Like the previous installment of Gotham Calling’s mega-list of Cold War films, this week’s selection has a relatively ‘adult’ sensibility (in a non-sleazy sense), with a handful of heavy dramas about weary men and women. That said, we are now very far from simplistic binary politics, as this sample showcases the mind-bending complexity and diversity of players and ideological sub-strands that had developed by the late 1960s…

71. The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (UK, 1965)

With The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, released four years after the Berlin Crisis, the Wall makes its second appearance on this list, both opening and closing one of the grimmest spy films ever made. True to John le Carré’s literary masterwork, the East/West battle is here enveloped in an aura of frustration and disenchantment (come to think of it, the same goes for practically every entry this week).

72. Twenty Hours (Hungary, 1965)

A Rashomon-like mystery drama in which a reporter interviews various inhabitants of a small town in order to figure out why a man killed his friend eight years ago… and, along the way, uncovers a dark side of Hungary’s collectivization, where the replacement of rich landowners by local cooperatives did not prevent the development of nasty grudges and political feuds over time. The multiple perspectives and time jumps, along with the intricate structure, make Twenty Hours a somewhat challenging watch at first, but there is a steady supply of pathos, as this is (as far as I know) the first Hungarian film to confront conflicting views about the Stalinist Rákosi era, the 1956 uprising, and its subsequent repression.

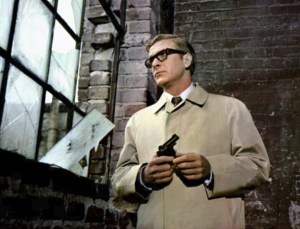

73. Funeral in Berlin (UK, 1966)

More Berlin Wall! Gone is the idiosyncratic cinematography of The Ipcress File, but the second Harry Palmer movie more than makes up for the comparatively conventional camerawork through striking location shooting, a very witty script, and the perversely labyrinthic plot – all of which take full advantage of the Berlin setting.

74. The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (USA, 1966)

When a Soviet sub accidentally runs aground on a New England island, you know you’re gonna get yet another international crisis (albeit played for laughs). It’s to the credit of The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming that it takes its time to build up the situation and develop various small-town characters and subplots before things inevitably escalate.

75. The War Game (UK, 1966)

Originally commissioned by the BBC, in this intelligent mockumentary Peter Watkins skillfully simulated the outbreak of nuclear war, including a strike on Britain. The ensuing tour de force was so distressingly authentic-looking and politically charged in its harrowing – if sometimes sarcastic – exposé of the limits of deterrence policy that the BBC ended up shelving it for twenty years (although by then The War Game had reached cinema screens and gained a cult following abroad). At the time, probably the most disturbing thing was the prospect such a future might actually come about at any moment… Watching it today, I’m more struck by the way the film recreates the past, provocatively reimagining the British as victims of the sort of actions the Allies had recently carried out in Germany and Japan in World War II.

76. Wings (USSR, 1966)

It’s almost unfair to classify Larisa Shepitko’s beautiful drama Wings as a Cold War film, as it is above all a sensitive character piece about a middle-aged school principal who looks around her ordinary life and thinks back to her heroic past, when she was a Soviet fighter pilot in World War II. Still, around the edges you can spot the generational tension, the identity crises of the ‘thaw’ era, and a culture partially stuck in the previous war. For those of us who grew up in the West, it’s also a fascinating counterpoint to stereotypical depictions of the USSR, providing a humanizing – if necessarily limited – snapshot of everyday life over there. (For my money, this is the sort of tale that could’ve worked as a perfect sequel for Garth Ennis’ and Russell Braun’s Night Witches.)

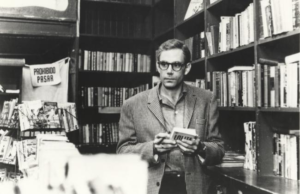

77. Billion Dollar Brain (UK, 1967)

Harry Palmer is back again, now with a mission in Finland, where a Latvian uprising is being prepared. Every film in this trilogy has a radically different tone, but Billion Dollar Brain reaches Gremlins 2 levels of absurdist reinvention (and overall absurdity, really)… The clash with expectations – along with the many offbeat creative choices – may help explain this movie’s relative unpopularity, but I’m all in for its gonzo, pop art caricature of American hawks (which still manages to look less ludicrous and dated than the huge computer referenced in the film’s title).

78. La chinoise (France, 1967)

Similarly, the French New Wave also included a number of postmodern, heavily intertextual pop art collages in which Jean-Luc Godard remixed Sam Fuller-esque pulp to iconoclastically parody right-wing politics (such as the disjointed criminal-lovers-on-the-run black comedy Pierrot le Fou and the surreal conspiracy thriller Made in U.S.A.). With La chinoise, though, Godard turned his gaze to the New Left: brilliantly anticipating the student protests of the following year – as well as the 1970s’ terrorist wave in Europe – he takes us into a quirky cell of young Marxist-Leninists who have rejected the French Communist Party and the USSR while wholeheartedly embracing revolutionary tiers-mondisme. Experimental and steeped in Maoist debates, La chinoise is also refreshingly loose, playful, and shot with the framings and primary colors of a comic book (there is even a Batman cameo!), albeit with increasingly dark undercurrents.

79. Countdown (USA, 1967)

Two years before the moon landing, the future of the space race still seemed up in air. Robert Altman’s second film was a low-key melodrama about NASA’s desperate efforts to beat the Soviets in terms of both technological achievement and public relations. Countdown is therefore a time capsule of a very specific moment of uncertainty, competition, and feeling of wide-open possibility about what lied ahead (recently, the cool TV show For All Mankind has cleverly revisited and expanded this sensation). On another level, the film also belongs to an era, sometime between 1950s’ schlock and post-Star Wars infantilization (in the best and worst senses of the word), when sci-fi cinema was taking itself more and more seriously (Kubrick famously would push this trend even further the following year, with 2001: A Space Odyssey).

80. Memories of Underdevelopment (Cuba, 1968)

A thoughtful, hauntigly melancholic gaze at the early stages of the Cuban revolution (roughly between 1961’s Bay of Pigs invasion and 1962’s Missile Crisis) as seen through the eyes of an introspective bourgeois intelectual who stayed behind while many others fled to Miami… Creatively integrating documentary footage and stream-of-consciousness editing, Memories of Underdevelopment offers not only a rich caracter study of a man’s political doubts, identity crisis, and sexual troubles, but also an original, multilayered, and superbly shot recreation of an historically significant time and place, here considered from within rather treated as a mere pawn in a larger geopolitical game.