Drugs have traditionally played a substantial role in Batman comics (hell, in the whole medium). The Dark Knight has put away his share of drug dealers – from run-of-the-mill villains (your prototypical crime fiction trope) to the kind of outlandish characters that populate Gotham’s bizarre underworld. His stories have also featured a number of memorable junkies, such as Joey Redwine (in ‘The Spider’s Ninth Leg!’) or Studs (the protagonist of ‘Terminus’).

Moreover, the creators of Batman comics sometimes appear to be under psychotropic influence themselves…

Or, if not directly under the influence, at least trying to simulate its effects…

As encompassing as the drug motif is, however, some comics have tackled it more head-on than others. With that in mind, I want to look at a few stories that have sought to explicitly engage with the topic of substance abuse and say something a bit more ambitious about it.

One of the most mature efforts was ‘Flying Hi’ (Detective Comics #561, cover-dated April 1986), written by Doug Moench, with art by Gene Colan, Bob Smith, and Ricardo Villagran. Despite a florid opening narration, this is a restrained, low-key tale. Jason Todd (the second Robin) has a crush on a new girl at school, Rena, who invites him to get high with her. He discusses the issue, first with Batman and then with the girl, who is mostly looking to fit in. After half the comic with people talking, we get some small-scale action scenes as the class stoners try to rob a pharmacy. The ending – like the beginning – suggests that romantic joy is the best kind of high (which sounds cheesy, but it’s actually handled in an endearing way).

Moench’s script – combined with the relatively naturalistic style of Colan’s pencils and Adrienne Roy’s colors – manages to avoid caricature, as everyone in ‘Flying Hi’ seems to have a more or less realistic grip on what they’re talking about. His work even found praise in the not-exactly-superhero-friendly The Comics Journal (albeit by being treated as an exception to the rule). In the article ‘Flying High and Flying Low’ (issue #108), Steve Monaco argued that, in contrast to ‘Marvel’s typical wacko-junkie and pusher-killer approach,’ this Batman story ‘offers a soft-spoken, intelligent tone to its anti-drug message that is a much welcome change of direction, and it has a pertinence to the world of its intended audience that all the other supposedly relevant comics (and comics writers) should emulate.’

Detective Comics #561

Detective Comics #561

Steve Monaco points out that because this dialectic method is not used combatively (for example, with an aggressive line like ‘Why would someone as smart as you want to do something as totally stupid as taking drugs?’), the ensuing dialogue ‘has a ring of truth, even if it is a bit whitewashed and cutesy for some adult tastes.’

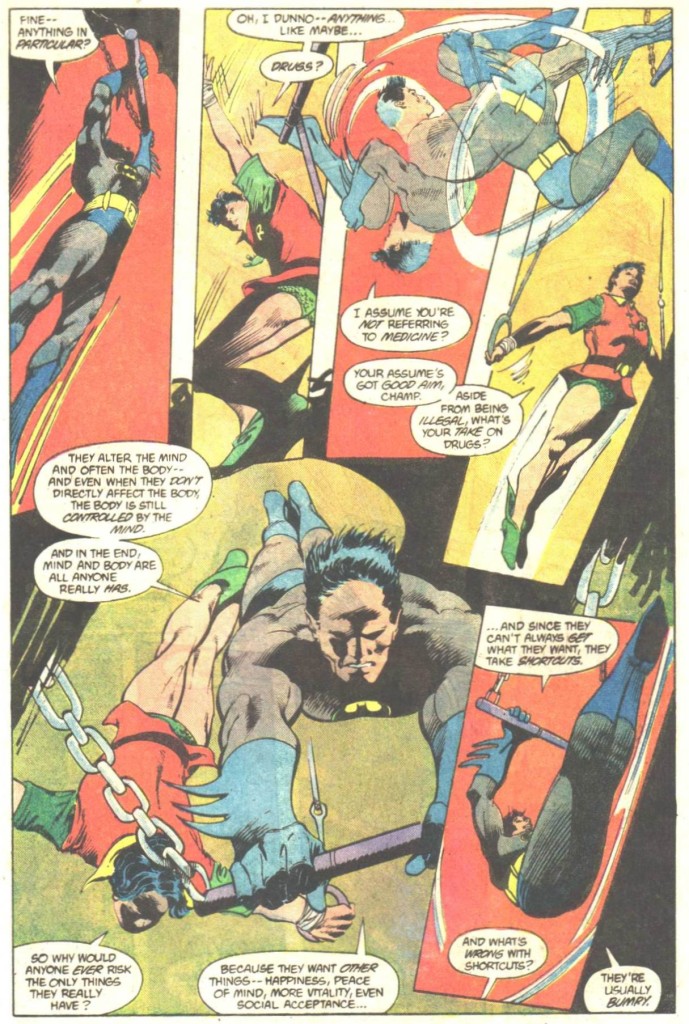

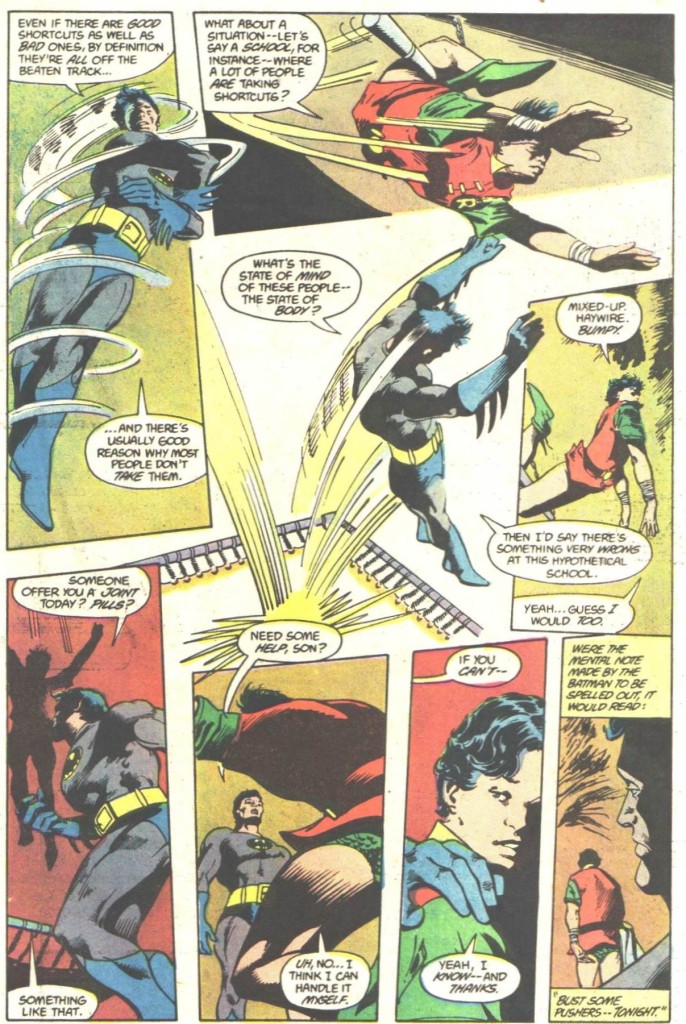

For me, the pivotal scene occurs early on, in the Batcave, when the Caped Crusader proves to be an understanding father figure, talking to Robin openly and with some nuance about the issue:

Detective Comics #561

Detective Comics #561

(The fact that they are literally flying high during the conversation is your obligatory visual pun, typical of Moench’s 1980s’ run.)

On top of everything else, this is a refreshing take on Batman, far from the righteous extremism of other depictions. Bruce doesn’t act especially controlling or judgmental in front of Jason (even though, true to character, he does go out and bust a horrible pusher later on… a scene that is probably meant to contrast the satisfying simplicity of Bats’ pulp fiction world with the shadier reality of Jason’s school life). I really like their matter-of-fact exchange both as a solid moment of bonding between the Dynamic Duo and as a lighthearted alternative to the usual heavy-handed approach to the subject matter.

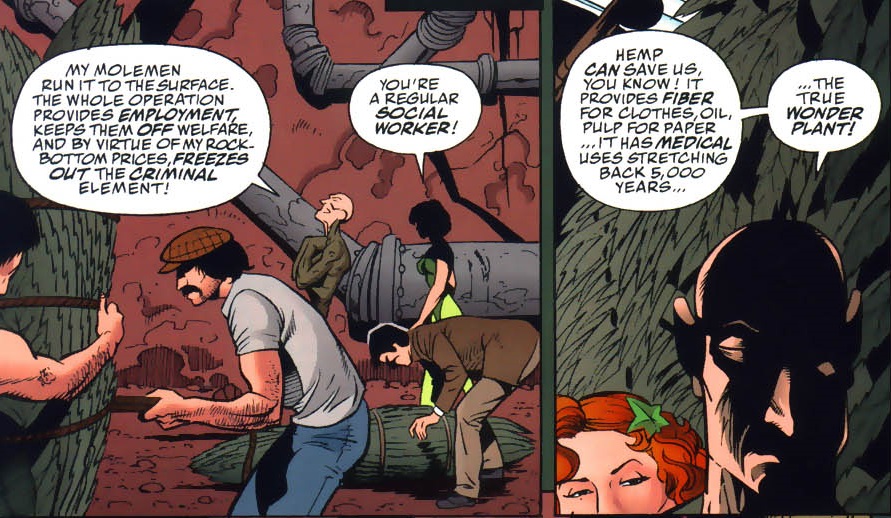

But what about those other works – the ones with a more sensationalist, exploitative take on the malefices of dope consumption? You’d think the most likely place to find them would be in the oeuvre of Alan Grant, the king of over-the-top Batman drug comics, especially in ‘Leaves of Grass’ (Shadow of the Bat #96-98, cover-dated November 1996-January 1997), which revolves directly around pot.

In part, you’d be right. This three-parter concerns a drug war prompted by the fact that a new supplier is providing Gotham dealers with genetically-enhanced weed at half the cost of their regular score, which leads established suppliers to turn to brutal force to try to keep their dealers in line. The twist is that the new supplier in town is actually the camp DC villain Floronic Man, whose latest body is made out of marijuana and who sounds stoned out of his mind… In a particularly ridiculous development, Floro has his two voluptuous henchwomen kidnap Poison Ivy because he wants to make a hemp baby with her!

Shadow of the Bat #57

Shadow of the Bat #57

As you can tell from this excerpt, ‘Leaves of Grass’ is full of the kind of expository passages with ham-fisted factoids and statistics often associated with PSAs. Plus, there is a whole subplot about a classmate of Tim Drake (the third Robin) smoking a joint for the first time and having a bad trip, which comes across like a preachy cautionary tale.

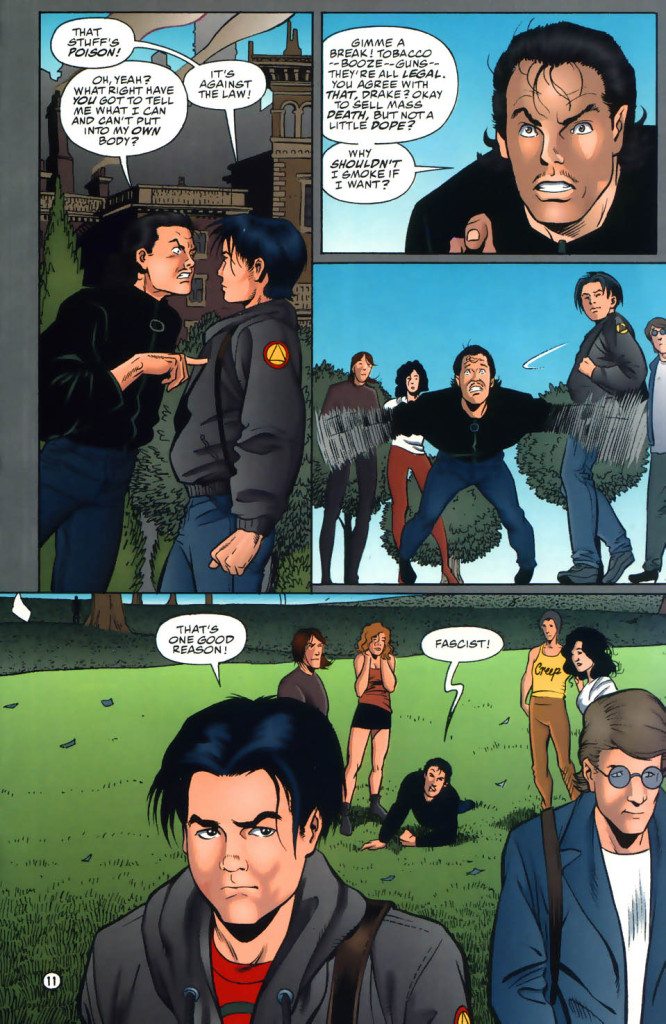

That said, the comic is not as egregious as it may sound. The art by Dave Taylor (pencils), Stan Woch (inks), and Pamela Rambo (colors) downplays Grant’s propensity towards excess, keeping the story grounded. And for all the constant sermonizing, the dialogue ultimately stays true to each character (as long as you remember that Floro and Poison Ivy are meant to be deranged). The sequences in Tim’s schoolyard, for example, are not that contrived if you bear in mind that they are meant to capture the interplay between doofus teenagers:

Shadow of the Bat #56

Shadow of the Bat #56

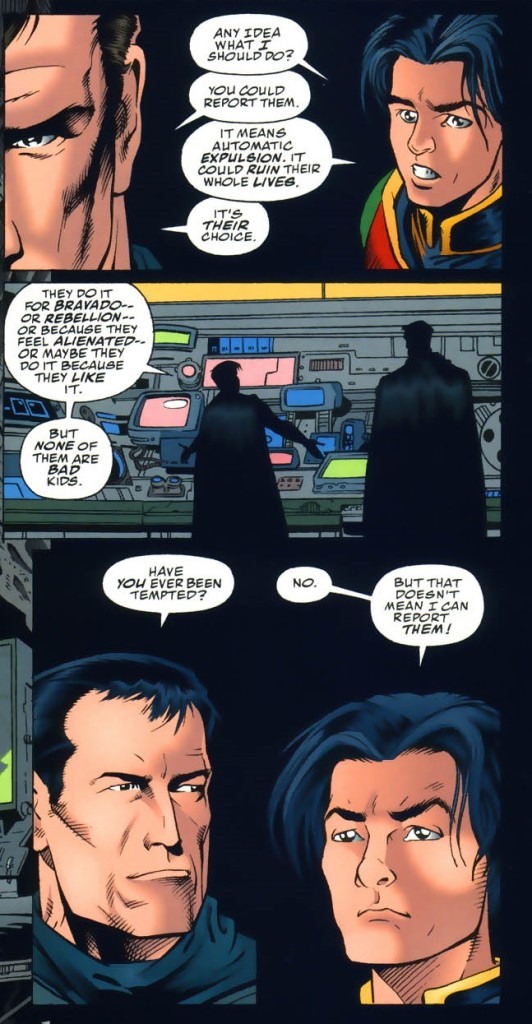

Likewise, the equivalent of Jason’s exchange with Batman in the Batcave, although handled differently, doesn’t veer too far off the chart. Yes, the scene is more stilted and Bruce sounds less tolerant than he did in ‘Flying Hi,’ but that matches the overall characterization in the story – and in mid-90s’ Batman comics – where the Dark Knight is the inflexible one and the Teen Wonder a more humanistic voice of reason.

Shadow of the Bat #56

Shadow of the Bat #56

Moreover, there is a nice ambiguity about the whole thing. Alan Grant, clearly aware of the reputation of drug-related fiction and anti-drug propaganda, gave each chapter a tongue-in-cheek title: the first one is named after a trippy TV show (‘Twin Peaks’), the second one after an infamous anti-marijuana film (‘Reefer Madness’), and the last one uses drug terminology to reflect what takes place in the issue at various levels (‘Comedown’).

He also tries to illustrate a fuller debate. It’s not just Floro who presents pro-pot arguments – in the final issue, the action is juxtaposed with a school presentation by Tim Drake about the dodgy history of hemp criminalization and the contextual – and racist – background of its ban, in addition to the harsh social consequences of marijuana’s illegal status (‘in 1990, almost 400,000 Americans were arrested for its possession or use’).

The indictment of the War on Drugs is voiced by Commissioner Gordon (‘the more we wage our war on it, the more people want to use it’), whose frustrated outlook makes for an effective counterpoint to Batman’s no-compromise brand of conservatism. Anticipating the strategy of the – much more sophisticated – third season of The Wire, ‘Leaves of Grass’ illustrates the potential of decriminalization with some counterfactual statistics:

Shadow of the Bat #58

Shadow of the Bat #58

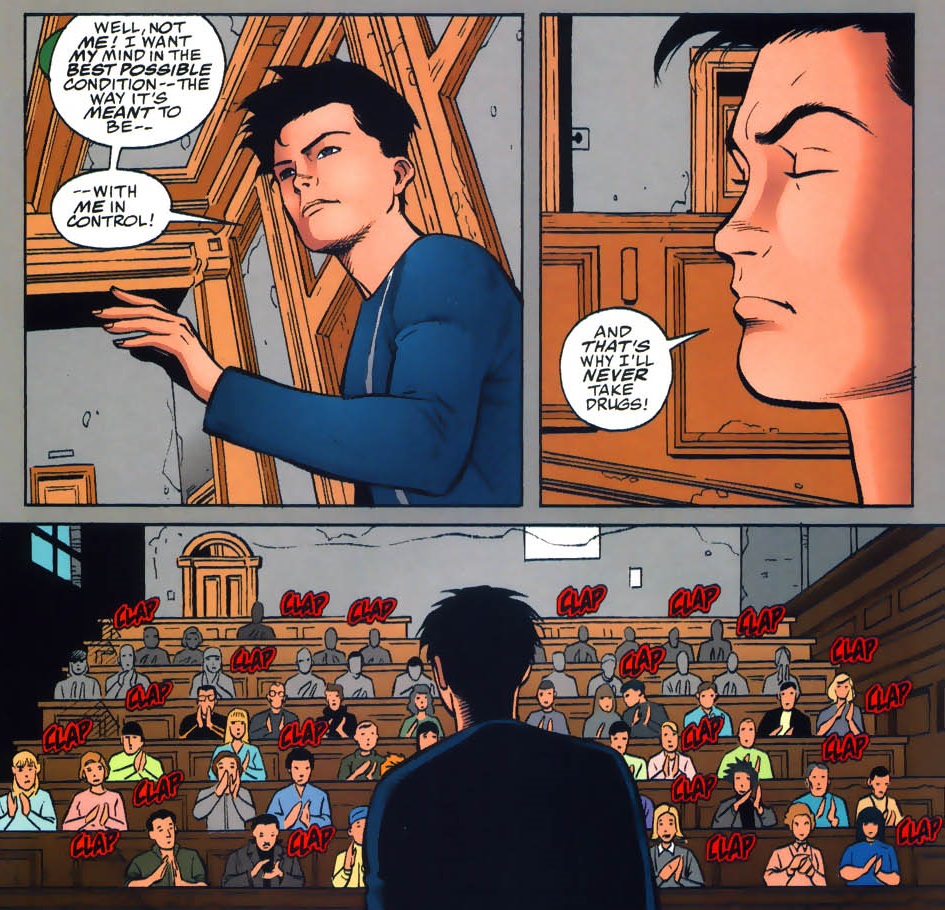

Against this background, the point of Tim Drake’s closing monologue to his class goes further than a statement against taking drugs. He – and the comic – stresses the notion that the drug problem isn’t something that can be resolved with threat or violence. It should be handled with frankness and by example. This acknowledgement of the importance of inspiration as a deterrent (rather than force or fear) ties into Tim’s own conflicting notions of heroism, which means that the payoff also works in terms of pushing Robin’s characterization.

Shadow of the Bat #58

Shadow of the Bat #58

Granted: the clapping at the end is probably taking it too far…