As much as Frank Miller milked Superman’s symbolic potential, I also appreciate how much his comics simultaneously ‘humanized’ the character as well. Miller’s interpretation of the Man of Steel may be eccentric, but his Superman is an actual individual and not just a mouthpiece for themes and ideas.

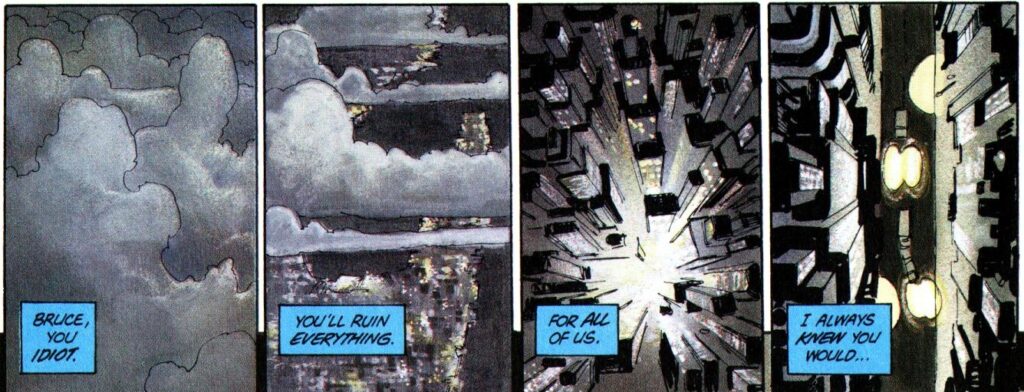

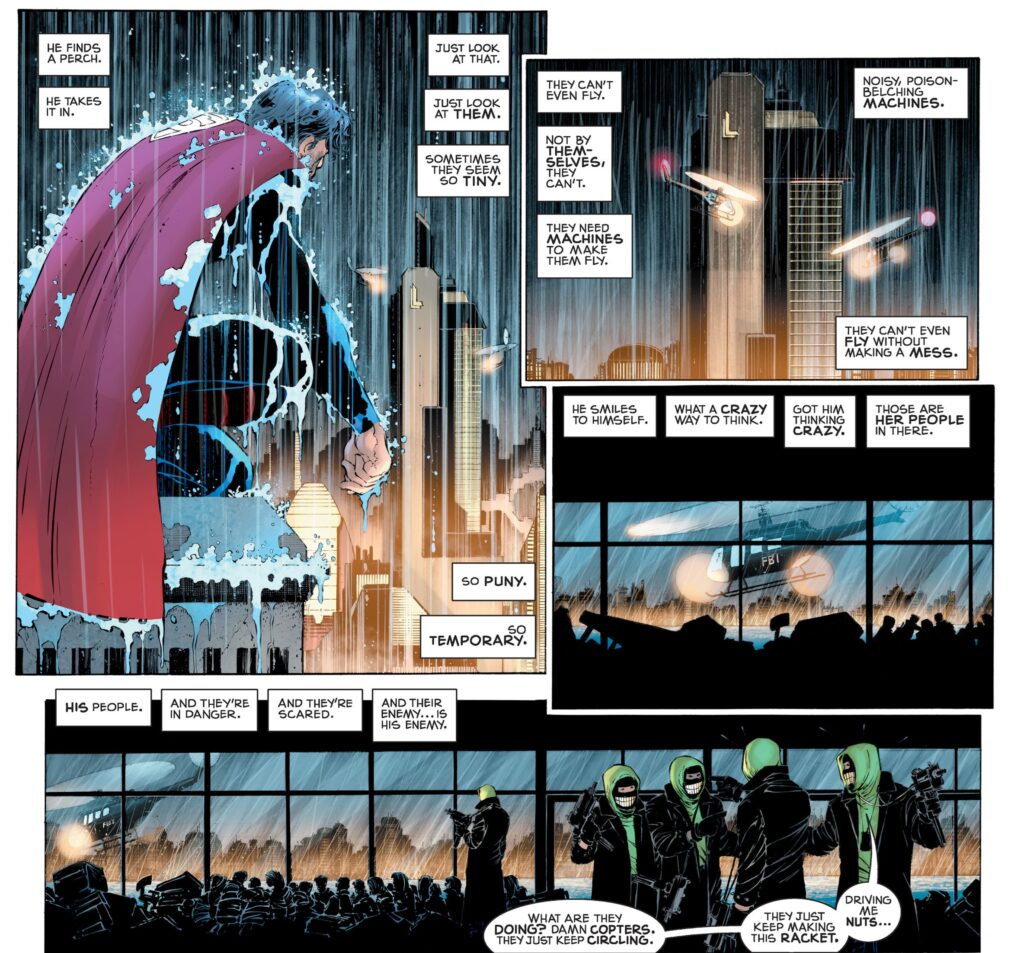

For all of his fascination with over-the-top figures, at his best Miller tends to display a talent for giving his cast gripping individual voices and a believable interiority. If we go back to The Dark Knight Returns, Superman is never *just* a distant symbol. In fact, in one of his first scenes we get to briefly see the world through his perspective, sharing both his sight and his frustrated inner thoughts…

The Dark Knight #3

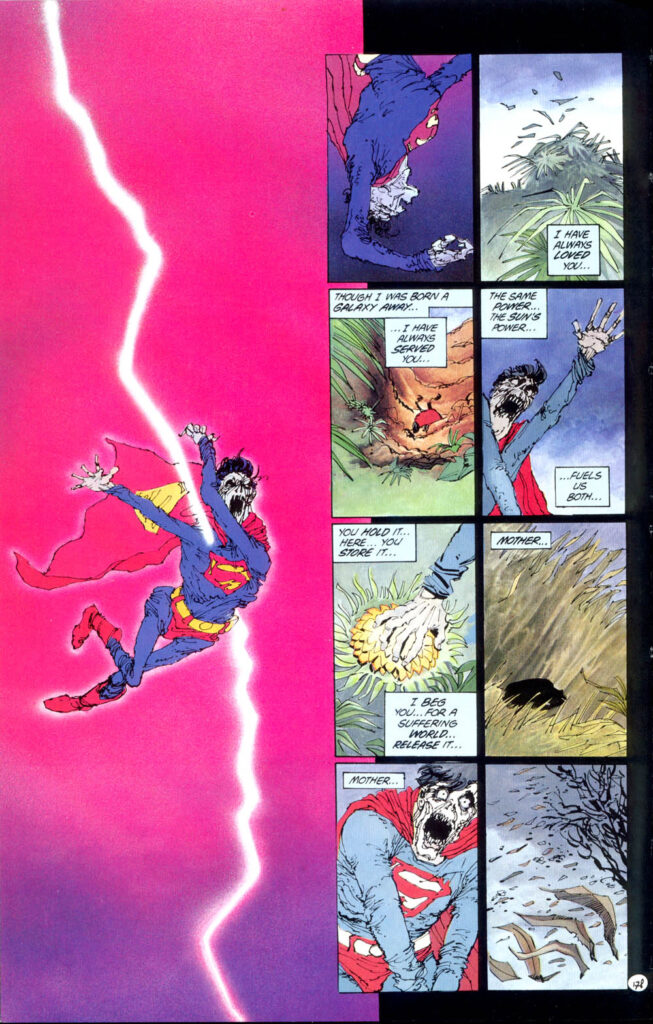

The book is full of touches like this one. When Superman gets blasted by the nuclear warhead, we feel his pain, confusion, and overall vulnerability (rendered even more striking because of the grotesque way Miller draws him). His future daughter might find it pathetic, but I think there is a beautiful sort of despair in Superman’s thoughts as he begs Mother Earth for understanding towards these ‘tiny and stupid and vicious’ humans who ‘can split the very fabric of reality’ with their nuclear conflict.

While searching for sunlight stored in a flower, Superman seems to be reasoning and negotiating his commitment to his host planet and its inhabitants, conveying the sort of conflicted feelings that make for a more nuanced characterization than DKR is often given credit for.

The Dark Knight #4

In fact, even with that final fight against Batman, Superman is never entirely unsympathetic. Hell, Clark even knowingly helps cover up for Bruce’s fake death at the end!

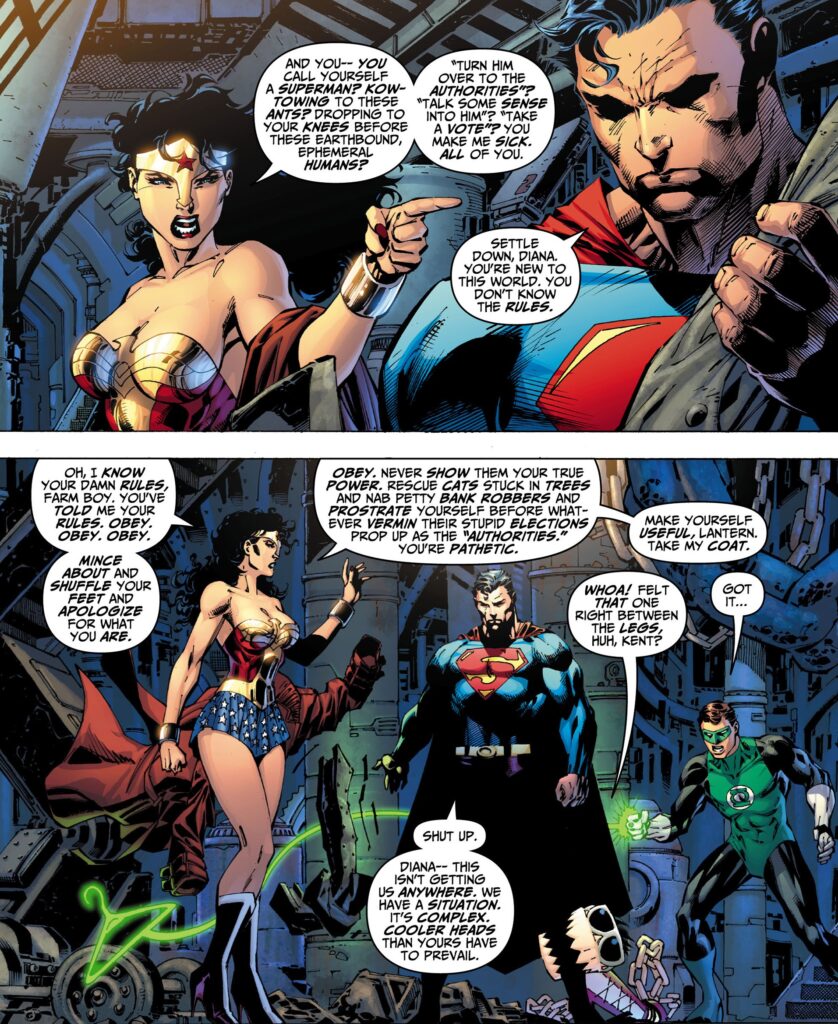

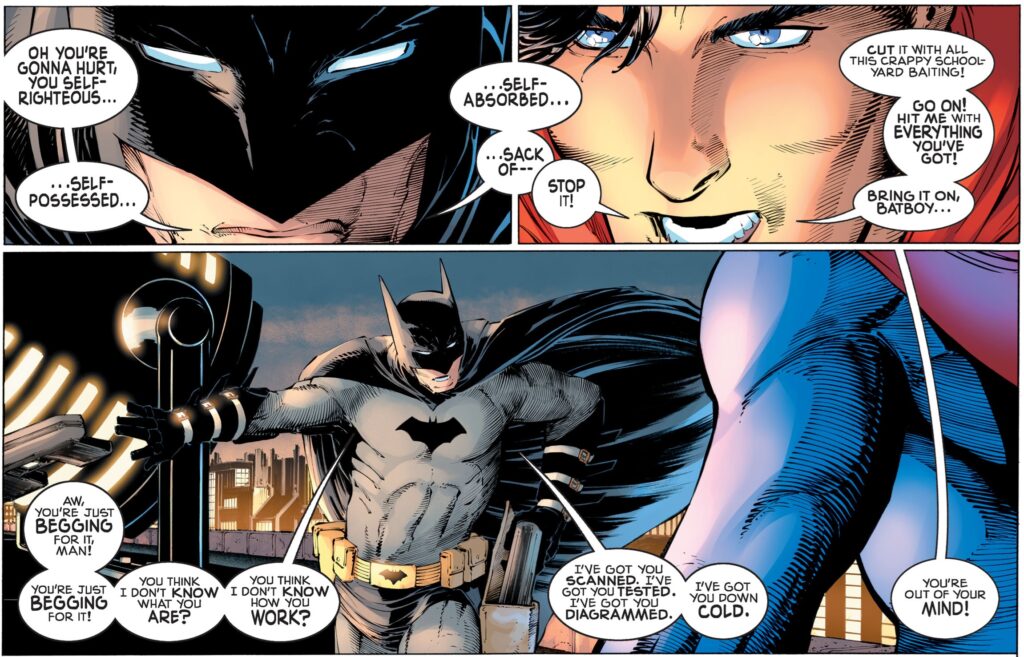

By the early 2000s, though, Frank Miller pushed Superman’s character traits so far that he almost seemed to be parodying his earlier work. If this was true of The Dark Knight Strikes Again, it was even more so in the case of All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder. In that infamous series, everyone came off like a caricature – if not visually (Jim Lee’s pencils were much more conventional than Miller’s), at least in the way they were written. So, it’s no surprise that the Man of Steel was reduced to a poster boy for blind obedience to authorities, as made explicit by (a similarly caricatural) Wonder Woman:

All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder #5

(Check out Plastic Man’s own visual mockery of Supes’ chained condition…)

As I mentioned in the last post, the critique of Superman for failing to stand up for himself was formulated from a libertarian and objectivist viewpoint, creating a facile contrast to a Batman who wasn’t ashamed to flaunt his superiority.

And yet, even a dreck of a comic like All-star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder managed to give readers the impression that there was something more hiding underneath the surface. Sure, Superman was defined – negatively – by the fact that he abdicated from using his full might and greatness… but that determined restraint also created a suggestive tension. If, on the one hand, the Man of Steel appeared to reject his own strength, on the other hand the very act of holding back required its own type of (physical and psychological) force:

All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder #5

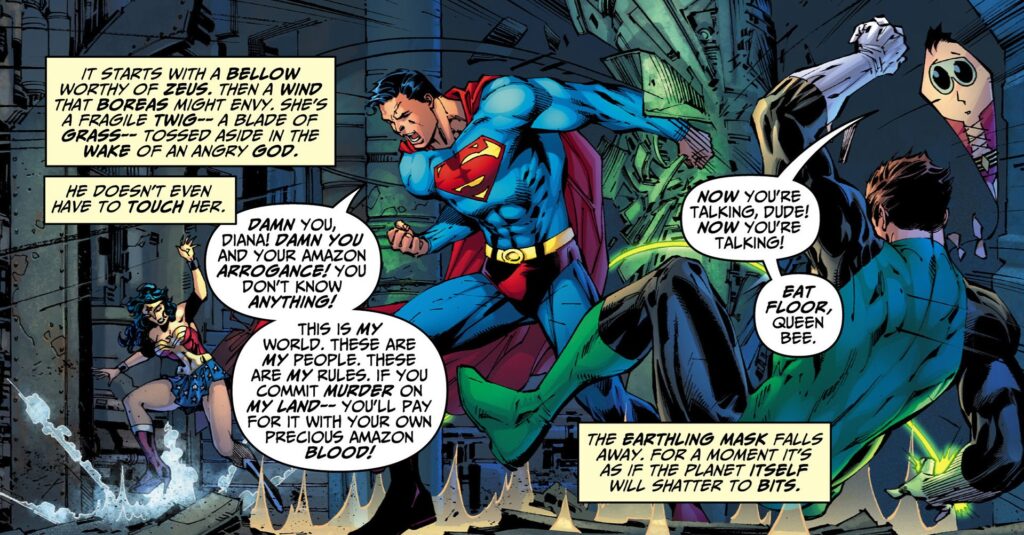

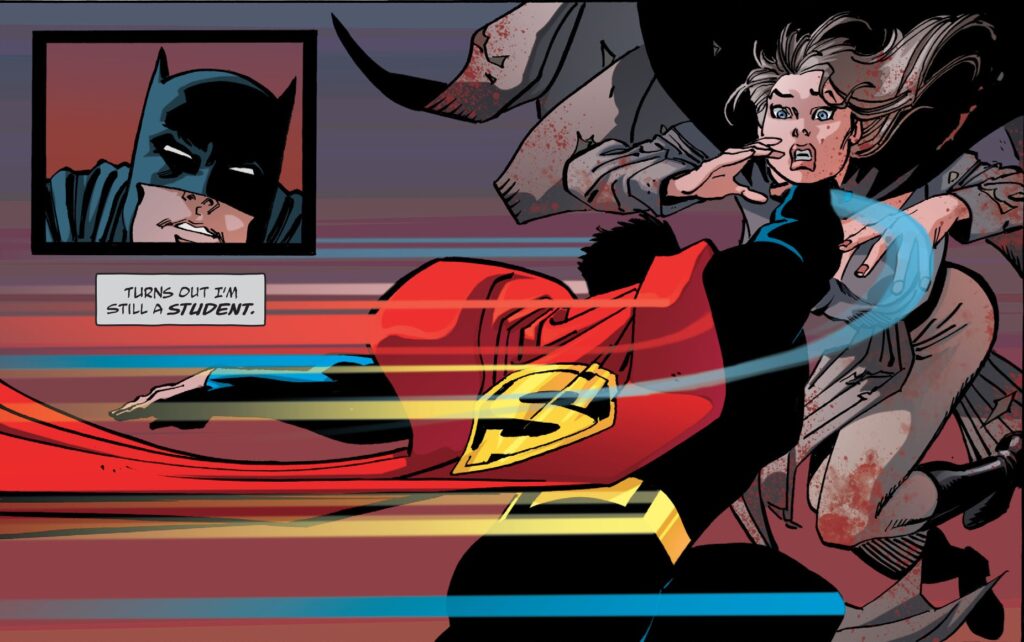

This notion paid off near the end of The Master Race, when Miller – and Batman – finally acknowledged Superman’s awesomeness. As described by the Dark Knight himself, the Man of Steel now seemed impressive both because of his ability to kick ass and because of the sense that, all this time, he had been hiding from us the true magnitude of his abilities, thus retroactively conveying a gigantic strength of will and self-control.

Drawn by an Andy Kubert trying his best to channel his inner Frank Miller, the result was an archetypical ‘fuck yeah’ moment.

The Master Race #9

Which brings us to Superman: Year One, 2019’s prestige mini-series chronicling Clark Kent’s childhood and youth, leading up to his early days as Superman. This was Frank Miller’s longest exploration of his take on the Man of Steel, properly fleshing out the motifs that he had been gradually developing for decades.

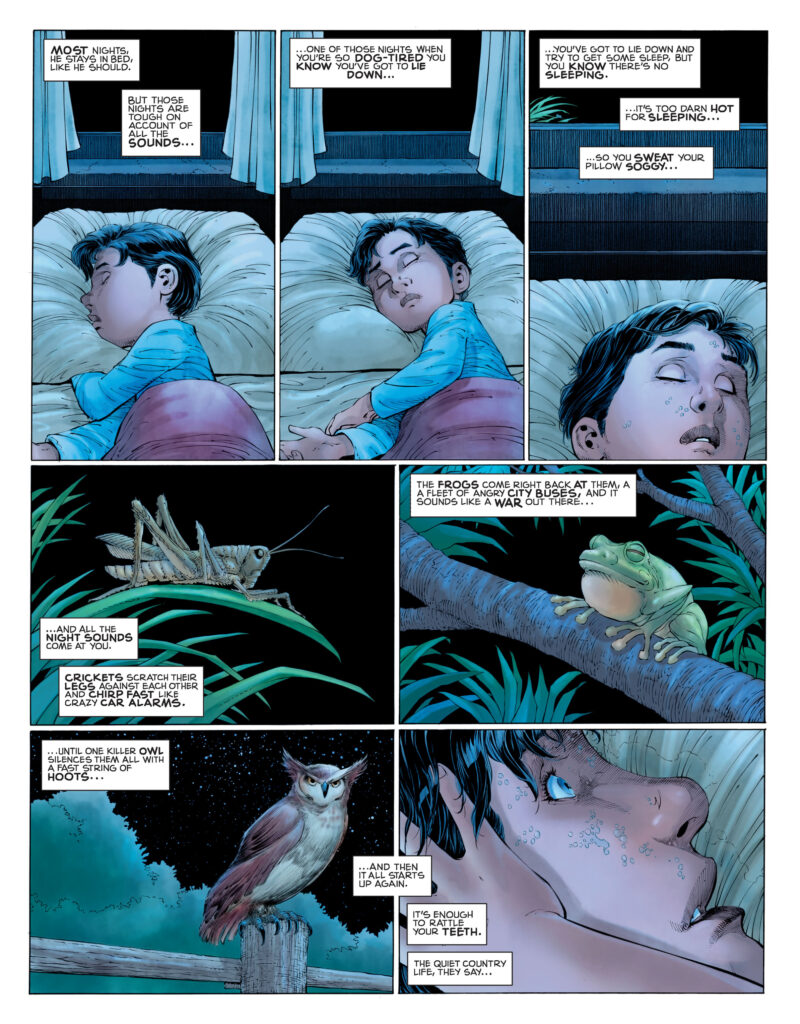

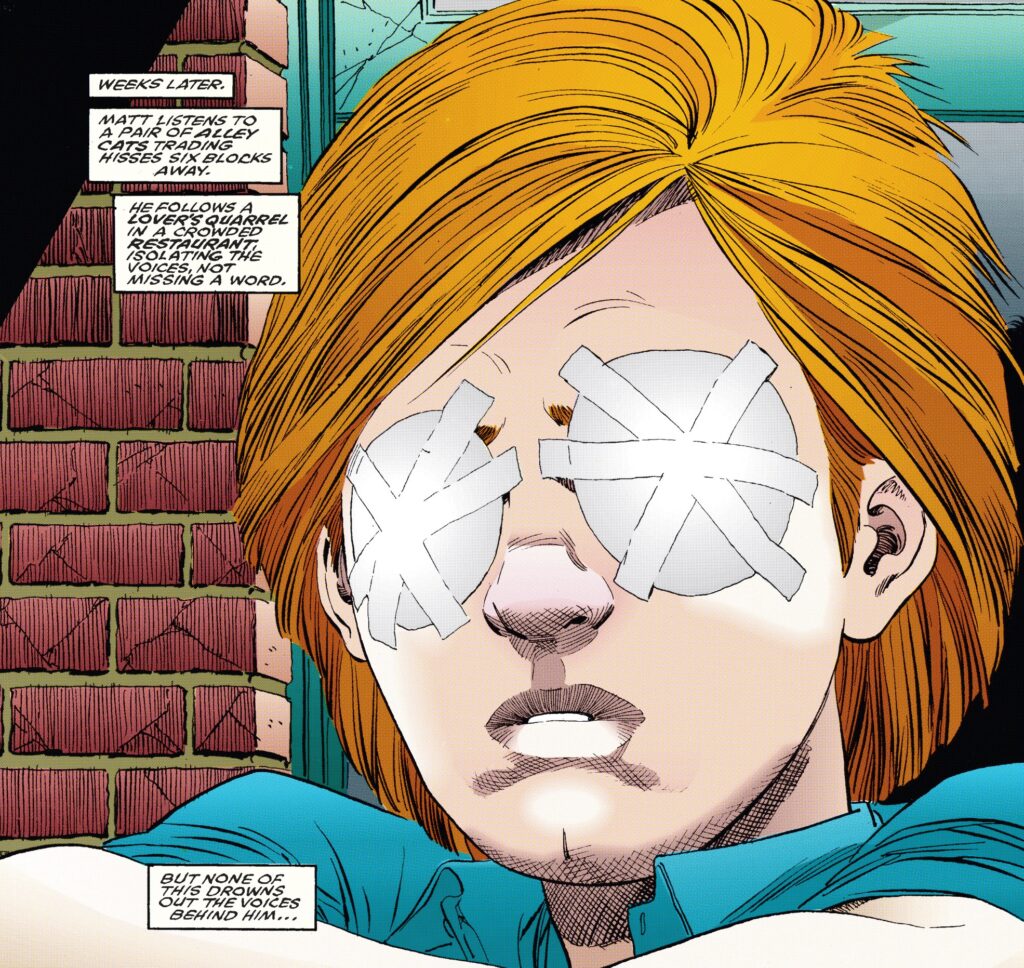

Unfortunately, it’s a pretty clunky affair: a lot of the writing is corny and heavy-handed, and I don’t much care for John Romita Jr’s artwork either. I much, much prefer Miller’s and Romita Jr’s 1993 collaboration Daredevil: The Man Without Fear, which was a more inspired reimagining of a superhero origin. In fact, even some of the high points of Superman: Year One seem like riffs on that earlier comic, such as the scenes about a young boy adjusting himself to his intrusive powers:

Superman: Year One #1

Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #1

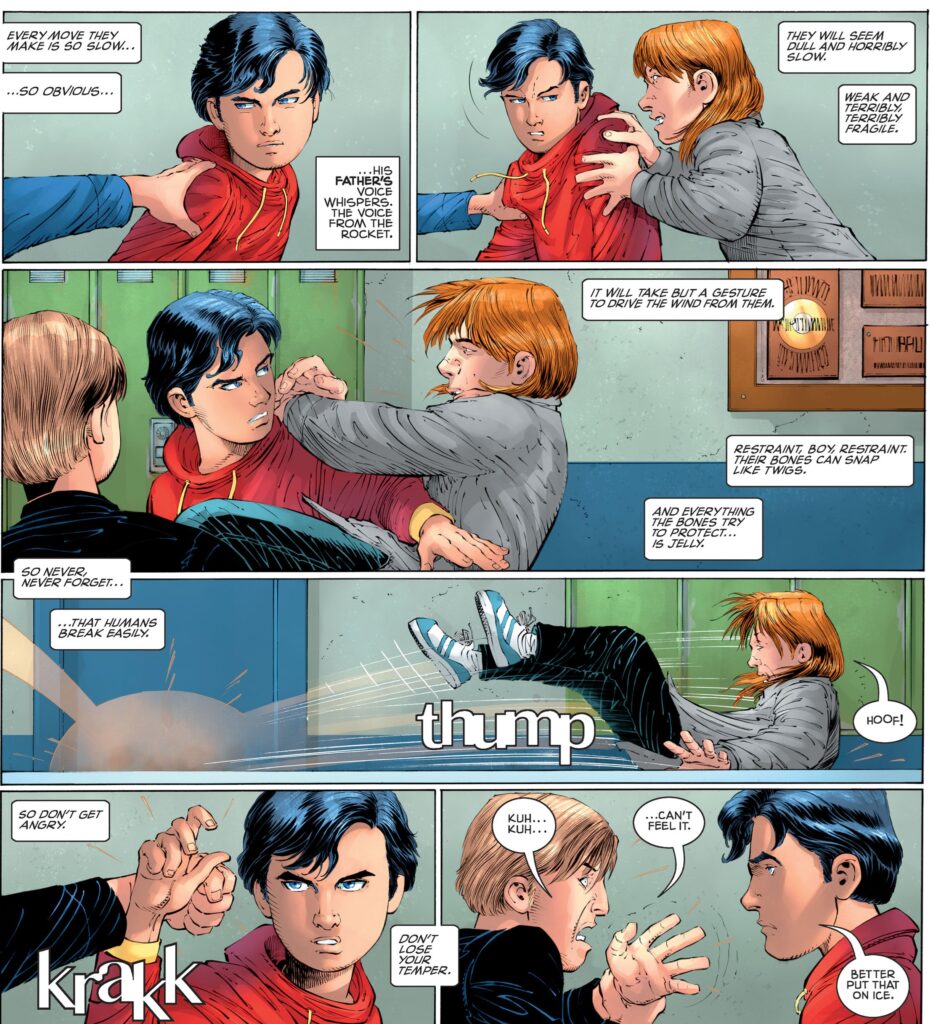

Nevertheless, we do get a deeper dramatization of Superman’s relationship with self-restraint. Clark Kent’s impulses to use his superhuman strength are counterbalanced by his mother’s liberal values (‘Nobody’s really bad, darling. Some people just get confused.’) and by his father’s pragmatic pleas for him to stay grounded (‘If you go and start thinking you’re better than everybody else… well, there’s nothing good can come of that’), although the latter also gives him an opening to act exceptionally against injustice when push comes to shove (‘First you talk to them… then you flatten them…’).

It becomes a matter of figuring out the correct strategy and proportion of force. For instance, Clark acts to prevent the gang rape of his high school sweetheart (yep), but he doesn’t kill or maim anyone. Thus, arguably, Frank Miller’s objectivist convictions give way to a more nuanced search for balance, although, in fairness, Ayn Rand’s philosophy also placed a high value on self-control (seen as a triumph of reason over emotionalism).

The first issue of Superman: Year One is ultimately a coming-of-age tale about controlling one’s body and one’s emotions…

Superman: Year One #1

It’s by issue #2 that things get weird. Even if you disregard the fact that Clark Kent hooks up with a mermaid (like he did in the Silver Age, only more so) and spends dozens of pages fighting the krakens of her incestuous father (Poseidon), you have to cope with a storyline about him joining the US Navy and learning to respect military men, who are ‘fragile’ (compared to him) but nevertheless ‘work so darned hard.’ Frank Miller even shoehorns a SEAL Team Six mission against Muslim-looking pirates (uncomfortable echoes of his Holy Terror!) before having Clark move on to less murderous conceptions of heroism…

Now, for a general Superman story, this is a terrible move. Although he was raised as an all-American farm boy, Clark is so intrinsically defined by his ethics and respect for life that it’s very hard to swallow him enlisting in the US military (except perhaps during World War II), even if driven by a curiosity to see and experience the rest of the world beyond Smallville (it’s much easier to imagine him becoming a reporter in West Africa trying to grasp the complexities of human conflicts, like in Mark Waid’s Birthright).

However, if you accept Superman: Year One as the origin of the Millerverse version of the Man of Steel (the same that shows up in DKR, etc), then I suppose this helps establish Superman’s upcoming relationship with the armed forces, as he continued to identify with their values, accepting orders in the name of the United States’ interests (including acts of war). It’s as if you took Clark out of the military, but not the military out of Clark.

Superman: Year One #2

Not that the continuity fits very smoothly… Among other inconsistencies, the future technology of The Dark Knight Returns looks rather quaint compared to the one on display in Superman: Year One, although comic book fans are used to sliding timelines, so it doesn’t require too much imagination to wrap one’s head around it.

The main connection is in terms of spirit anyway: these works speak to each other. For example, the confrontation between Batman and Superman near the end is clearly intended as a reversal of DKR’s climax, with the Man of Steel now appearing as (supposedly) more dignified and badass and the Dark Knight as somewhat pathetic and ineffective. Either that or Miller was actually taking the piss out of Zack Snyder’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, treating both characters like jerks while coming up with even more awful dialogue…

Superman: Year One #3

Batman looks particularly off-putting. I don’t mean the visual, which combines various designs (including the notorious gun holster he sported back in 1939, when Bob Kane and Bill Finger were still figuring out the character). I mean that he sounds stupid and much less cool than in either DKR or Batman: Year One… although it’s not that far from his characterization in All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder.

I suppose ridiculing the Caped Crusader (if that is indeed what Frank Miller is intentionally doing, which I’m not sure) helps make Superman less of an easy target for Batman’s objectivist voice. In turn, Miller transfers some of that voice to Superman himself, as the latter constantly weights whether to crush or to save humanity.

In other words, at the end of day, Miller turns the Man of Steel into the Dark Knight. Or, better yet, into Rorschach:

Superman: Year One #3