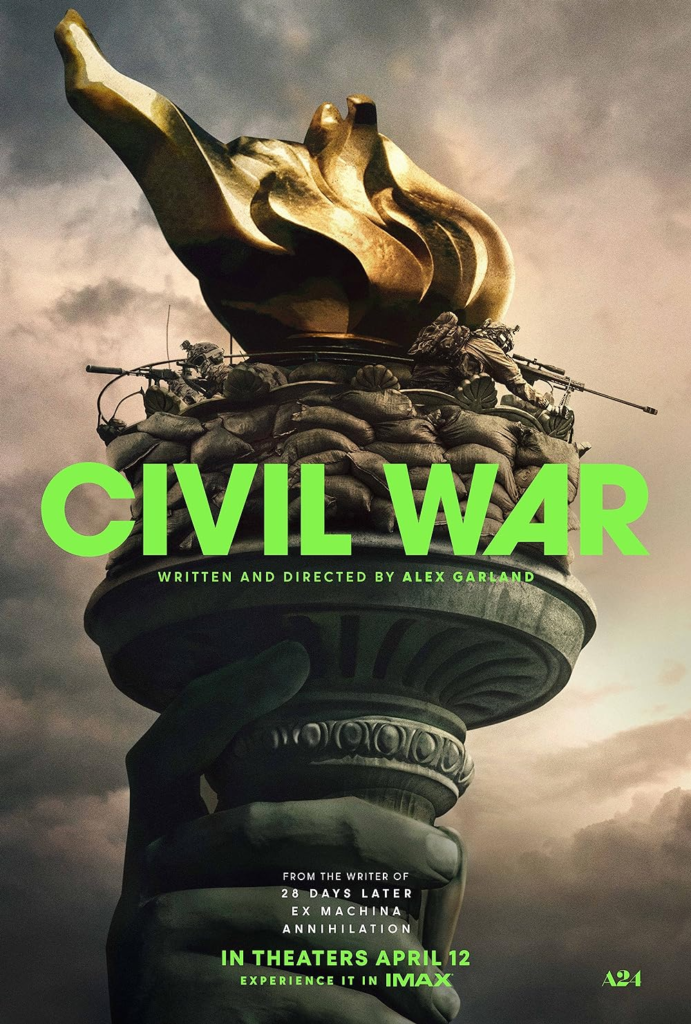

Just some loose thoughts on the Civil War film… No, not the MCU one, I’m talking about the one set in a dystopia where secessionist states are fighting against the US president.

Matt Zoller Seitz has summed up the initial reactions to Civil War: ‘(1) an alternative future history of a divided United States that’s intended as a cautionary tale; (2) a technically proficient but empty-headed misery porn compendium that derives much of its power from images redolent of genocide and/or lynching, but ducks political specifics so as not to offend reactionaries; or (3) a visionary spectacular with ultra-violence that might or might not have something important to say but will definitely look and sound great on an expensive home entertainment system.’

I don’t fully share any of these perspectives. Civil War doesn’t strike me as a cautionary tale as much as the kind the film that, by anticipating some elements of what’s to come, is bound to be remembered and referenced in the same way all those old disaster movies or thrillers about terrorism in New York gained a retroactive resonance after covid-19 or 9/11. As near-future history, though, it’s not particularly believable: if there is a breakdown of the US, it seems more likely to entail deep internal division and conflict between factions within communities (Trump voters live next door, not just in some conveniently separated geographic area) rather than what we see in the film, which is a fairly conventional war between states/military forces.

As is often the case, I find it more interesting to consider how the movie uses past events, as it relocates to the US imagery from wars in Germany, Vietnam, Iraq, etc, so that what seemed remote now seems close and blended. By simultaneously evoking estrangement and recognition, Civil War may perhaps suggest to Americans the feeling of witnessing from the inside those societies’ collapse… or of witnessing such collapse through the outside lens of foreign correspondents. It’s not so much a challenging statement as yet another reminder of how differently Western empathy works towards privileged places in comparison to sites like Gaza.

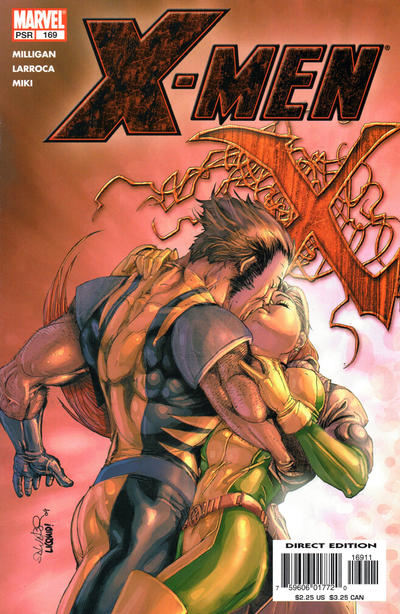

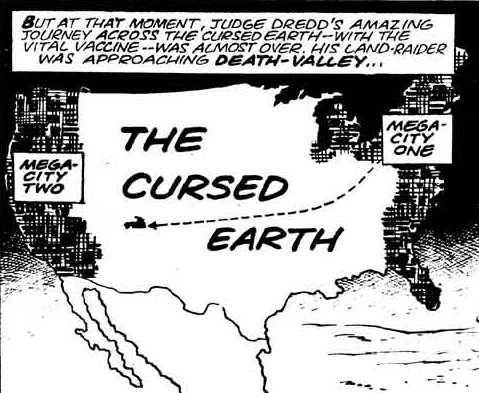

2000 AD #81

On the picture’s ostensible apolitical stance, i.e. the way it avoids taking sides while emptying the conflict of discernible ideologies and reducing the backstory to vague allusions, well, this is actually something I liked: I went in fearing a preachy polemic, so I found Civil War’s minimalist world-building, close-to-the-ground storytelling, and relatively spare dialogue to be refreshing and stimulating.

The main reason for this choice may have been cynical commercial interest and political cowardice, trying not to alienate too many possible target audiences, but the result is nevertheless thought-provoking. The fact that the ambiguous scenario can be read both ways, as either a revolt against a Trump figure or as a right-wing coalition elevating January 6th to the next level (the sequence with Jesse Plemons is the only one that conveys clear ideological stakes, but it remains uncertain which side he’s fighting for or if he has just gone rogue) signals the political confusion and the very unpredictability of our current moment.

Likewise, by exploiting and sensationalizing graphic violence, including that of real-world tragedies, the film reflects the attitude of the central characters, a group of desensitized reporters more concerned with thrills and aesthetics than with the political implications or the actual suffering they depict. If Civil War is about anything, it’s about the cold distance of sensationalist war-related journalism, which is not to say that it has anything new or deep to say… Indeed, more than the superficial politics, I was struck by the superficial take on photojournalism, with everybody treating photos as if they don’t have angles or meanings or points of view – they’re just ‘great’ when they look impressive and shocking.

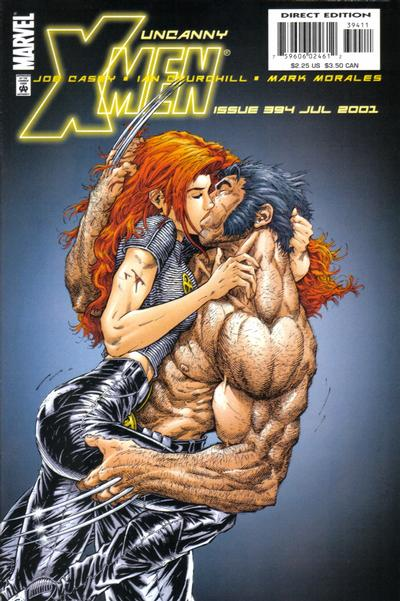

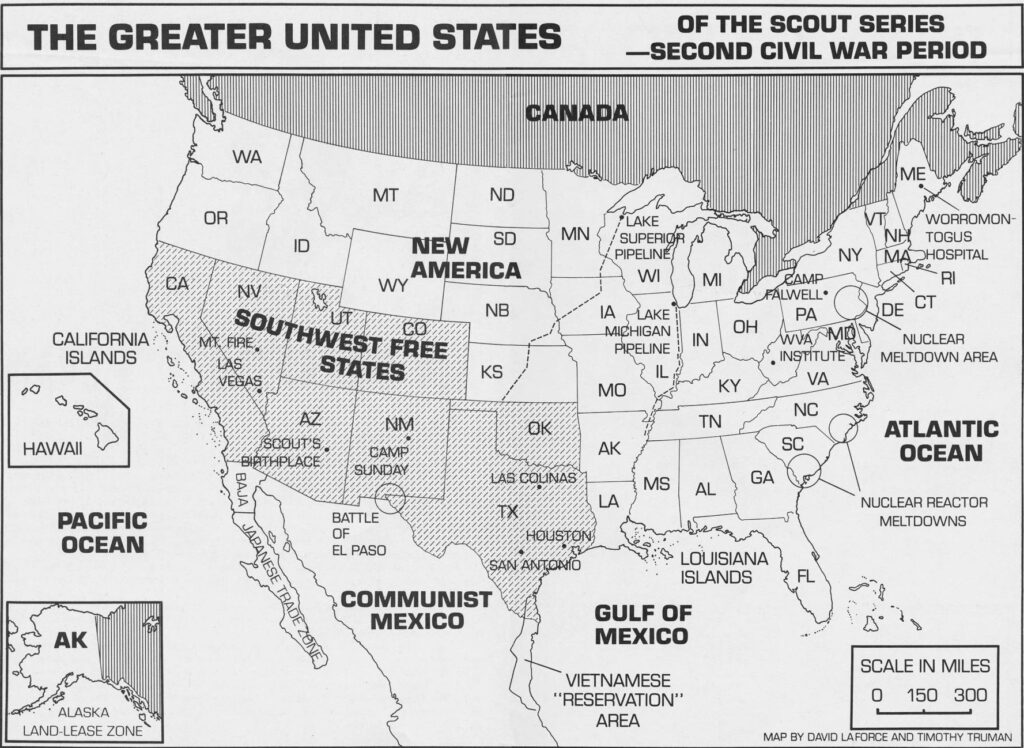

Scout Handbook

This brings us to (3), that is to say, to the notion that Civil War is best appreciated as a visceral rather than cerebral experience, providing a string of perversely entertaining set pieces, enhanced by the provocative context but not necessarily at its service. Unlike what the poster and trailer might suggest, this is not a dumb blockbuster drawing on obvious American icons to stage a relentless orgy of spectacular action and large-scale destruction but rather something closer in style to Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men. Still, it’s a tense, immersive road movie where every stop involves a new mystery and obstacle, so the most satisfying way to enjoy it is perhaps on a moment-by-moment basis, hanging out with these characters instead of theorizing about the bigger picture.

This matches my general approach to Alex Garland, whom I think consistently uses ambitious high concepts to fuel moody yet functional genre pieces, frustrating those in search of insightful science fiction while rewarding those (like me) for whom the smart elements are a bonus adorning stylish sci-fi adventures. So, underneath the Tarkovsky veneer, just as 28 Days Later was a post-apocalyptic zombie flick, Sunshine a slasher in outer space, Dredd a cyberpunk action fest, Ex Machina a chamber piece psychological thriller, Annihilation a – flawed yet compelling – slow-burn monster-hunting shooter, Devs a spy-fi yarn, and Men a psychedelic body horror riff (which eventually loses its way precisely by pushing the allegorical dimension), Civil War boils down to a solid war movie with an edgy twist.

The thing is that, even with adjusted expectations, Garland’s film is neither particularly original in terms visuals nor especially involving in terms of characterization (despite the nice performances, in particular Kirsten Dunst, who comes across as truly broken and tired). The notion of the US as a modern battlefield was memorably mined in the preposterously silly Red Dawn, forty years ago, and you can find much more complex, fleshed out war correspondents in Under Fire, to cite two of Gotham Calling’s top Cold War films.

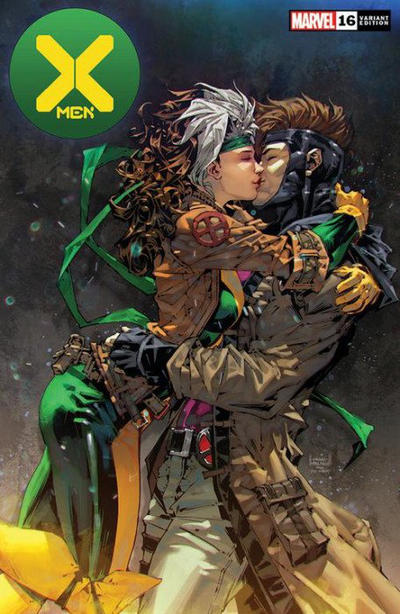

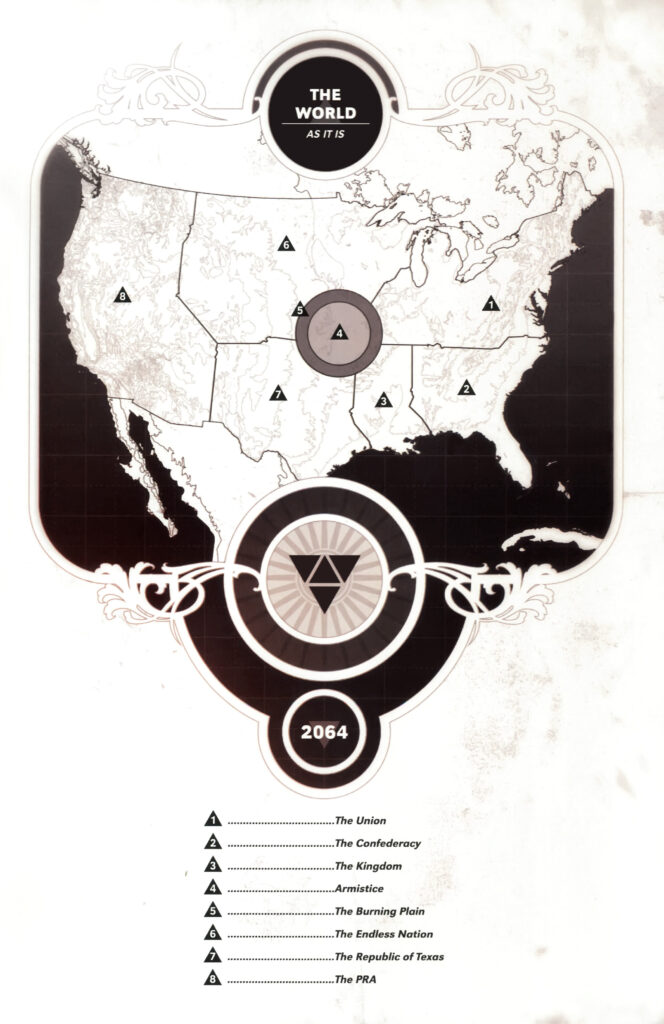

East of West #1

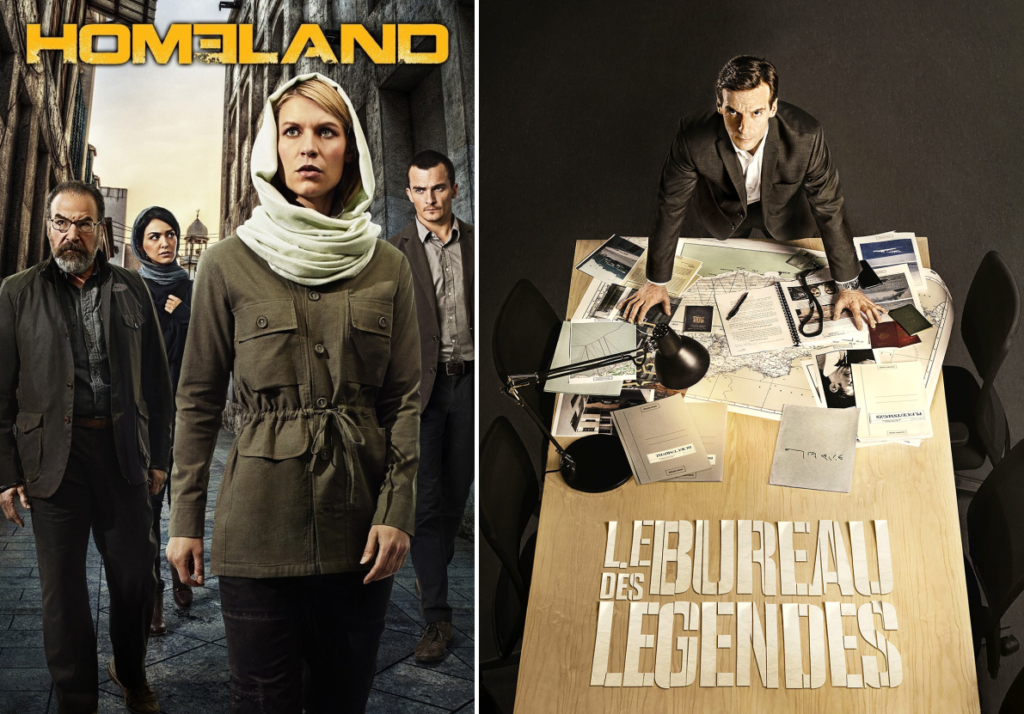

I get why some viewers – especially critics – would demand more. A24 productions have such a serious, pretentious tone that they keep hinting towards something sophisticated and meaningful, yet not always living up to that promise. Recently, the company was behind Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s controversial historical drama about the domestic family life of Auschwitz’s commandant (whose house was right next to the concentration camp), which actually has a few points of contact with Civil War: both thematize people’s ability to accept and coexist with carnage; both eschew exposition-laden conversations, relying heavily on – and ultimately exploring – our own previous understanding of the world (even if Zone of Interest keeps the Holocaust’s physical violence offscreen, poignantly dramatizing the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ inclination, while Civil War shamelessly recreates that violence, illustrating how even images of death and pain come to be accepted).

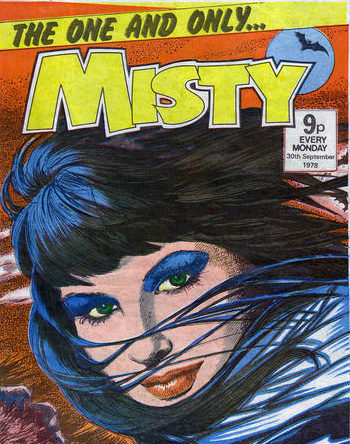

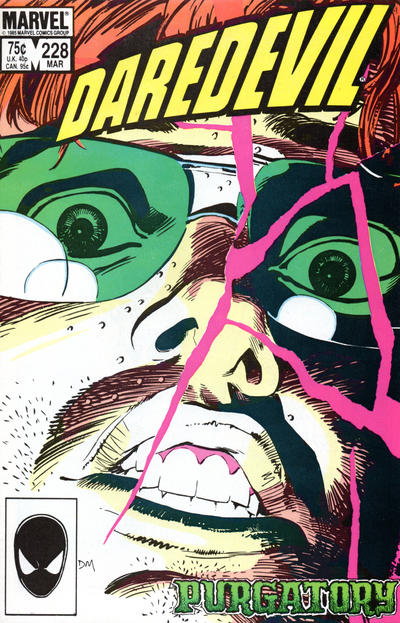

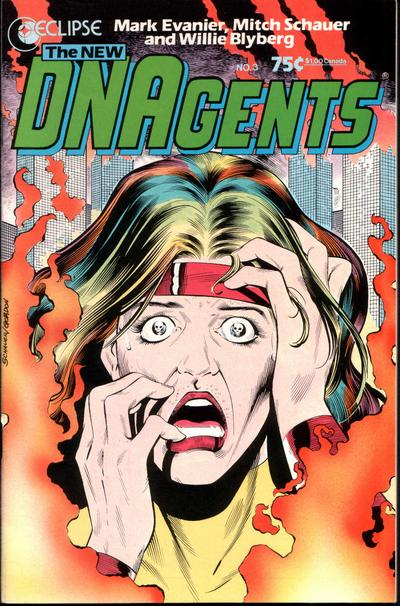

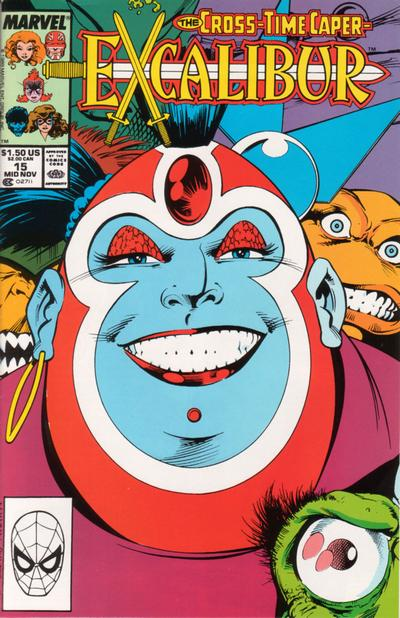

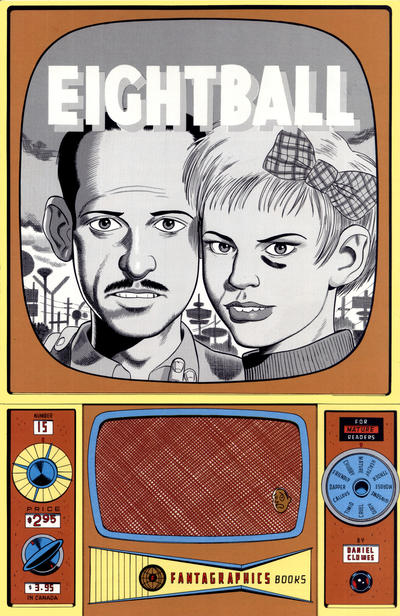

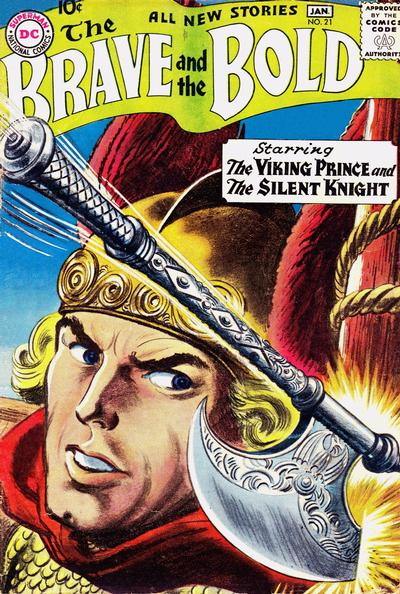

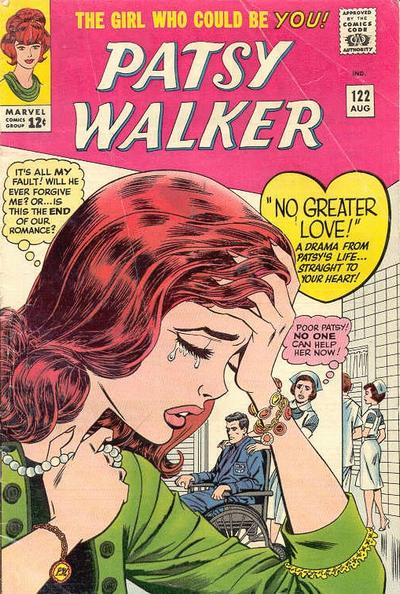

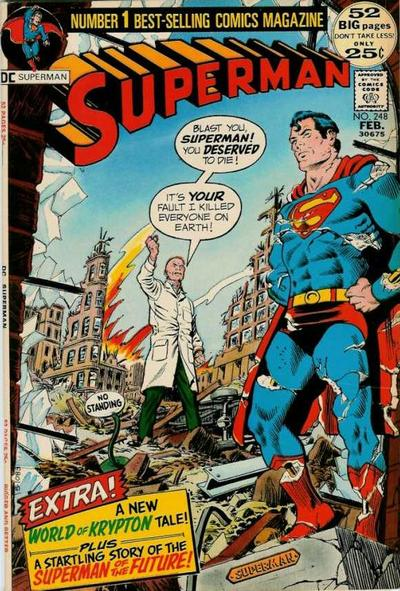

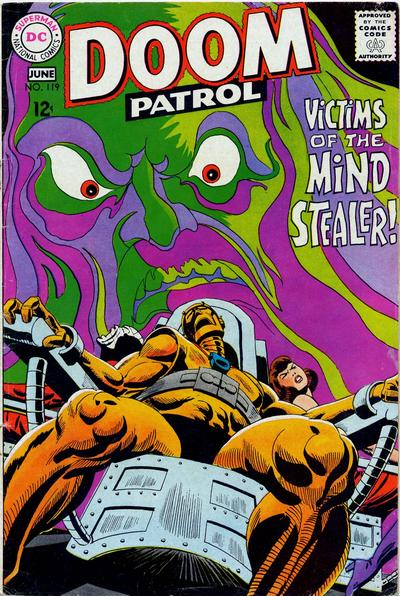

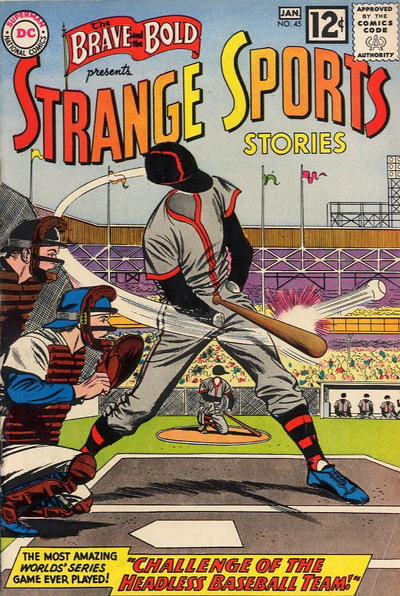

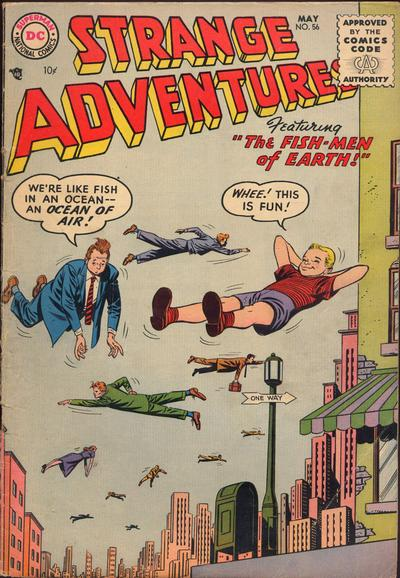

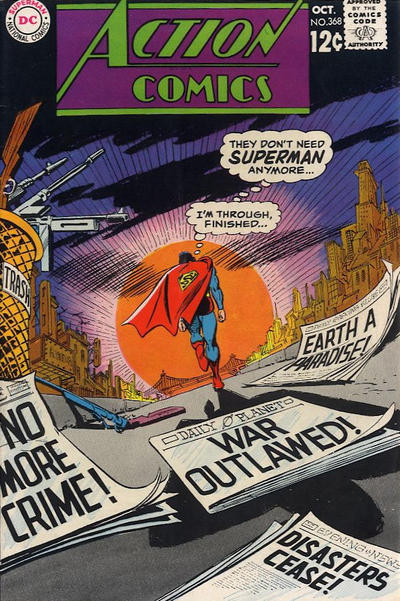

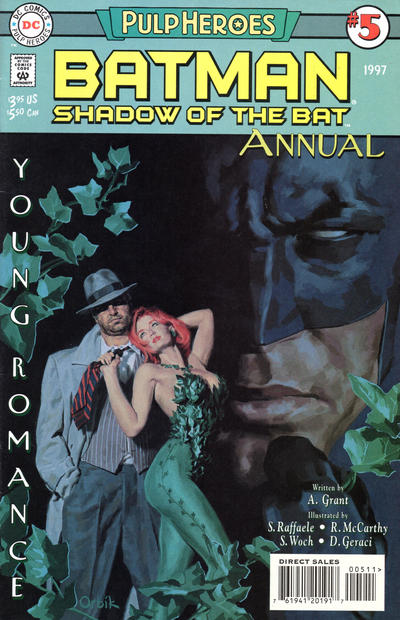

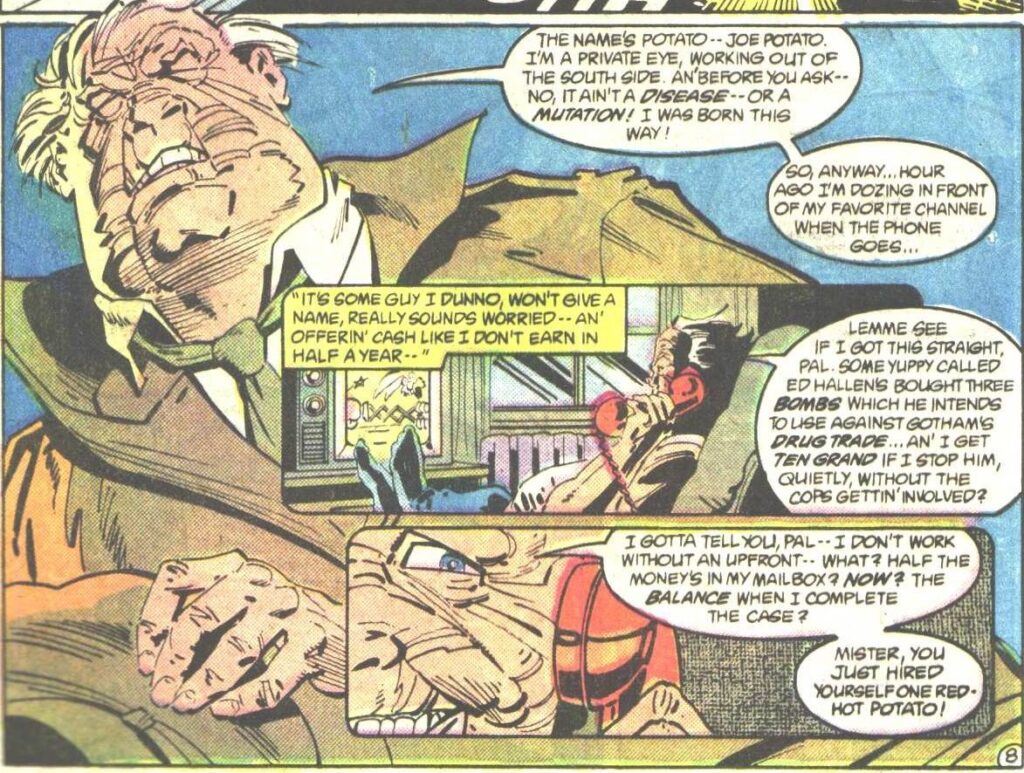

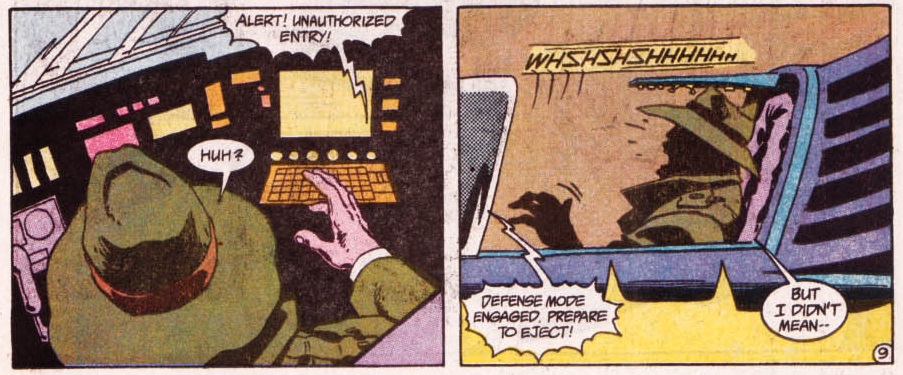

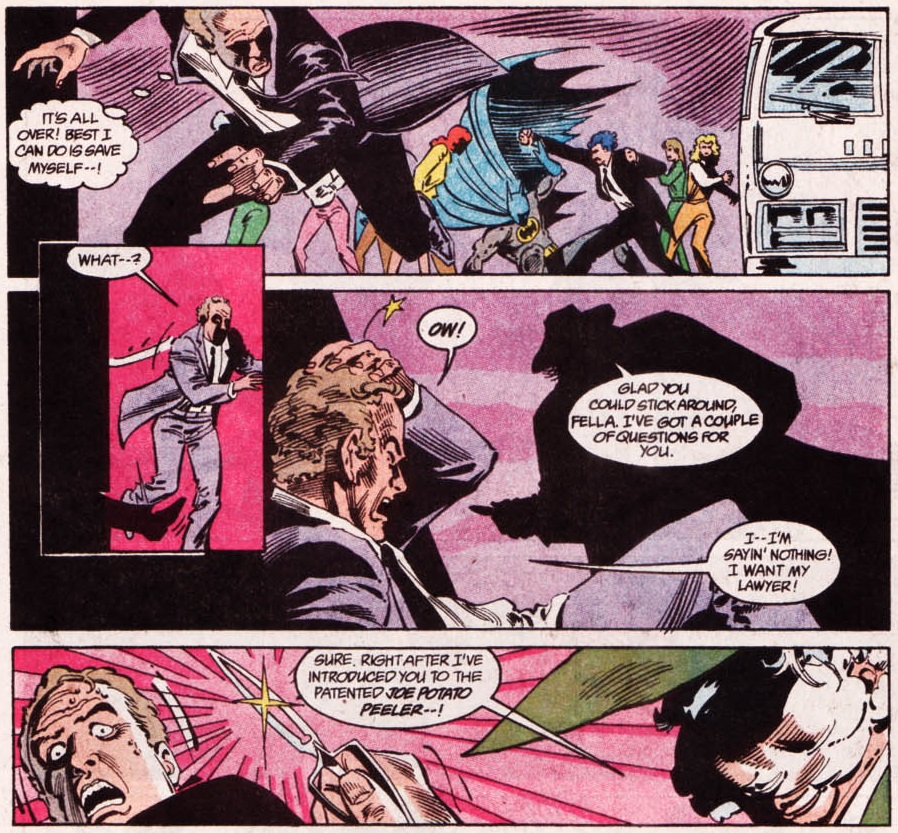

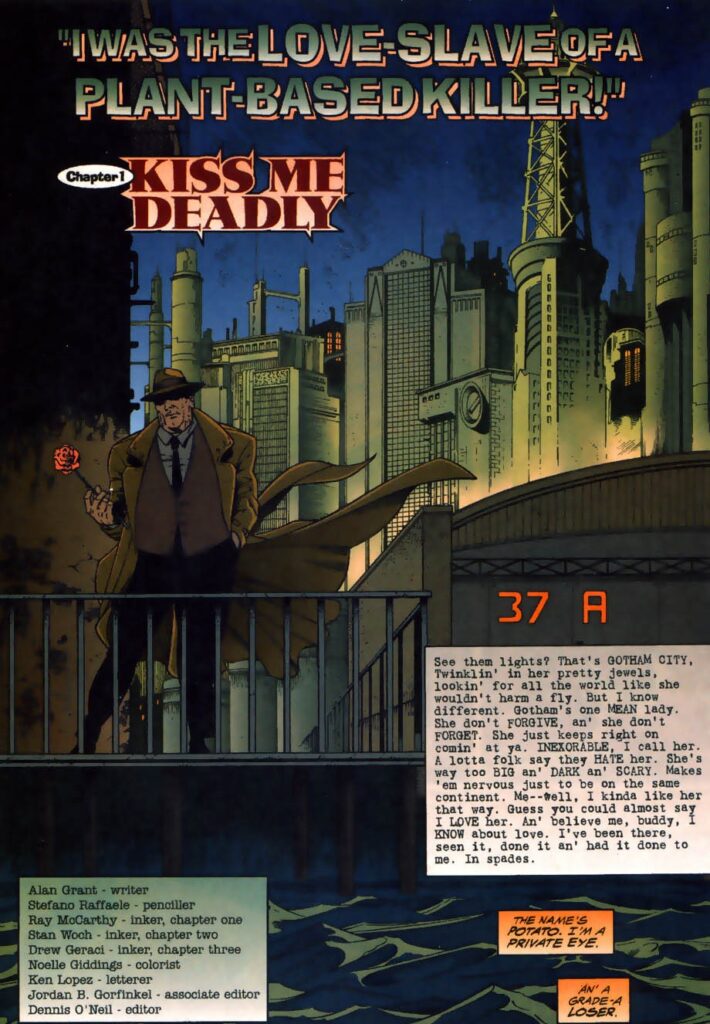

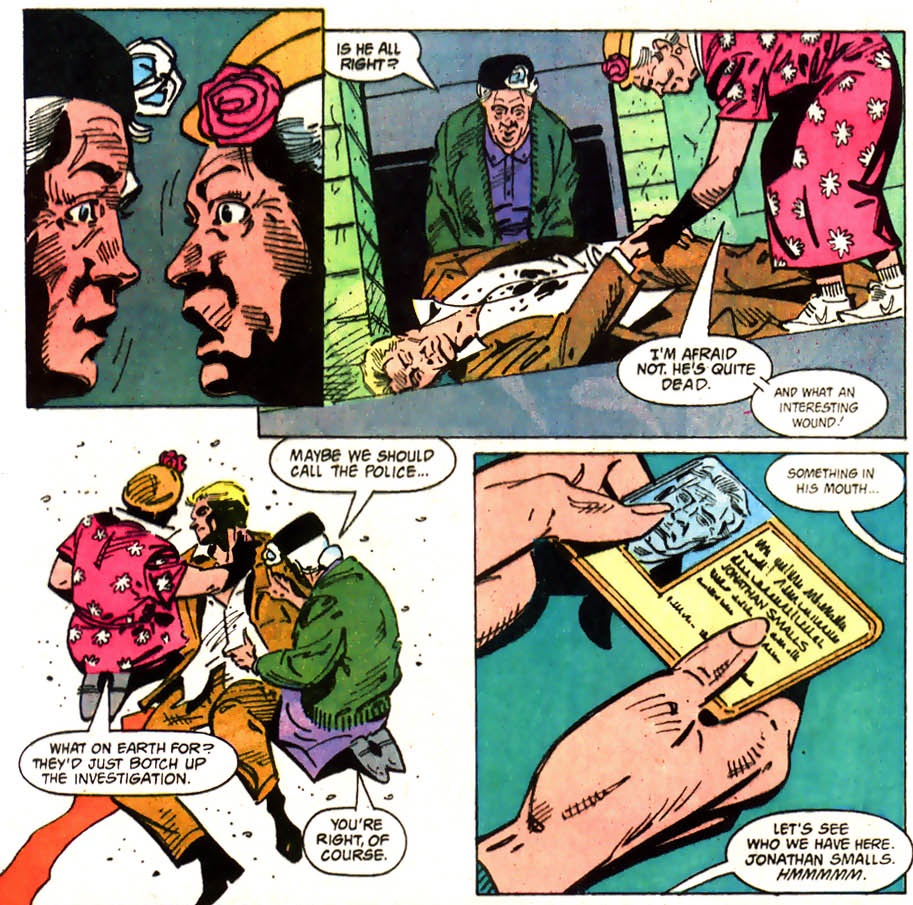

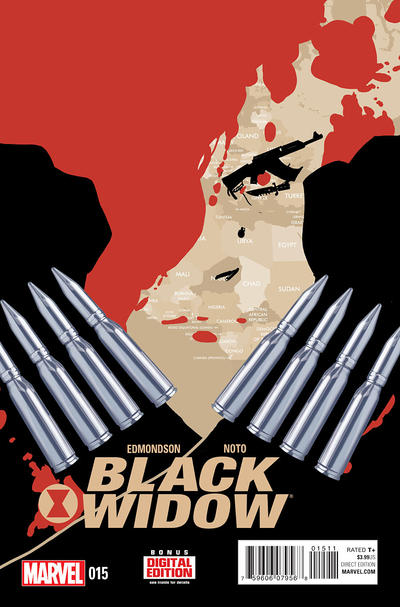

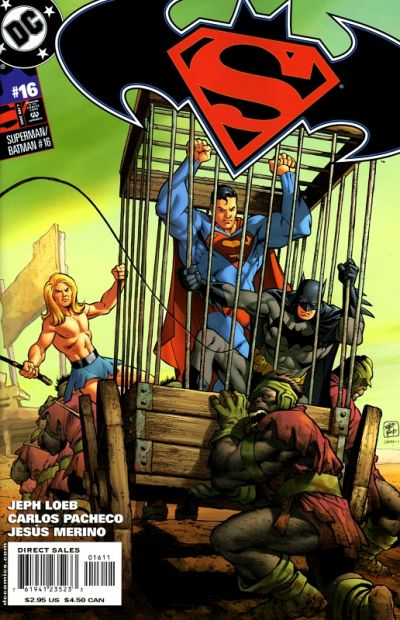

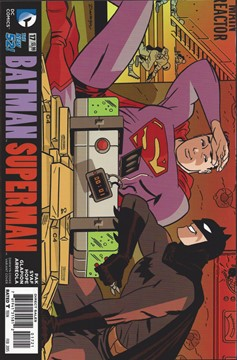

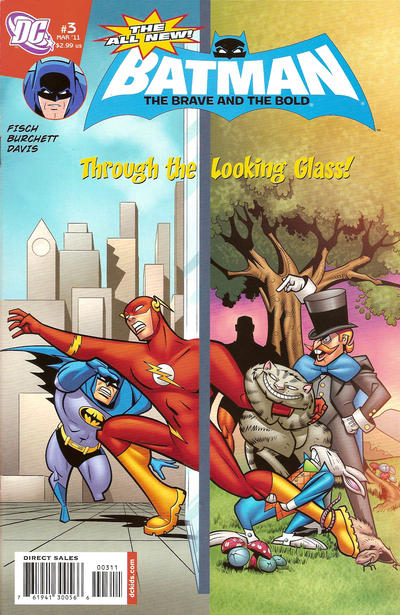

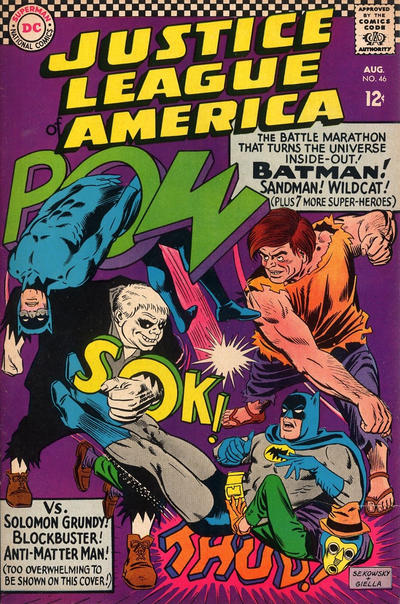

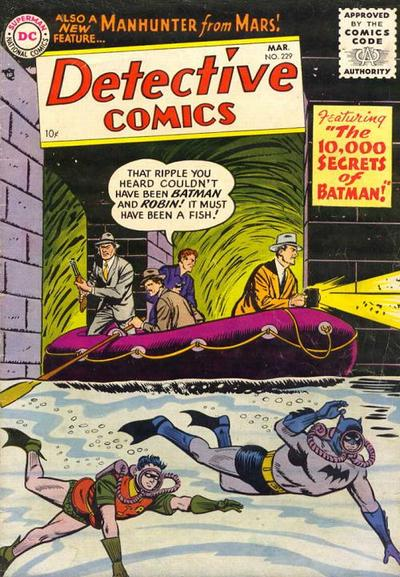

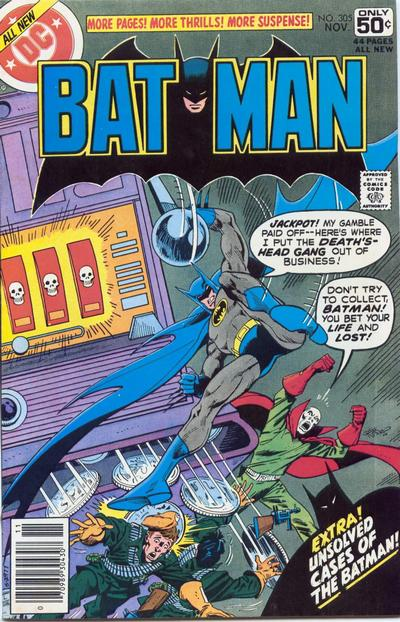

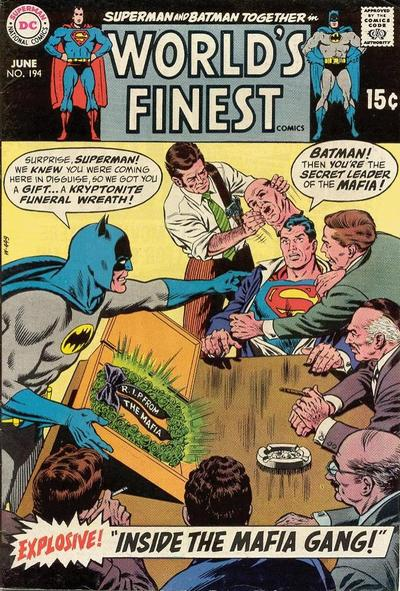

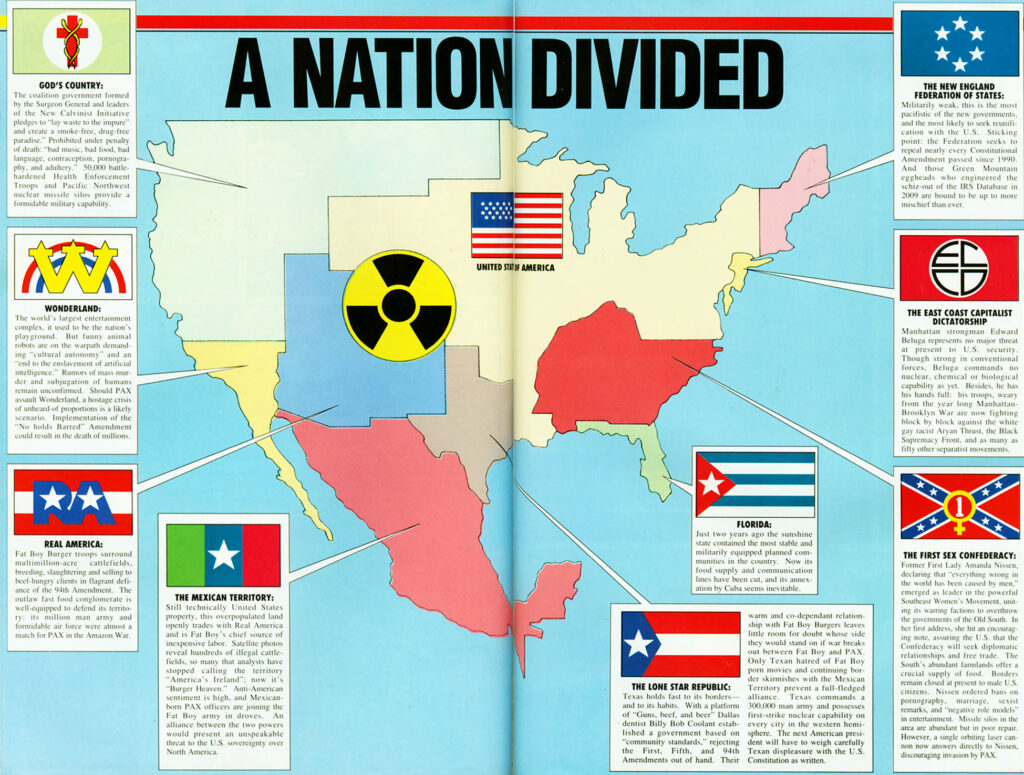

By now, we’ve all seen countless versions of the destruction of the United States, many of them much more imaginative than what you find here. For instance, the maps I’ve used in this post come from comics that did it in a more maximalist – and surrealist – fashion. I find them all very cool and fun, but I suppose what sets Civil War apart, at the end of the day, is precisely its low-key vibe, as if underlining how mundane and increasingly familiar this prospect has come to feel.

I’m certainly not the first to point out that apocalyptic fiction has become less and less futuristic. Then again, as Ursula K. Le Guin put it as far back as 1969, in the introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness, classic sci-fi has always tended to be more descriptive than predictive: ‘The weather bureau will tell you what next Tuesday will be like, and the Rand Corporation will tell you what the twenty-first century will be like. I don’t recommend that you turn to the writers of fiction for such information. It’s none of their business. All they’re trying to do is tell you what they’re like, and what you’re like – what’s going on – what the weather is now, today, this moment, the rain, the sunlight, look!’

Give Me Liberty #4