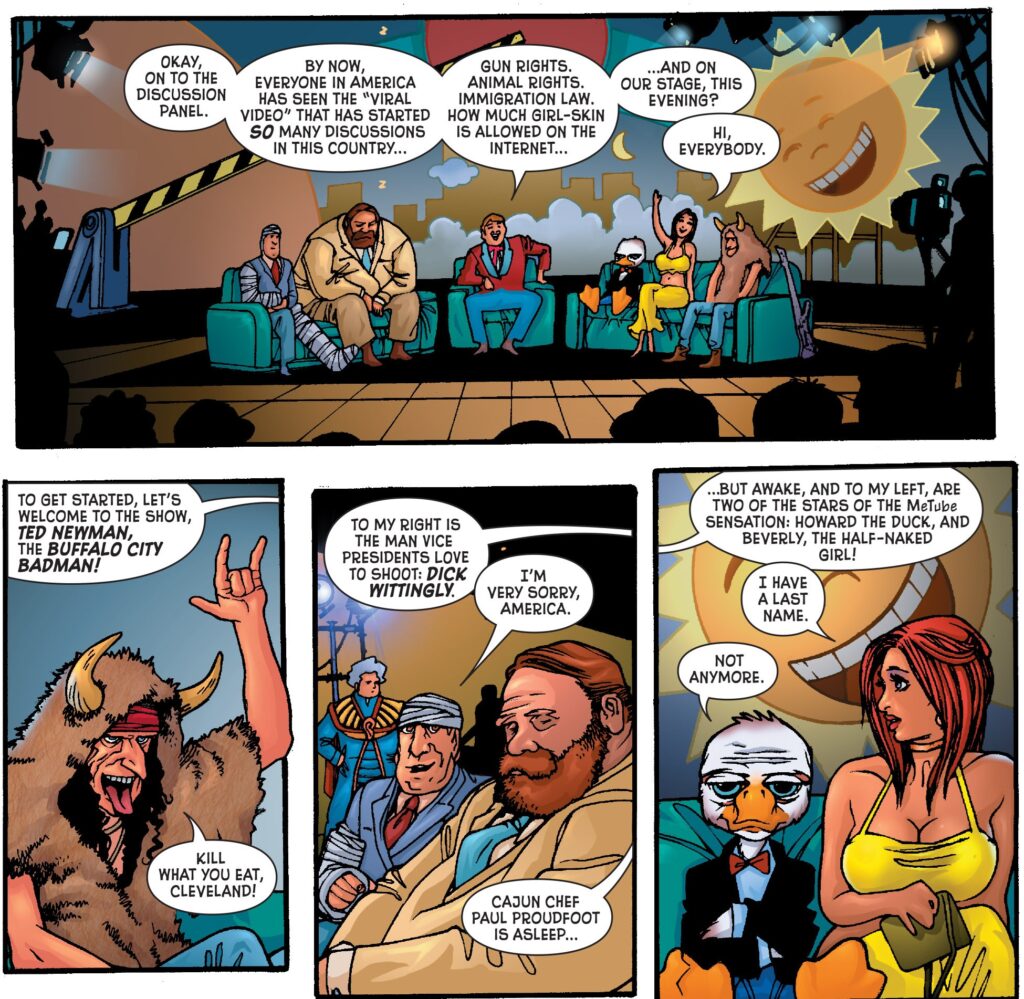

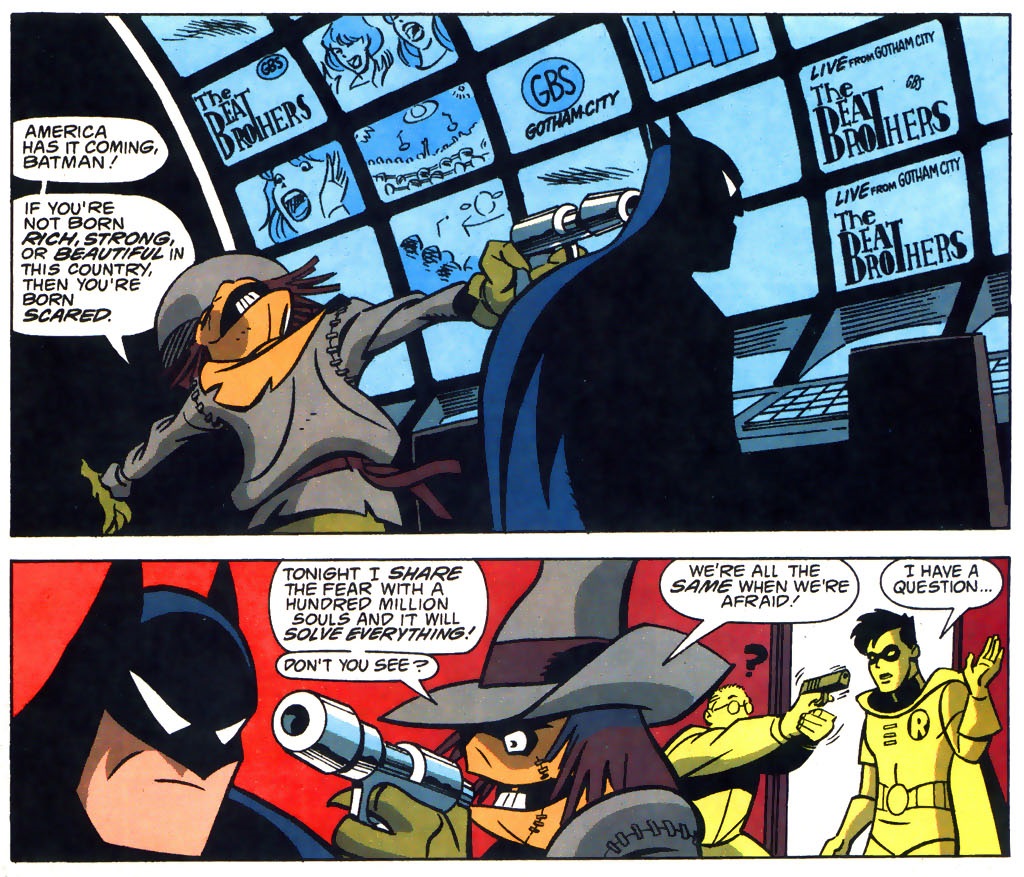

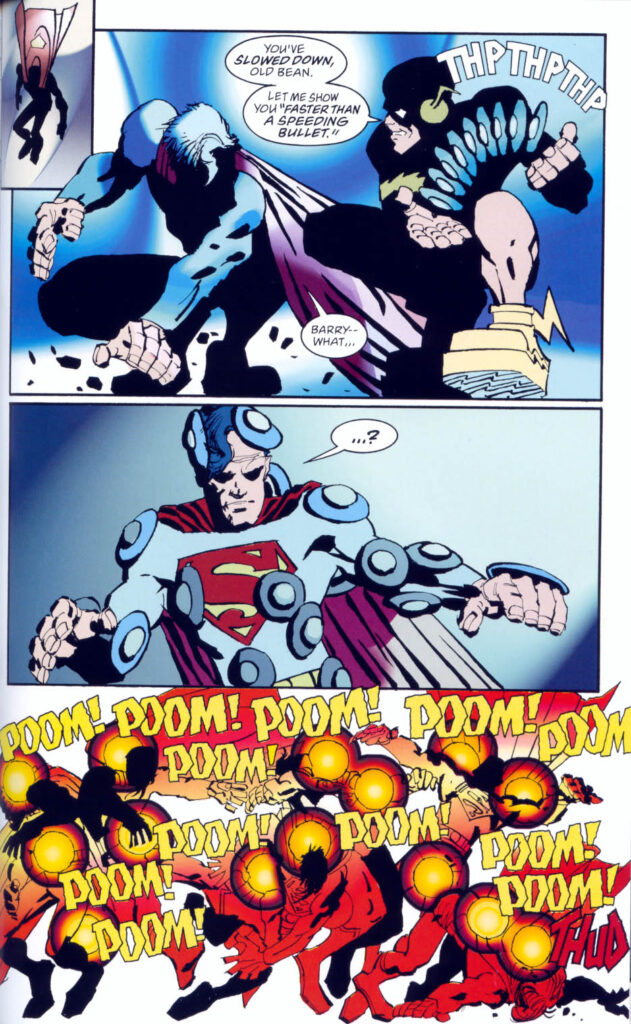

He’s not wrong. DKR’s Superman is a joke, in the sense that there is something amusingly iconoclastic and subversive (at least at the time) about beating up such a respected boy scout figure. Miller then expanded the joke in 2001’s sequel, The Dark Knight Strikes Again, where the Man of Steel now got humiliated both by the villains (Lex Luthor and Brainiac blackmail him by holding the Bottle City of Kandor hostage) and by other heroes:

The Dark Knight Strikes Again #1

You can also sense Frank Miller having a naughty, irreverent laugh when he depicts Superman impregnating Wonder Woman as they have aerial sex and then fall into the ocean, causing a tsunami, a volcano eruption, and a massive hurricane (‘The Pentagon denies any thermonuclear deployment’). It’s an incredible, visually arresting sequence whose impact derives, in large part, from the fact that it flies against the character’s wholesome connotation. (You can find a more elegant version of this scene in ‘The View from Above,’ from Astro City (v3) #7.)

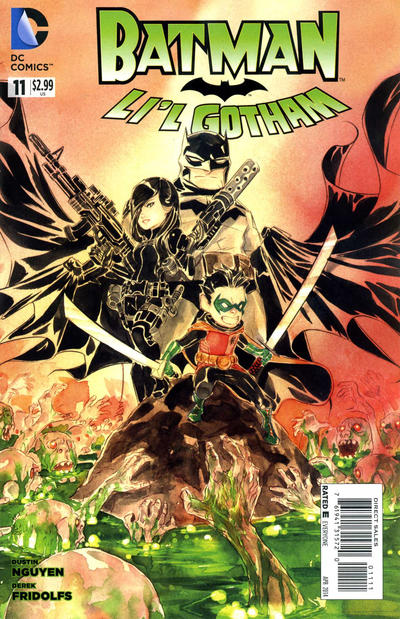

As the New York-based Miller was working on The Dark Knight Strikes Again, however, the 9/11 attacks happened. This had a profound effect on him, resonating in Miller’s comics – and in his public statements – for years to come. One of the first things he did was to use Superman and his beloved cast to render gravitas to a potent tribute on the pages of the series’ final issue, where a Metropolis devastated by an alien monster blatantly stands in for the ruins of the World Trade Centre:

The Dark Knight Strikes Again #3

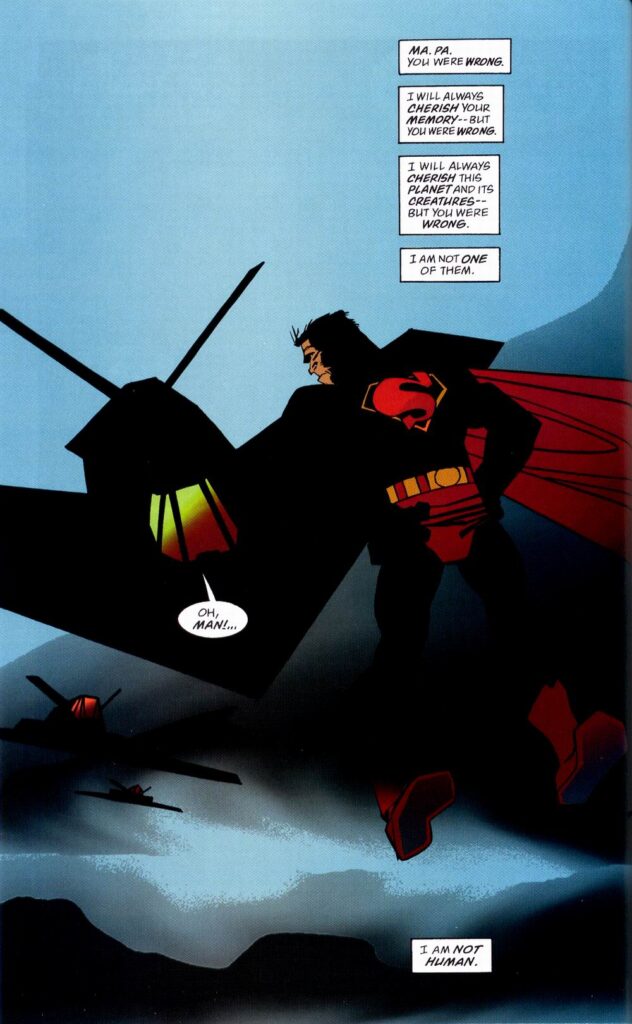

Notice how the Man of Steel now looks like Sin City’s Marv, albeit with laser-red eyes highlighting his rage. Indeed, these events, along with the influence of his daughter Lara (that’s the creepy girl you see hovering on the pages above), pave the way for Superman to become much more assertive, unashamedly embracing his power while crying out for revenge.

Rather than accepting it as a mere character arc, this shift can be read by taking into consideration Superman’s wider history, namely his association with the so-called ‘American Way.’ As he raises himself above humanity, then, the Man of Steel appears to be embodying a chauvinistic post-9/11 discourse about the USA aggressively reaffirming its superpower status above other nations…

The Dark Knight Strikes Again #3

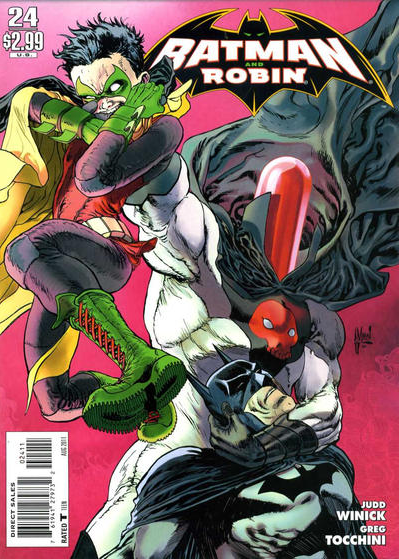

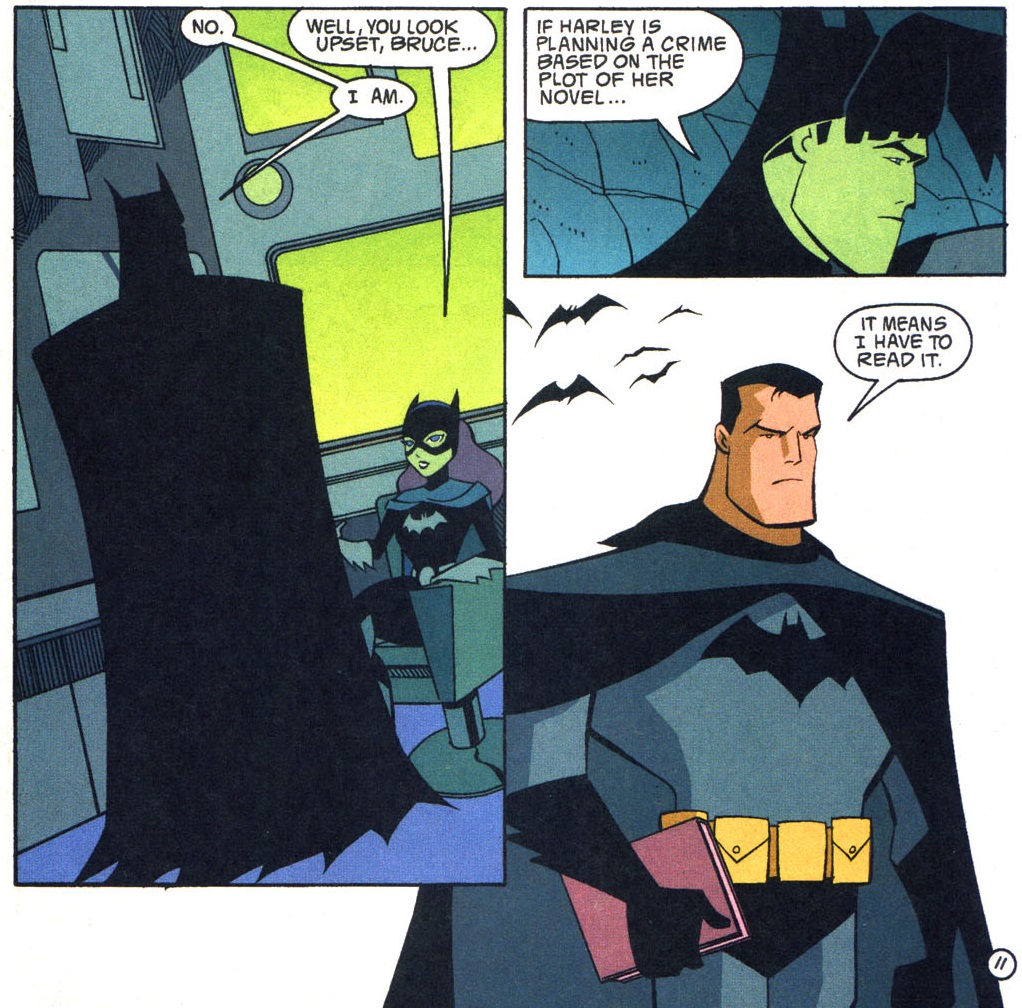

To be fair, Frank Miller eventually addressed the fascistic implications of this transformation. Twelve years later, he co-wrote with Brian Azzarello a third installment of the Dark Knight saga, suitably titled The Master Race, which now used Superman as a vehicle to confront the rise of the far right (a topic that became even more relevant throughout the series’ publication, from 2015 to 2017).

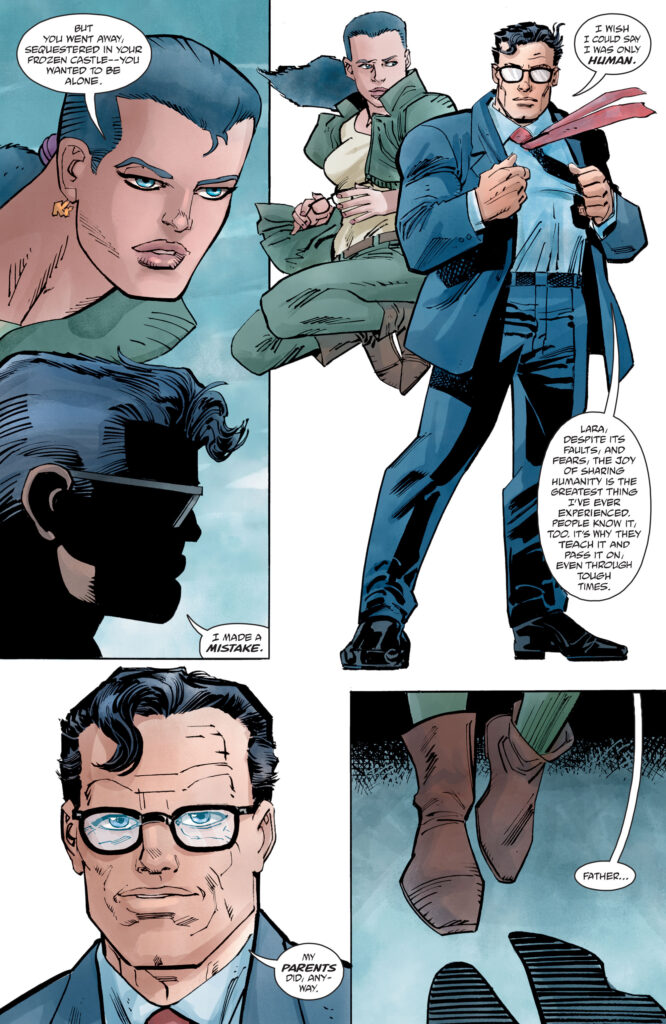

The premise of The Master Race was that Lara, who despised her father’s submissive attitude (‘Why did you let the ants knock you from the sky?’), managed to restore the inhabitants of Kandor to full-size (because ‘they’re tired of being small’) – but this time we got to see the dark side of such an ideological stance, as Kryptonian supremacists proceeded to terrorize and enslave humanity.

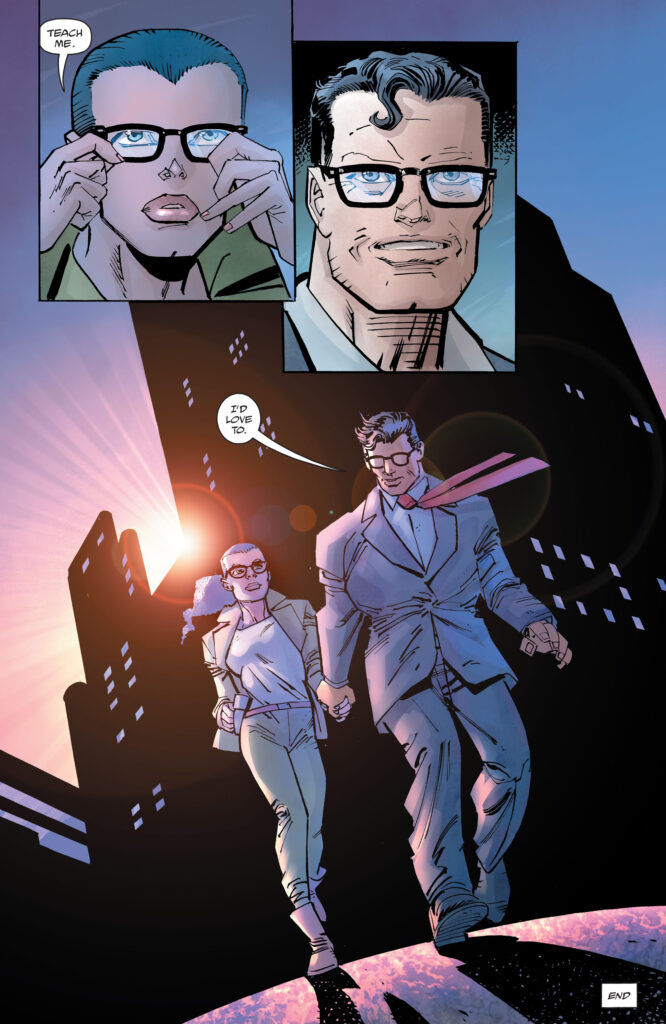

And so, for once, these comics actually endorsed Superman’s humanism. Rather than a foe, the Man of Steel was now treated as Batman’s ally in the resistance against Kryptonian tyranny. Hell, the series actually finished with an inspirational monologue in which Superman praised humility, altruism, and solidarity, teaching his daughter that, rather than proudly tower above regular people, they should admire and learn from them. At the very end, Clark Kent’s glasses thus became an anti-Trump metaphor:

The Master Race #9

In a couple of weeks, we’ll see how Miller, having explored the symbolic potential of the Man of Steel, also dug into his personality, in Superman: Year One.