As an embodiment of changing fads and obsessions of US pop culture, Batman’s adventures could hardly stay immune to the social impact of the Vietnam War. And while the Caped Crusader’s TV incarnation could initially be seen advertising war bonds, the comic books went on to plaster Gotham City with several reminders of the physical and psychological toll of that conflict.

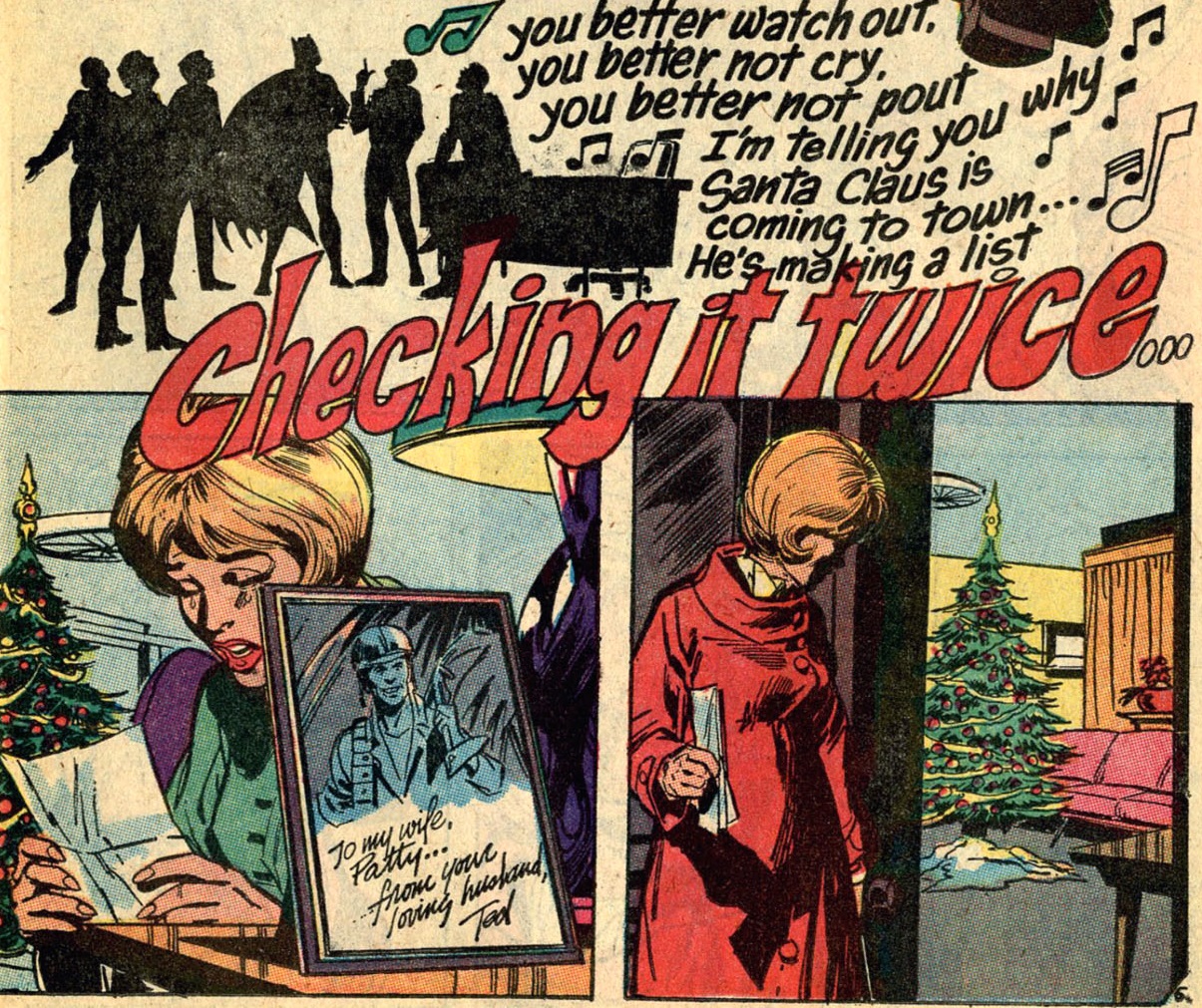

This goes back to the war era itself. In the classic ‘The Silent Night of the Batman’ (cover-dated February 1970, written by Mike Friedrich, with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano), we briefly meet a woman who seems desperate about her husband fighting abroad…

Batman #219

Batman #219

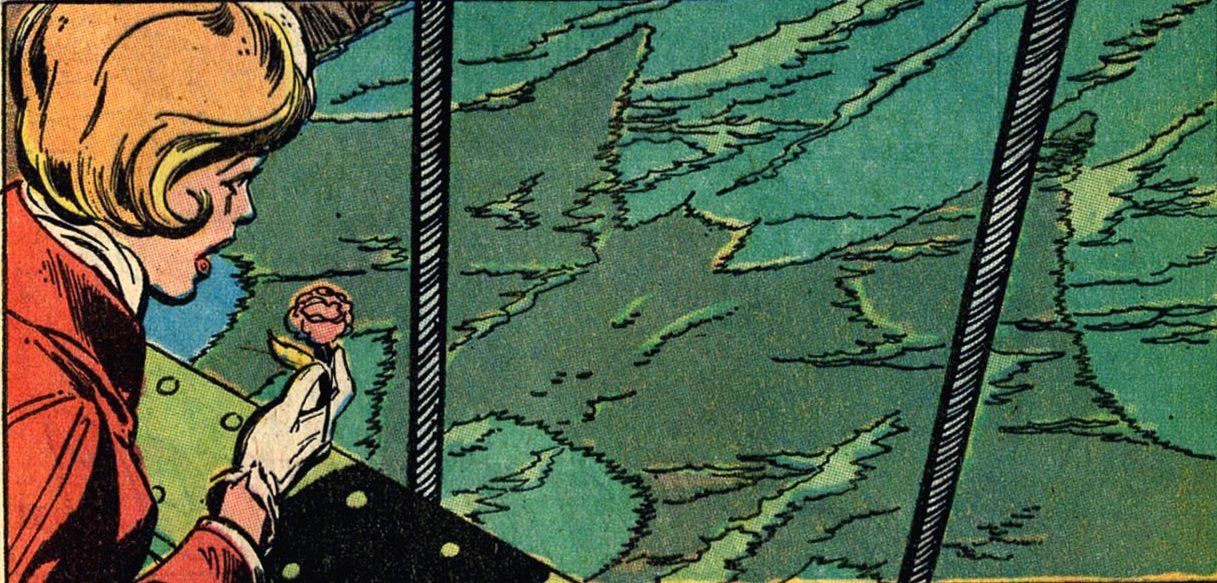

While crying at the edge of a Gotham bridge, she looks at the water and appears to gain a new sense of hope as she notices the shape of the bridge’s shadow:

Batman #219

Batman #219

It’s such a powerful image. Darn it if Adams doesn’t seamlessly pull off the parallel between the shadow and the bat-symbol… It reminds us that this symbol can be an inspiration for average citizens as much as it can be a source of terror for the foes of the Dark Knight.

Two issues later, Mike Friedrich briefly returned to the topic in ‘Hot Time in Gotham Town Tonight!,’ which revolved around an African-American soldier who brought back an idol from Vietnam with an evil demon trapped inside (subtle, I know). Friedrich was 20-years-old at the time and this problem was clearly on his mind. As I mentioned before, he also wrote ‘The Private War of Johnny Dune!,’ in which Batman and the rest of the Justice League of America faced a disgruntled vet who used his hypnotic voice to mobilize the youth to march against the power!

Frank Robbins, who was well into his fifties, engaged with the conflict’s impact in his own eccentric way by creating a couple of very different recurring characters: Jason Bard, a private detective who walked around with a cane because of a crippling injury sustained in Vietnam, and Philip Reardon, a blind villain who had his optic nerves reconnected into his fingertips and called himself the Ten-Eyed-Man.

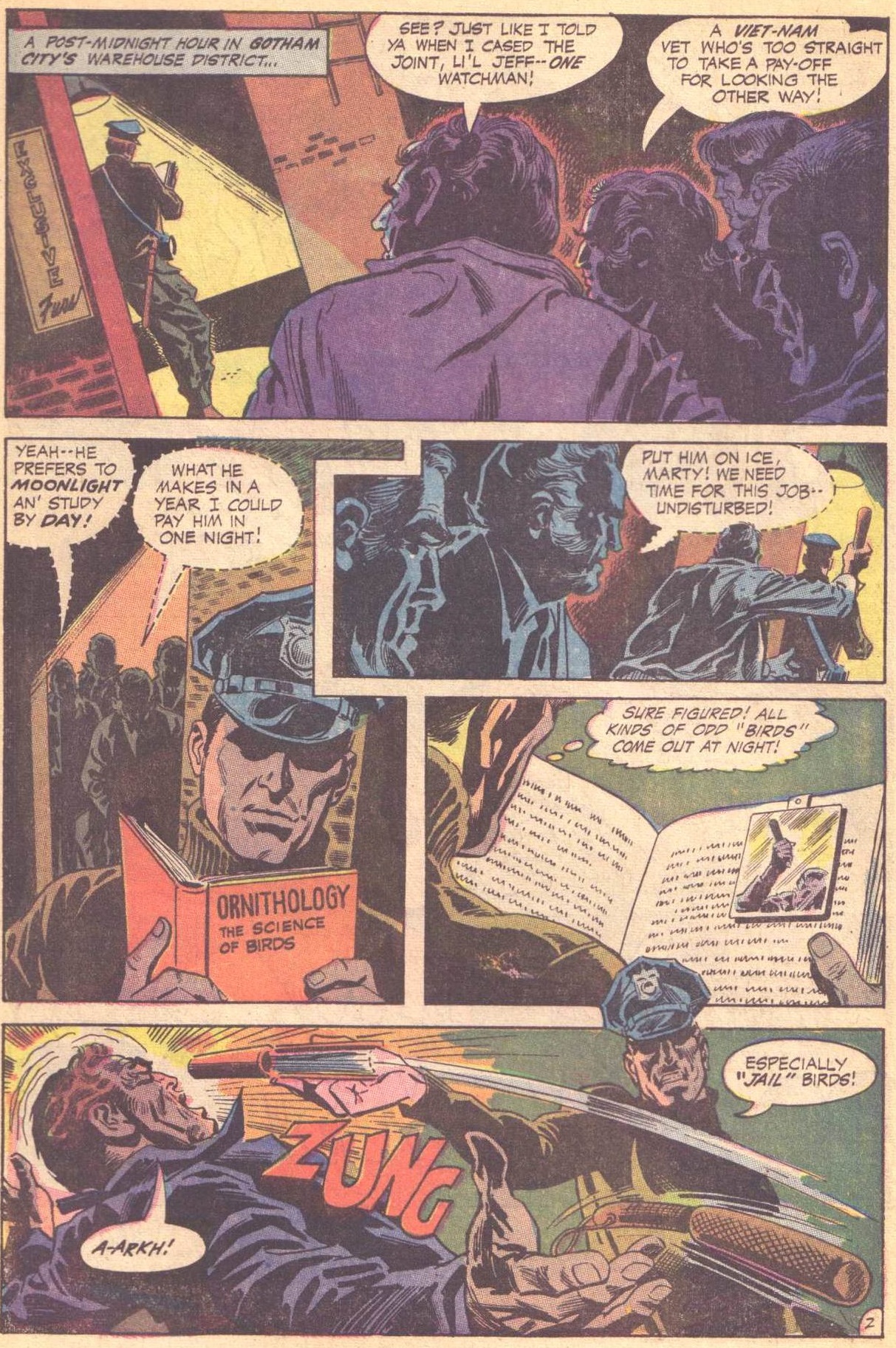

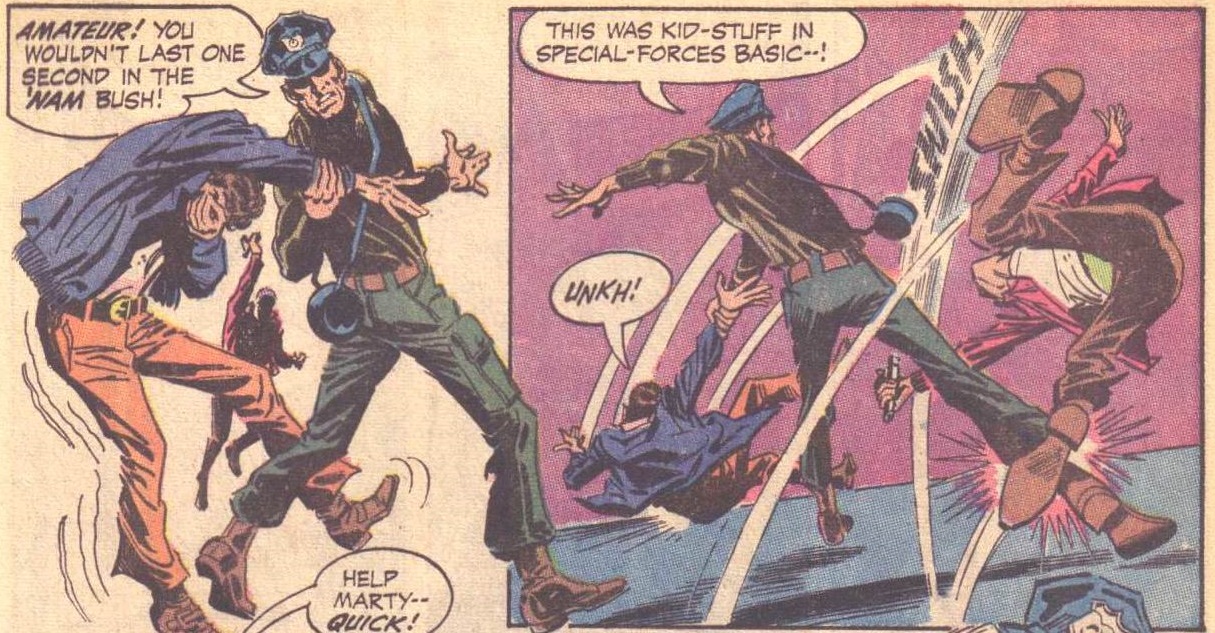

The latter actually started out well enough… Before going blind, Reardon was established as an efficient veteran of the Special Forces who knew how to keep an eye out for danger by making use of unexpected angles:

Batman #226

Batman #226

In another neat bit of foreshadowing, we learned that during the war an enemy grenade fragment had lodged itself onto his forehead, earning him the nickname of ‘Three-Eye’ Reardon. Soon, however, Philip Reardon’s saga spiraled out of control… He lost his sight in a blast, blamed Batman for it, and – equipped with his freaky fingertip vision – set out for vengeance.

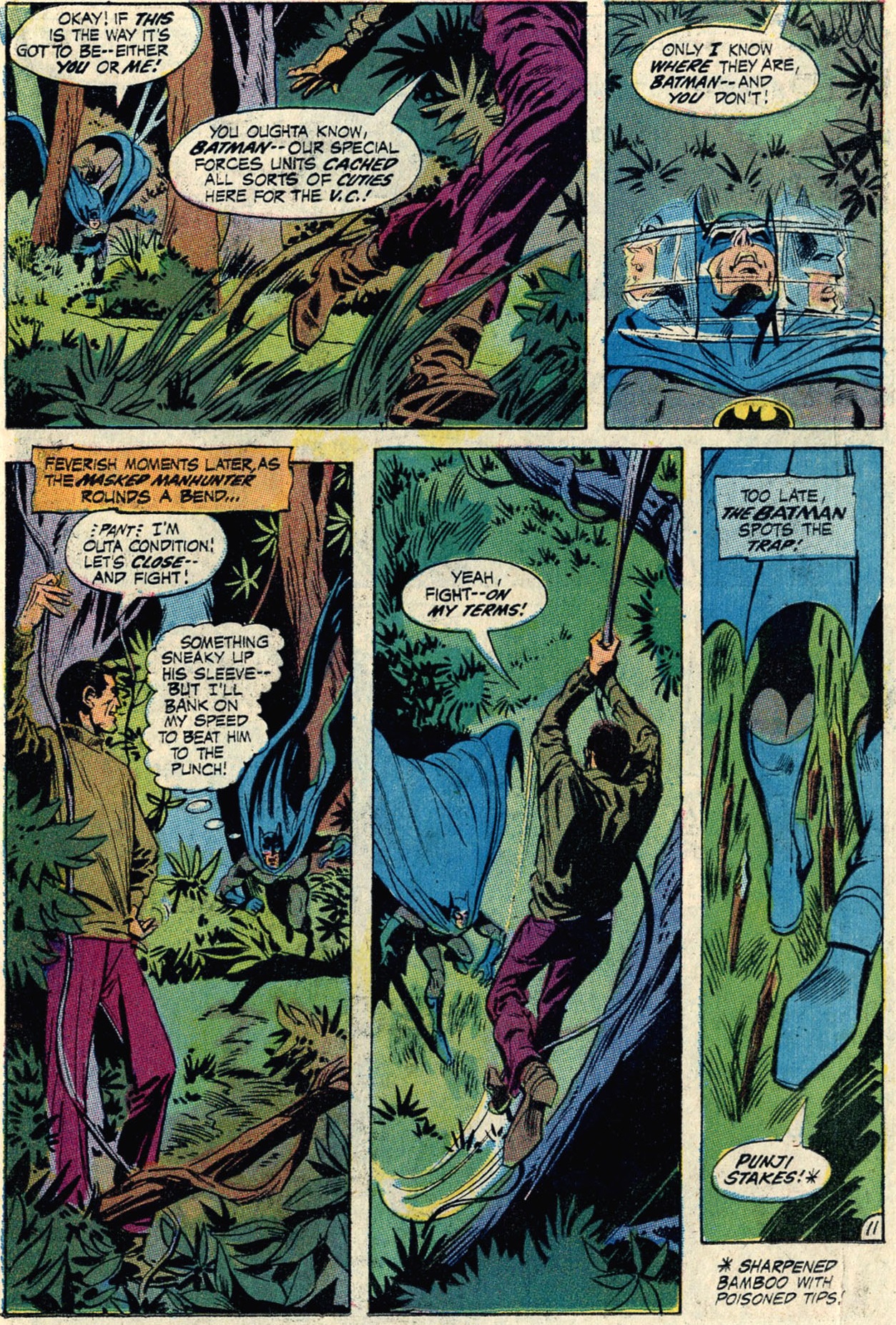

His most elaborate revenge scheme involved hijacking a goddamn airplane and convincing the White House to exchange the Caped Crusader for the hostages, so that Reardon could fight Batman on his turf, i.e. the Vietnamese DMZ:

Batman #231

Batman #231

As plans go, it is a particularly outlandish one, even for the standards of Batman’s rogues’ gallery. However, as a result, this issue – published in early 1971 – can be seen as somewhat demystifying the allure of combat in an era when kids were still being shipped out to the jungle… In a roundabout way, the comic called attention to the brutal violence of the weapons being used on the ground (like the ‘bouncing betty,’ described as ‘a devilish land-mine used by the Cong’).

It also heavily implied that the reason the Ten-Eyed-Man had come up with such a kooky scheme in the first place was because he had not returned from the war without a degree of PTSD…

Batman #231

Batman #231

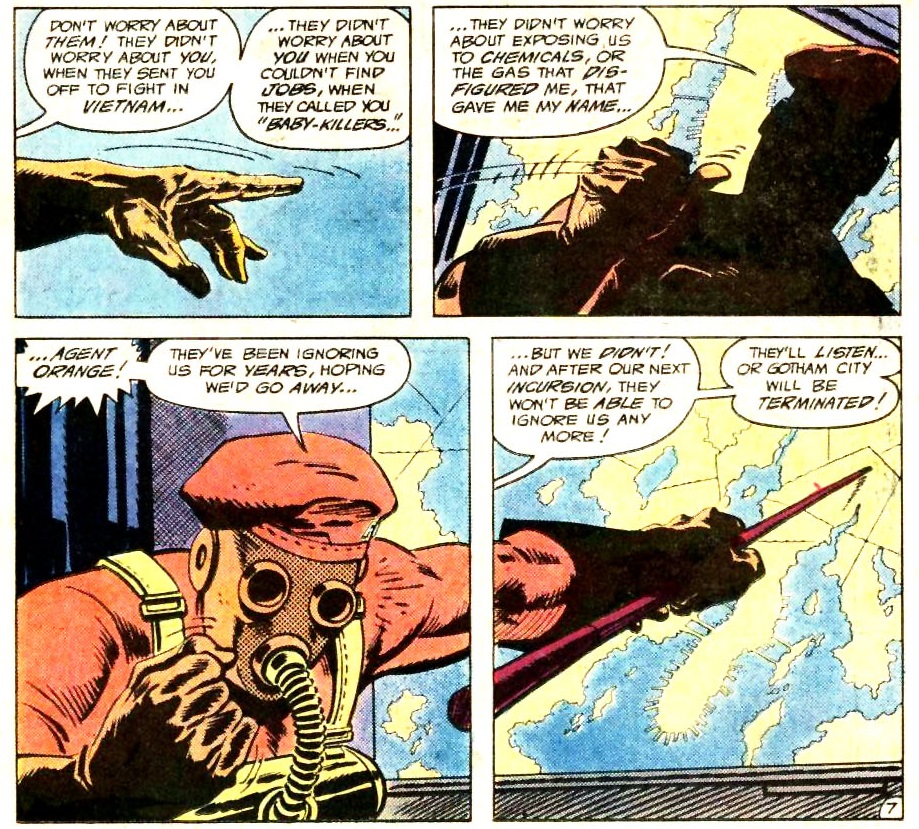

Now, there have been many great works written about the trauma and the challenges of coming back from the war and the soldiers’ difficulty in reintegrating into a society that would rather pretend they didn’t exist, but leave it to Batman comics to assign these problems to the oddest characters. When Mike W. Barr and Jim Aparo tackled the topic on the pages of Batman and the Outsiders, instead of the angst-ridden John Rambo of First Blood or even the desensitized Frank Castle of Marvel’s Punisher fame, we got this dude:

Batman and the Outsiders #3

Batman and the Outsiders #3

(The best part is that he wasn’t really disfigured, just looking for a pretext to fight another war…)

In Legends of the Dark Knight #91-93, the king of war comics, Garth Ennis, gave us yet another goofy villain to come out of Vietnam in the form of Doctor Freak, a batshit crazy hippie who sought to get all of Gotham tripping on acid.

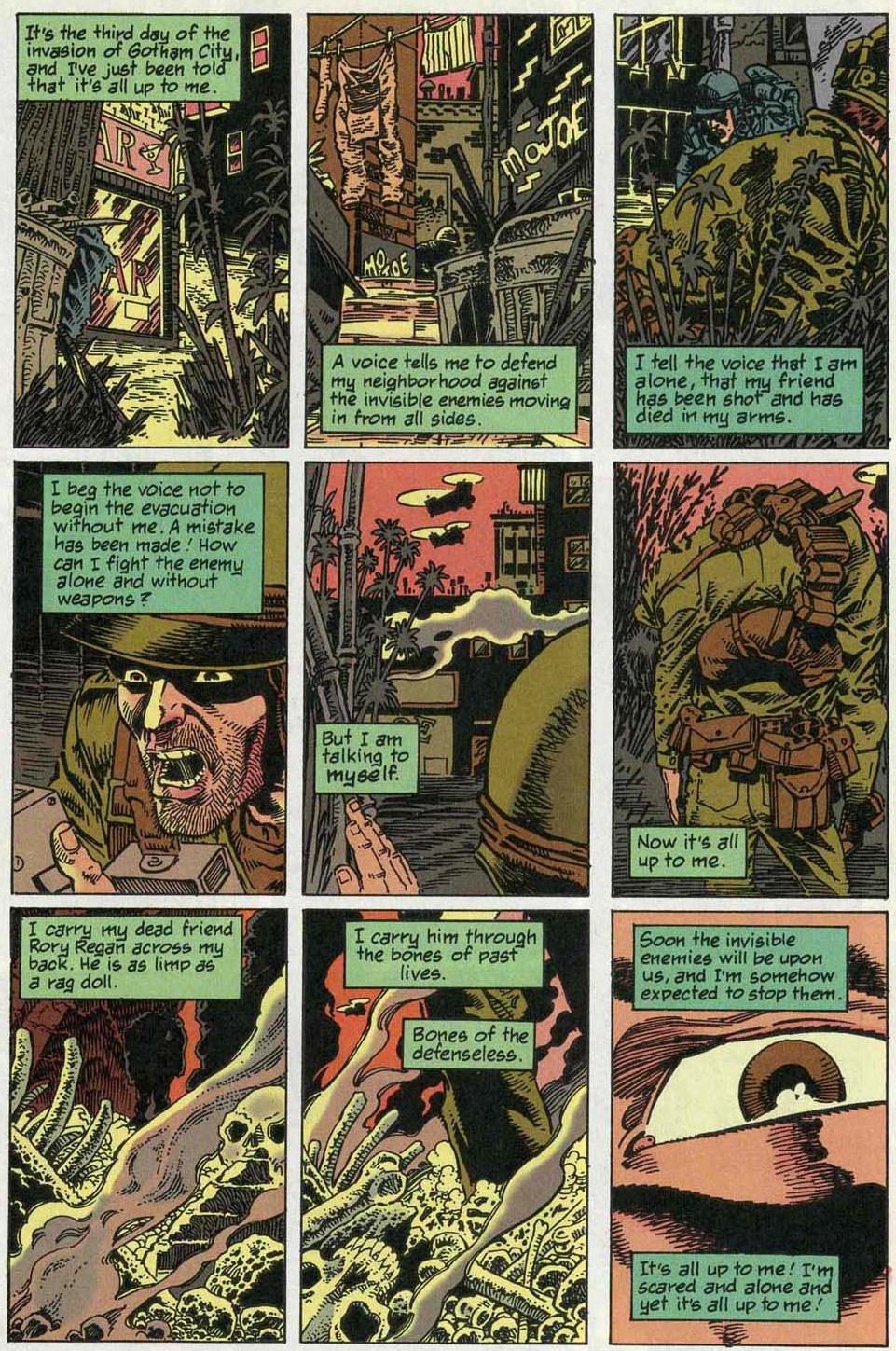

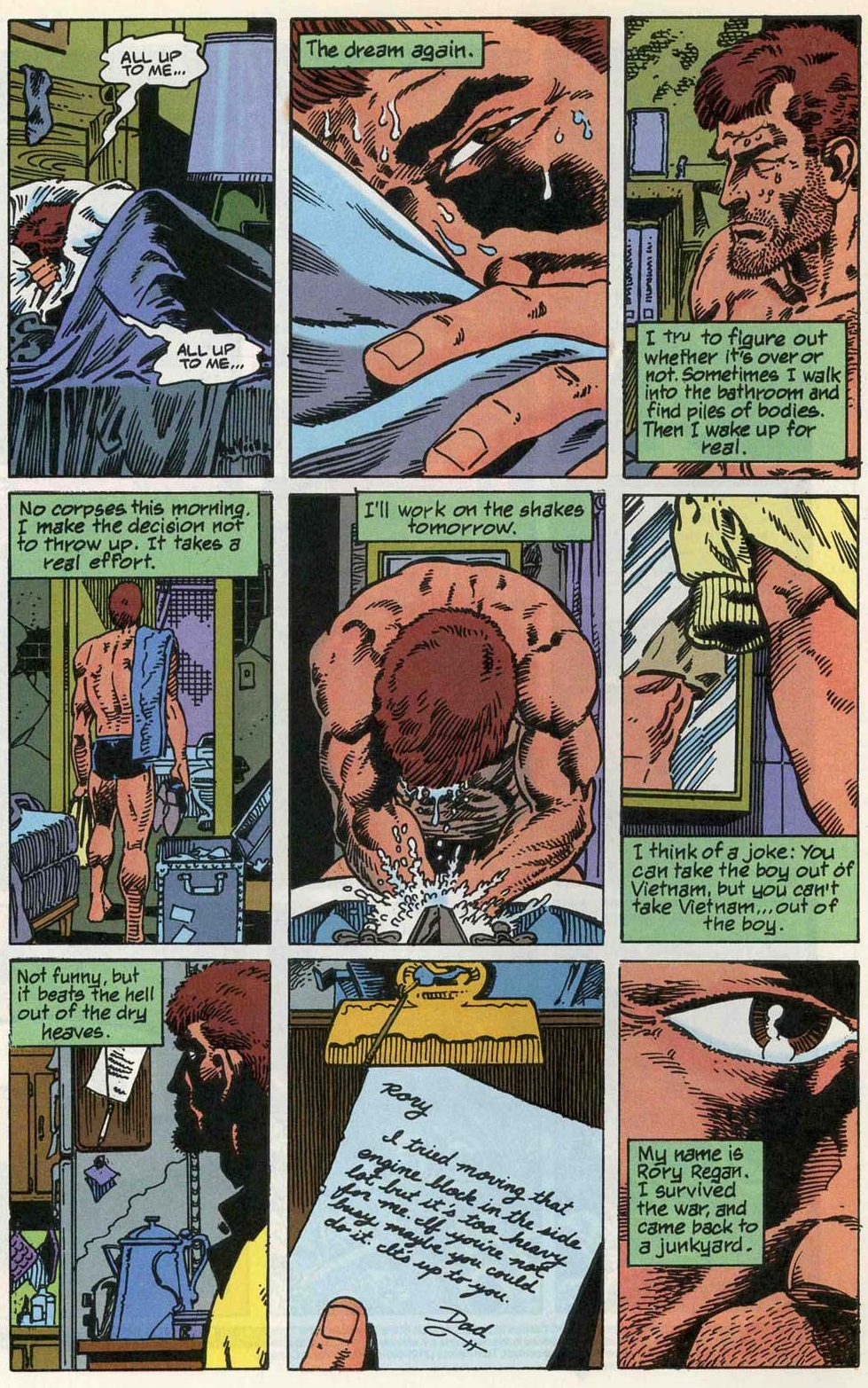

Rory Regan – also known as the Jewish superhero Ragman – is a (relatively) less obscure Gothamite veteran. The impact of Vietnam was not a big deal in his original series (1976-1977), but writers Keith Giffen and Robert Loren Fleming gave it more prominence in the 1991 reboot… This is how they introduced their protagonist on the very first couple of pages:

Ragman (v2) #1

Ragman (v2) #1

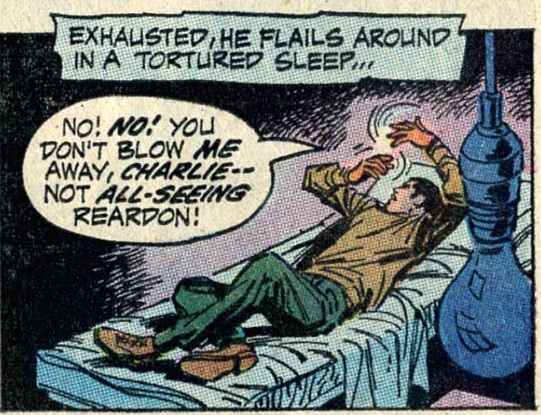

This version of Rory Regan went on to star in the 1993 mini-series Ragman: Cry of the Dead, by Elaine Lee and Gabriel Morrissette. It was a gritty horror comic, set in New Orleans, which revolved around a demon who viciously avenged dead children… That series showed how the Vietnam War continued to haunt Rory’s dreams, drawing a parallel between the abusive parents in the story and the US government, who had drafted innocent kids and then put them through Hell.

That said, I don’t think any writer went farther than Alan Grant in terms of repeatedly conveying to readers that the legacy of this conflict was still around on the streets of Gotham. Always one to wear his politics on his sleeve, Grant kept bringing up the lingering brutality of war in his stories… In Detective Comics #590, a terrorist cell committed a massacre at the ‘Nam Vets’ Club (Commissioner Gordon: ‘It makes me sick to my gut! Those vets have had more than their share of suffering already!’). In Detective Comics #616, Batman tried to stop a demonic sacrifice at Gotham’s War Vet’s hospital. In Shadow of the Bat #6, an ultra-patriot violently lashed out at anti-Vietnam War protesters and ended up being recruited by the CIA, who then somehow amplified his patriotism to even more insane levels through judicious doses of LSD, deep hypnosis, and sensory deprivation. He became a super-jerk, under the codename ‘The Ugly American.’ (And yes, just in case you miss the point, there’s totally a moment when Batman tells a CIA agent: ‘You called him the Ugly American – but the truth is, you and your goons are the real ugly Americans!’)

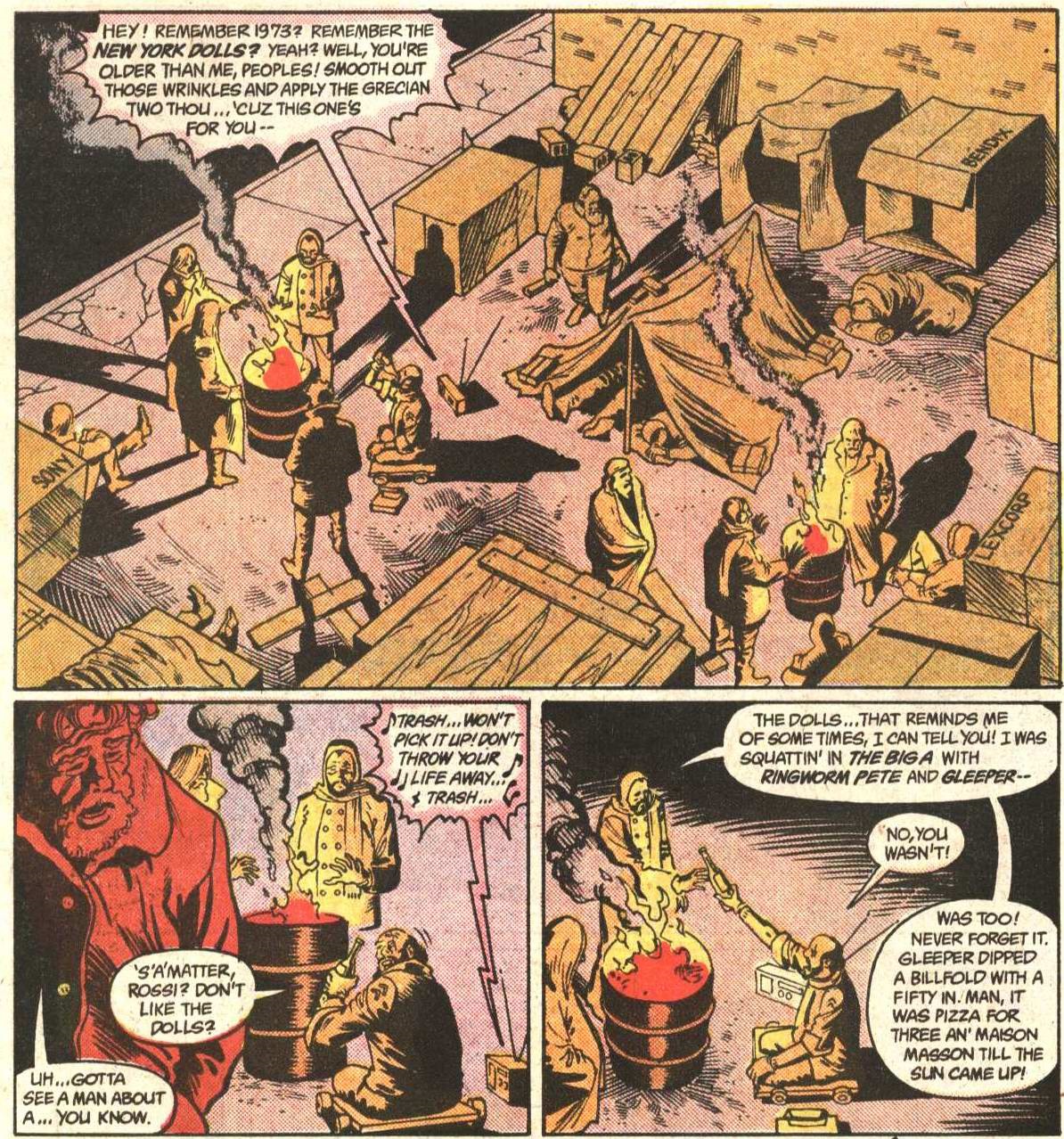

Alan Grant’s most long-lasting contribution – co-created with the brilliant artist Norm Breyfogle – was Legs, an opinionated homeless alcoholic who lost his lower limbs due to an anti-personnel mine in Vietnam (or as he put it: ‘I didn’t lose ‘em… I know exactly where they are… Spread over twenty meters of the Mekong Delta!’). Legs made his debut in the awesome three-part arc ‘Night People’ (Detective Comics #587-589), back in 1988:

Detective Comics #587

Detective Comics #587

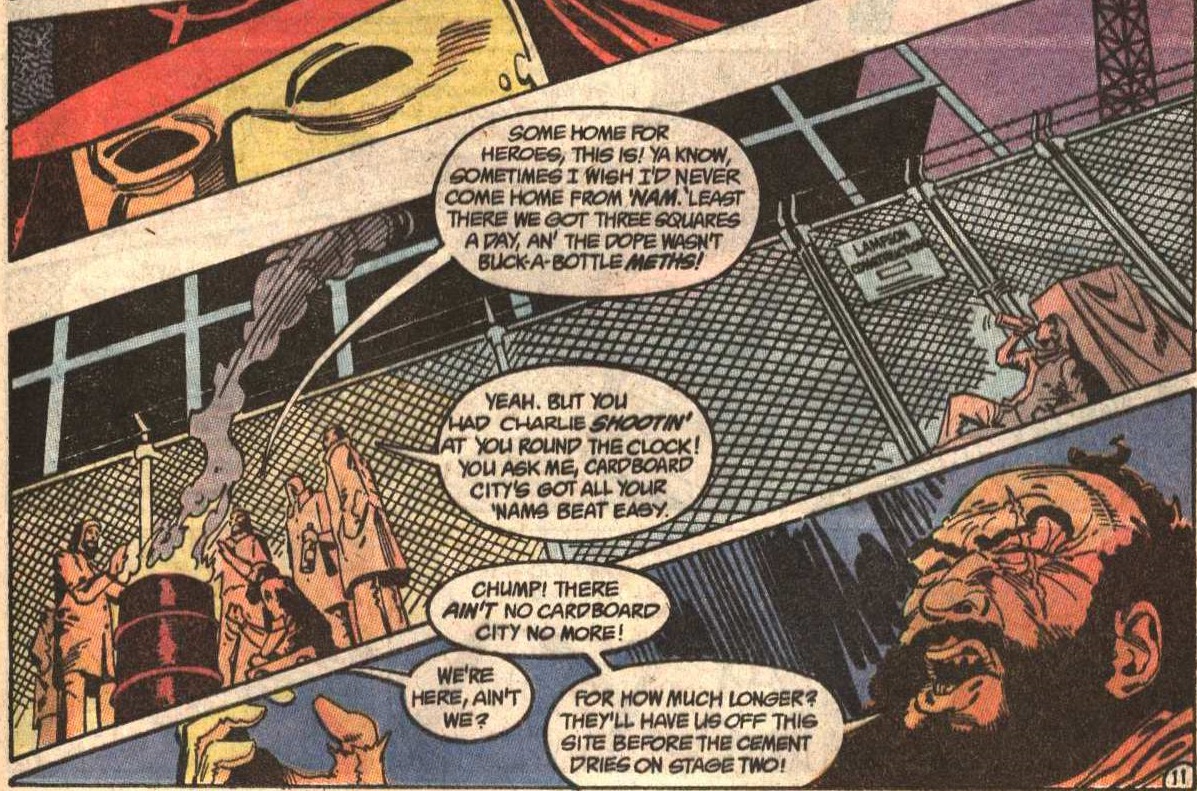

Legs’ first big moment near the spotlight came up the following year, with ‘Anarky in Gotham City’ (Detective Comics #608-609). In this arc, Legs began supporting the vigilante Anarky after a bank bought the piece of land where he lived – also known as ‘Cardboard City’ – and kicked him and his buddies out.

Detective Comics #609

Detective Comics #609

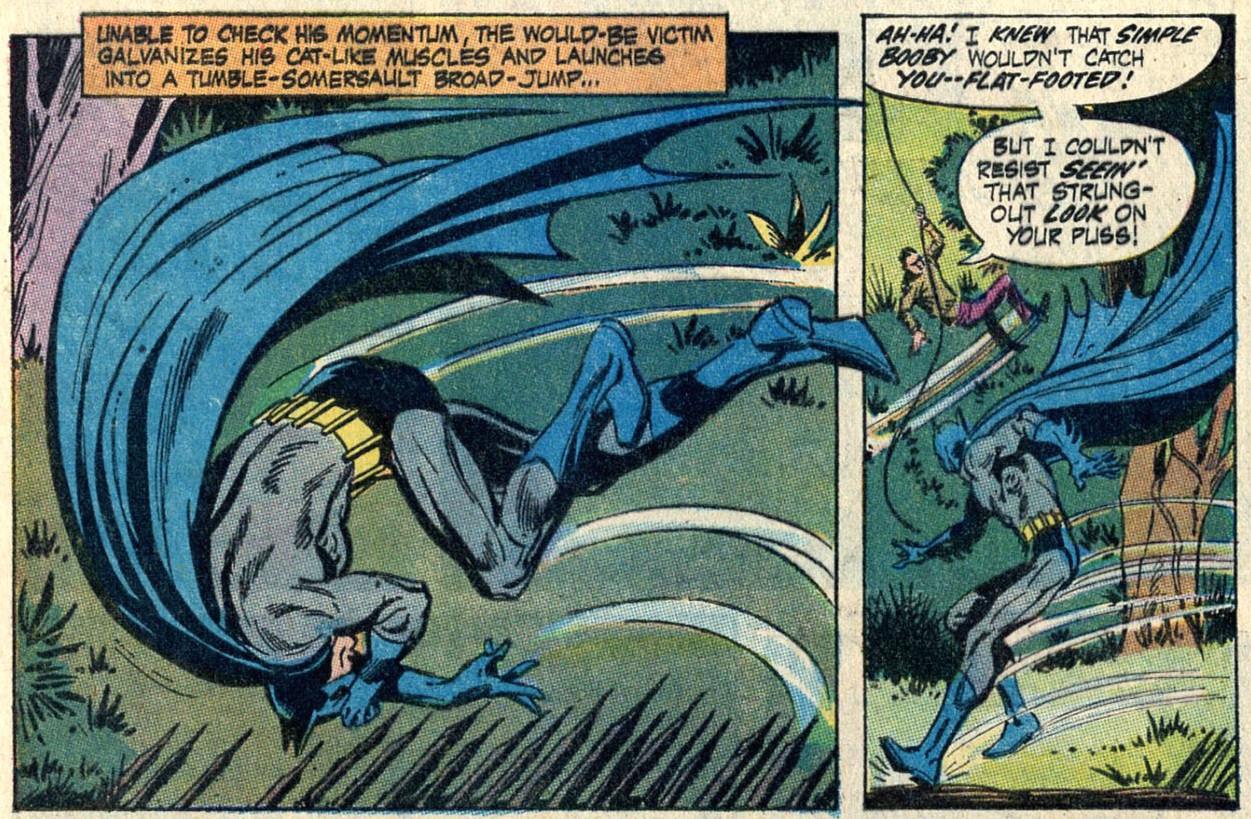

Anarky convinced the homeless crew to attack the construction site. When Batman took the side of the establishment, they attacked him and Legs actually managed to catch the Dark Knight by surprise:

Detective Comics #609

Detective Comics #609

(You’ve got to love Batman’s expression in that final panel. Gods bless you, Norm Breyfogle!)

When Grant and Breyfogle moved from Detective Comics to Batman, they took the homeless crew with them. The crew showed up in ‘Identity Crisis’ (Batman #455), where they had a nice scene with photojournalist Vicki Vale, who was doing a piece about homelessness for the Gotham View magazine (it came out in Batman #460). They were also attacked by the city’s latest serial killer and Legs was one of the few survivors.

The cranky vet continued to work with Anarky. In ‘Tomorrow Belongs To Us’ (Batman Chronicles #1), he helped the iconoclastic vigilante break into the headquarters of a billionaire media owner. Grant and Breyfogle brought Legs back once again for their 1997 Anarky mini-series. Moreover, Batman saved him when he got trapped in the rubble following the earthquake of the depressing Cataclysm crossover (Shadow of the Bat #74).

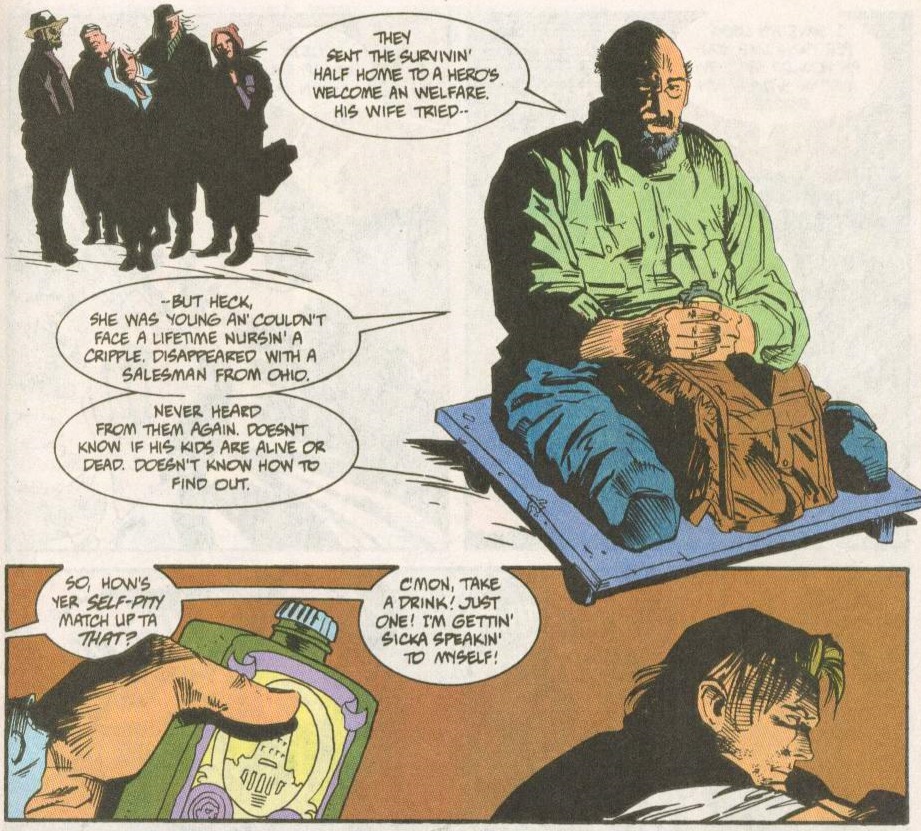

I’ll wrap up with a comic in which we gained a deeper insight into Legs’ experience. In a short tale set in the aftermath of Knightfall, Legs (with a slightly different look, courtesy of Mike Vosburg, Ron McCain, and Dave Hornung) bumped into a homeless Jean-Paul Valley, then recently kicked out of a stint as AzBats. In this memorable sequence, Legs reminded the sad bastard that, as gritty and angsty as comic book heroes got in the early ‘90s, they should at least take some consolation in the fact that they lived outside of the real world: