When I chose The Department of Truth as Gotham Calling’s 2021 Book of the Year, I made a point of stressing that I still hadn’t managed to read Rutu Modan’s Tunnels, which was bound to be one of my favorite comics published last year. After all, I loved the mordant, unsentimental-yet-humanistic tone of Exit Wounds and The Property, which somehow deliver highly enjoyable narratives around grim issues (a suicide bombing, the Holocaust). Both of them seamlessly weave together intricate plotting and evolving character dynamics with several juxtaposed layers of political and existential meaning without sacrificing the story in the service of a closed-ended message.

And, sure enough, I found Tunnels yet another phenomenal book by a creator who is yet to disappoint me – and who once again mercilessly pits petty, flawed individuals against large historical processes. However, rather than analyze Modan’s habitual craft and recurring motifs (family secrets, self-absorption, unsettled national identity), today I just want to share a few impressions on what makes her latest opus stand out from what came before.

Translated from Hebrew by Ishai Mishory, Tunnels revolves around an archaeological dig in search of the Ark of the Covenant that gradually builds into a series of interconnected conflicts – and not just between Israelis and Palestinians, but also between zealots and non-zealots from both sides… not to mention the fierce competition among academics in their quests for tenure.

This premise could’ve lent itself to efforts to preach or shock, but Rutu Modan is playing by her own rules. Her approach is consistently amusing, often venturing into satire before culminating in explosive slapstick (including a flying cow). The result feels closer to the darkly comedic spirit of Elia Suleiman’s film Divine Intervention than to the somber dramatization of the HBO crime show Our Boys (to name just a couple of brilliant works about the sociopolitical tensions in Modan’s native Israel).

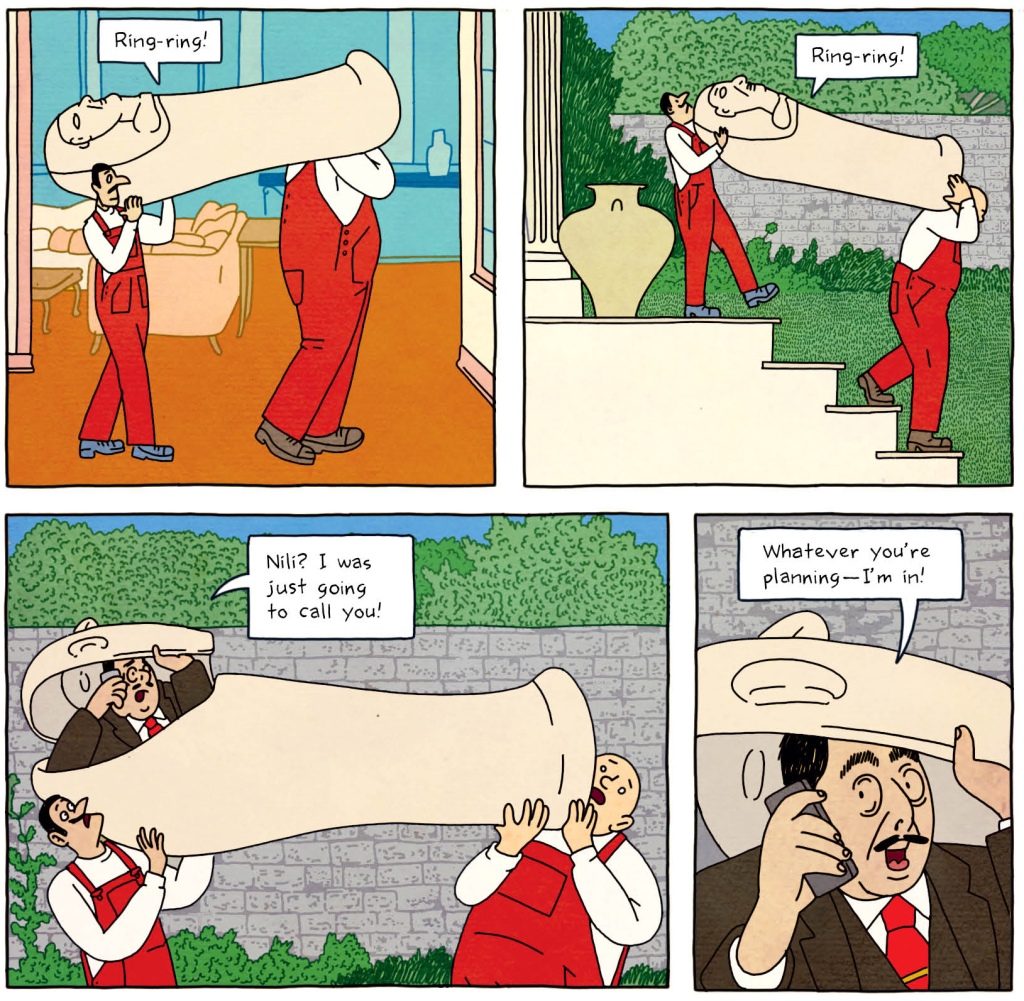

There was dry humor running through the author’s previous books – and even some outright hilarious moments here and there – but Tunnels is, for the most part, a full-on screwball farce… and a twisted one at that! No doubt drawing on her experience as editor of the Hebrew edition of MAD magazine, this time around Modan tones down nuanced characterization in favor of witty dialogue, caricatural behavior, and a cast with grotesque personalities, like the colonel who mounts a military operation as part of his sons’ Bar Mitzvah or the antiquity dealer who complains that everybody lies to him except ISIS (you can see him above, hiding in a sarcophagus for sitcom-y reasons). All the characters are despicable in some way (including Nili, the protagonist), although their depiction is typically non-judgmental.

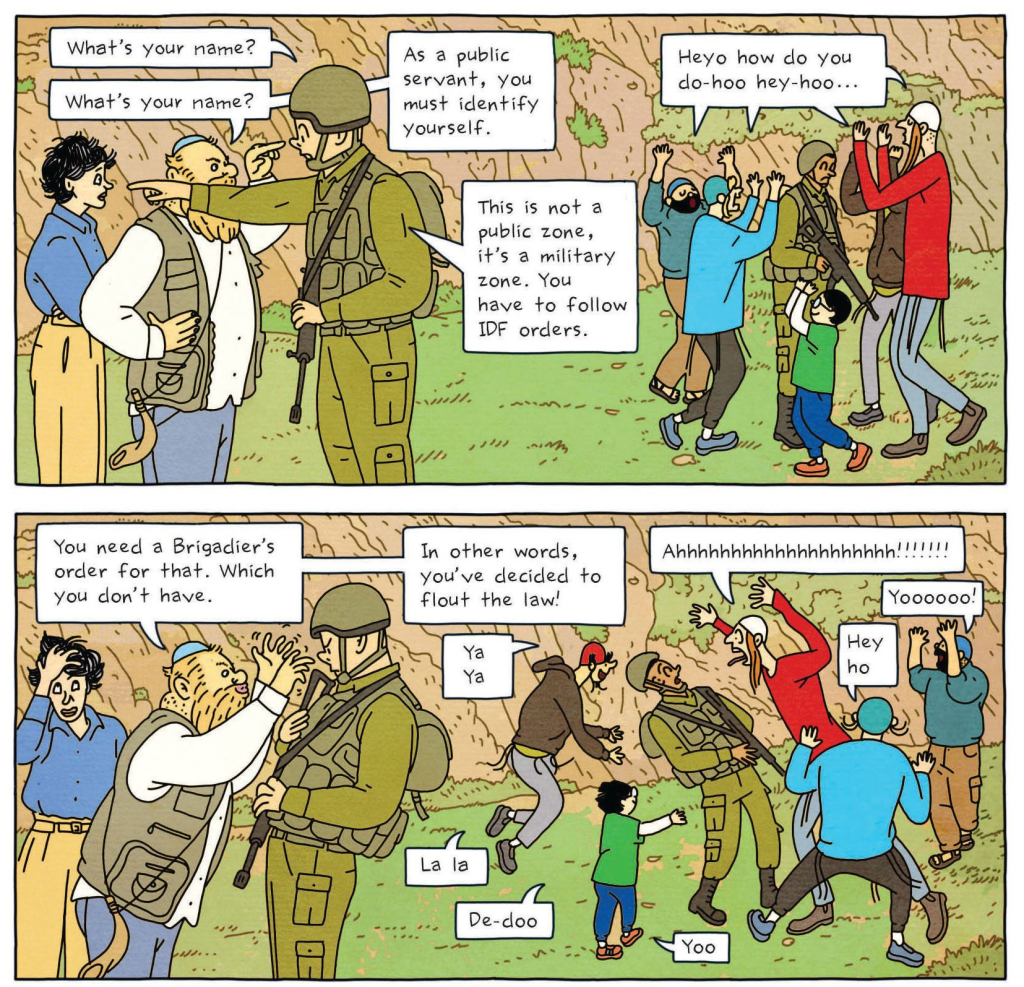

Likewise, while the art resembles Rutu Modan’s signature version of ligne claire, Tunnels is way cartoonier than its predecessors, with rounder eyes, distorted facial expressions, hairs raised in astonishment, and characters occasionally bursting into stylized tears. I wonder if this is Modan compensating for the story’s depressing setting in the Israeli-Palestinian border (making it more digestible through unrealistic visuals) or just her having a blast as she cathartically slaughters one sacred cow after another, subverting the seriousness that permeates even the most absurd ideas circulating in her country by subjecting them to overblown visual gags. It’s as if Joe Sacco suddenly decided to tackle this conflict, not through the respectful journalistic approach of Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza, but through the caustic style of his earlier, trippier comics (the ones collected in Notes From a Defeatist).

Along with the madcap designs, there’s a multilayered mise-en-scène, often staging simultaneous events in the foreground and background, thus creating a sense of constant movement and semi-chaos (as you can see in the sequence below).

Regardless, my biggest laughs didn’t come from the exaggerated drawings and rhythm, but from the *lack* of passionate reactions, i.e. from the viciously desensitized, matter-of-fact attitude with which everybody seems to deal with the violent occupation and resistance around them. It’s to Modan’s credit that, even though Tunnels is a pitch-black comedy, it never appears to go for easy shock value – the humor derives smoothly from ironic situations that play with the perversity of the real-world context, like when a gang of Zionists have to stop the construction of a settlement in order to obtain a bulldozer for Nili’s archaeological expedition.

Wild comedy isn’t the only innovation in terms of tone. Rutu Modan’s aesthetics have often been compared to Hergé’s (thus perversely reappropriating the imagery of works that occasionally traded in antisemitic stereotypes). Curiously, although Tunnels is comparatively less beholden to that pictorial style, the narrative feels much closer to Tintin’s yarns of intrigue and adventure. In fact, while Exit Wounds filtered elements of mystery and romance through a peculiar, understated sensibility – and The Property did the same for family melodrama – Tunnels comes off as much more of a pure genre piece (which is not to say you can’t hear Modan’s distinctive voice all over the material).

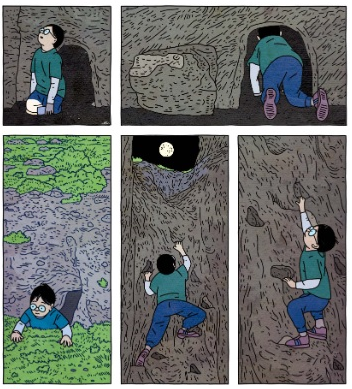

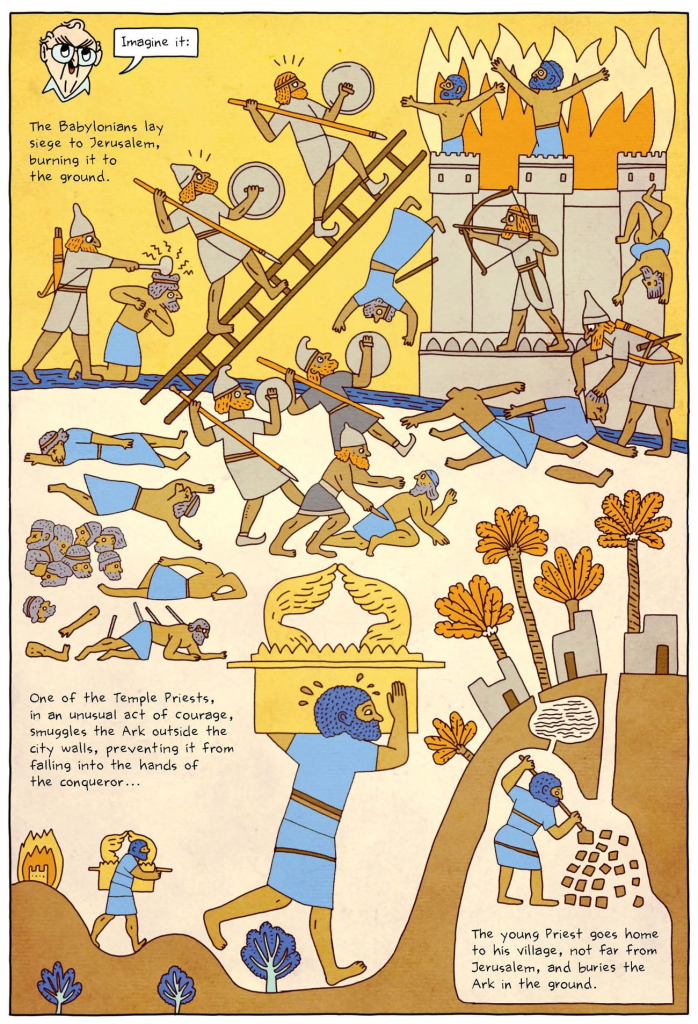

And yet, Tunnels doesn’t force an intertextual reading. There are no character types or specific set pieces borrowed from Hergé, just the *sort* of situations that could’ve been featured in The Adventures of Tintin (like the sequence in which a character ingeniously figures out a way out of a cave by drawing on historical knowledge). Likewise, Modan manages to do a whole book about people with guns searching for the Ark of the Covenant without bringing up Indiana Jones a single time. Refreshingly, her dialogue is less with western popular culture than with the myths informing the violence in her country.

When she does go for pastiche, it’s not of films or comics, but of much older illustrations:

Then, of course, there’s the politics. On the surface, the text seems uninterested in preaching for either side – it just takes racism, fanaticism, and paranoia for granted, without feeling the need to explicitly condemn or comment upon them. Rutu Modan frames most of the story from the perspective of Jewish characters, but the book is no more or less sympathetic towards them than towards the Arabs, portraying the radicals on both camps as a bunch of goofy kids.

Not that this is one of those symmetrical tales about how there’s good and evil people everywhere. Like I said, practically every character comes off as selfish and manipulative, but most of them are multifaceted, so you may end up feeling more lenient towards some members of the cast than others.

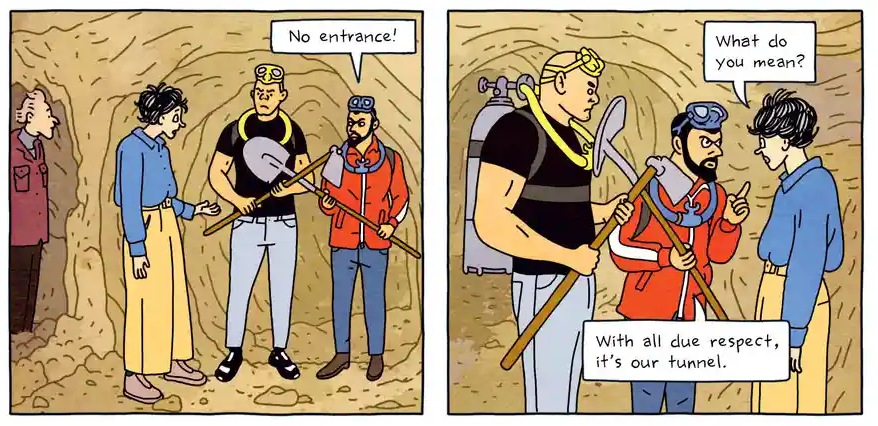

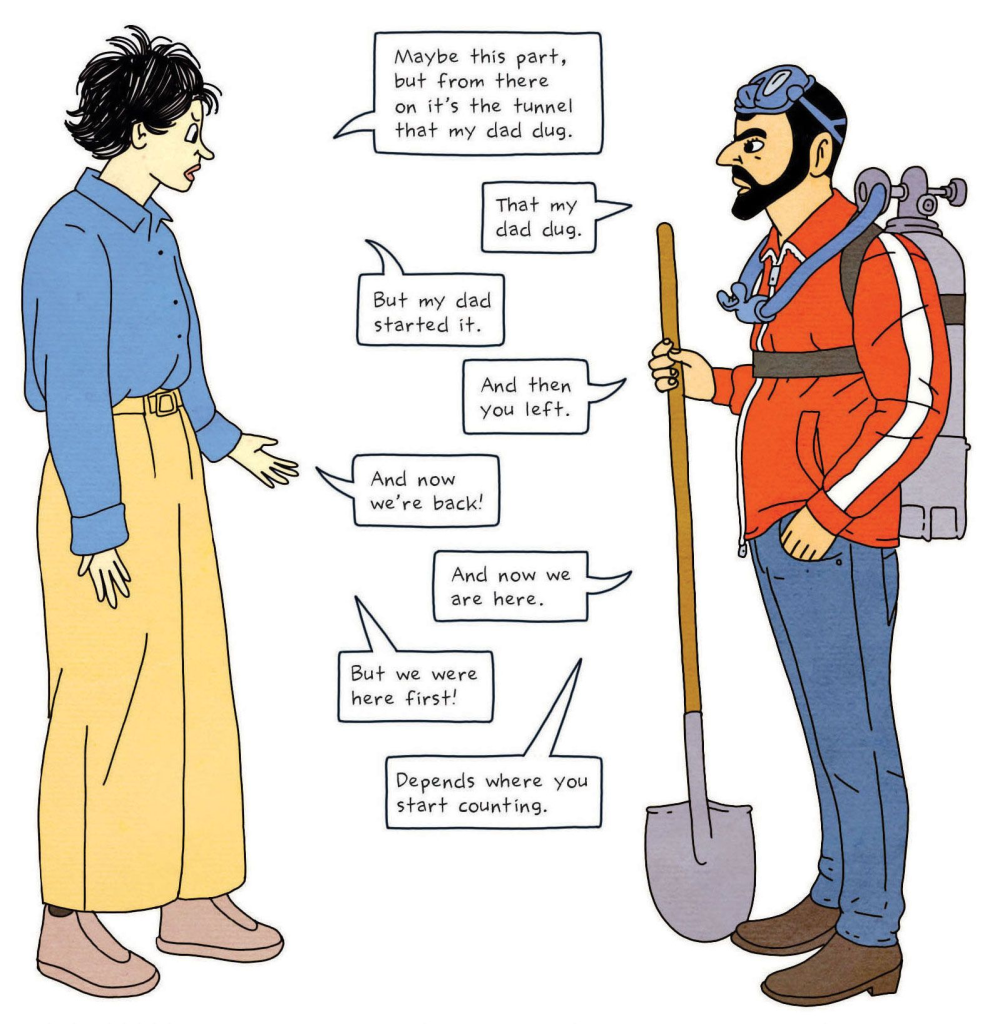

Once you start to dig (see what I did there?), you’ll find a more provocative subtext. For one thing, the whole excavation is brazenly allegorical, as the clashes over ownership of the tunnels clearly mirror the clashes over ownership of the territories above them….

The conflict over ownership isn’t reduced to this heavy-handed metaphor. Rutu Modan, who already explored the issue of property in her earlier books (most obviously, in The Property), also develops a whole subplot about a dispute for academic credit that further illustrates how subjective this topic can be. Who should claim a finding? The person who did the groundwork research or the one who turned the interpretations into books and articles? Who can own a tunnel? The person who dug it or the one in charge of conceiving the dig? And, yes, to whom belongs a piece of land? To the ones who occupied it first, most recently, or the longest?

The thoughtful afterword expands on the book’s themes, interestingly bridging them with those of The Department of Truth (which, I guess, denotes my own interests). Against today’s general loss of agreement over reality, exacerbated in the pandemic, Modan proposes more fiction that doesn’t claim to tell the truth – unlike the stories feeding religious strife in her region – but which instead tries to suture the narratives of different peoples into complex, turbulent plots full of contradictions and characters that do both terrible and wonderful things. After all, as any comic book fan knows, conflicting stories ‘can happily coexist in our brains,’ even if they haven’t always been able to coexist in the material world.