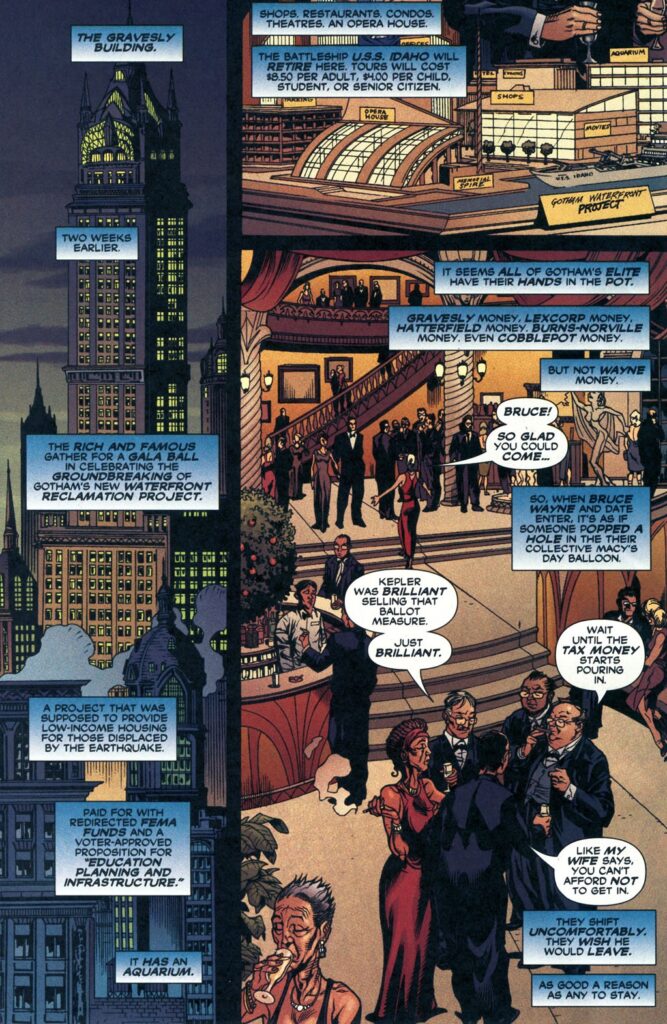

Detective Comics #801

Political thrillers are one of my favorite genres. I crave witty, cunning characters and intricate plots that combine micro and macro scales while turning the political process into thrilling suspense and clever maneuvers, both because it’s a way to reflect about norms and institutions and because of the appealing fantasy for every nerd (like me) that rhetoric can be a powerful weapon.

In the 21st century, we’ve been spoiled for this genre, in part due to The West Wing’s success and influence. Not all of the recent entries were as well-written as Aaron Sorkin’s seminal TV show, but plenty of them were, from the Nordic hit Borgen (whose latest season is a fascinating treaty on colonialism) to this year’s The Diplomat, not to mention acclaimed dramatizations of lobbying on the big screen, such as Miss Sloane and Thank You for Smoking. Crucially, the sharp satire of Armando Iannucci’s films (In the Loop, The Death of Stalin) and shows (The Thick of It, Veep) has paved the way for the corporate black comedy of Jesse Armstrong’s Succession (which dabbed into high politics a number of times, especially towards the end of the final season) as well as the more lighthearted EU sitcom Parlement. Iannucci’s work actually joins a long lineage of superb takes on the genre by British television, which probably hit the peak of cynicism back in the 1980s with the spy series The Sandbaggers and the sitcom Yes, Minister. In turn, Dahvi Waller’s Mrs. America revisited the 1970s’ political scene in the US with an original perspective that made it one of the most enjoyable shows I binged during the early pandemic.

More recently, I was pleasingly surprised to find out Oppenheimer, after many detours, eventually settles into one hell of a political thriller about the origins of the Cold War. Christopher Nolan’s take on communism isn’t particularly sophisticated (a good joke about ‘Property is theft!’ is botched by mixing up Marx with Proudhon), but it works fine as a story about anticommunism – with the added meta-twist of assigning the cinematic Tony Stark a pivotal role in the escalation of the arms race!

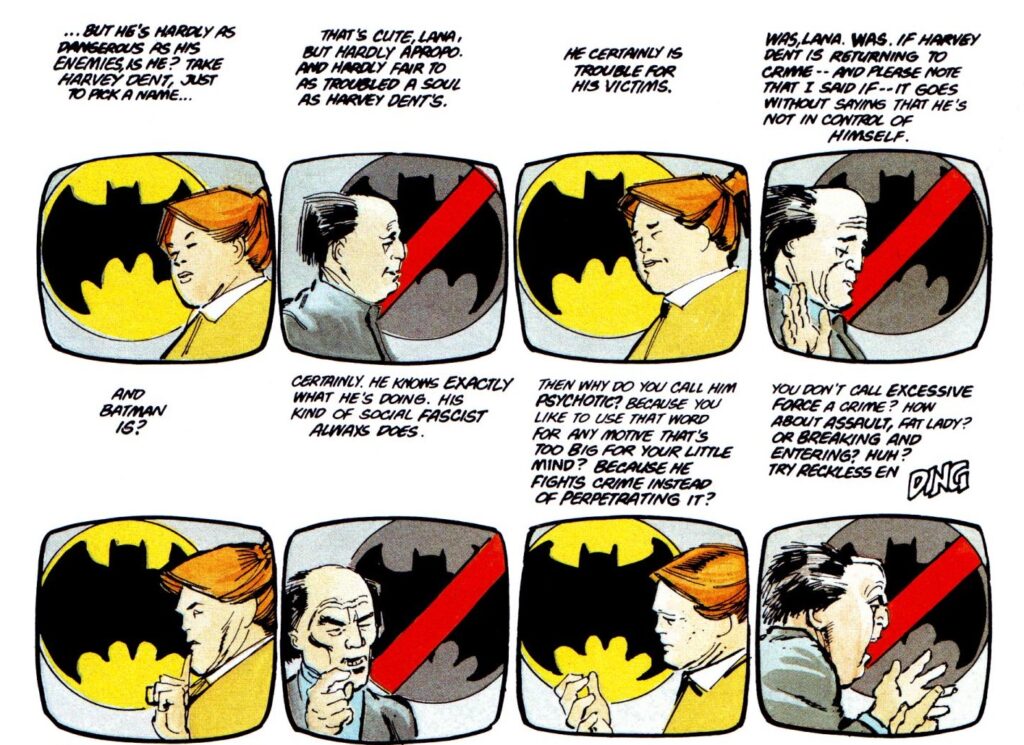

The Dark Knight Returns #1

In comics, the genre is not as popular, probably because its reliance on arguments as the main driving force begs for a ‘talking heads’ format that is usually not very appealing for either readers or creators. Sure, there are remarkable exceptions. Famously, Frank Miller got away with exchanges like the one you see above by innovatively (at the time) reproducing the visual language of television debates. Abel Lanzac’s and Christophe Blain’s Weapons of Mass Diplomacy kept the artwork pleasingly dynamic and amusing even as it delved, with impressive authenticity, into the French Foreign Ministry at the dawn of the War on Terror. Also from France, The Death of Stalin started out as a comically caustic graphic novel by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin, who followed it up with Death to the Tsar, an equally loose fictionalization of the 1904 assassination of the Governor of Moscow, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich. If Stalin trades on grotesque caricature, Tsar is more of a grim character piece, but they both make the intricacies of 20th-century Russian politics outrageously entertaining by shoving in as much violence as they can get away with.

For the most part, the solution has been to hybridize, merging the key features of the political thriller with the visuals and tropes of other traditions of comic book fiction without necessarily sacrificing the former’s relevance and intelligence. Thus, Greg Rucka, after doing his own spin on The Sandbaggers with Queen & Country, satisfyingly blended the genre with superheroes in his runs on Wonder Woman and Checkmate. Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris pulled off a similar trick in Ex Machina, albeit shifting the focus from international diplomacy to city politics.

Which brings us back to Batman comics…

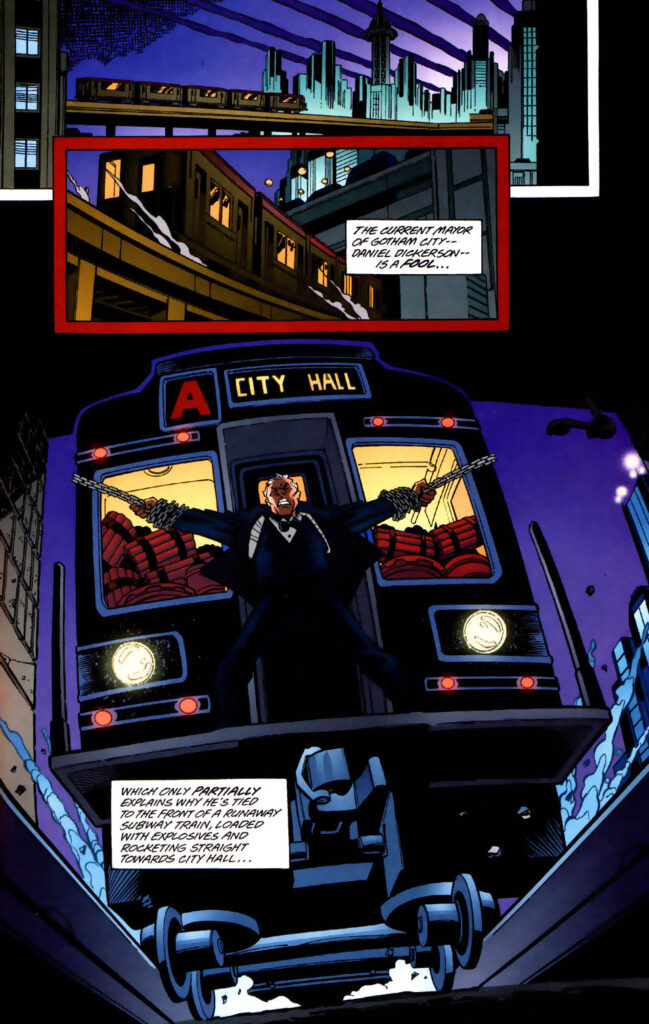

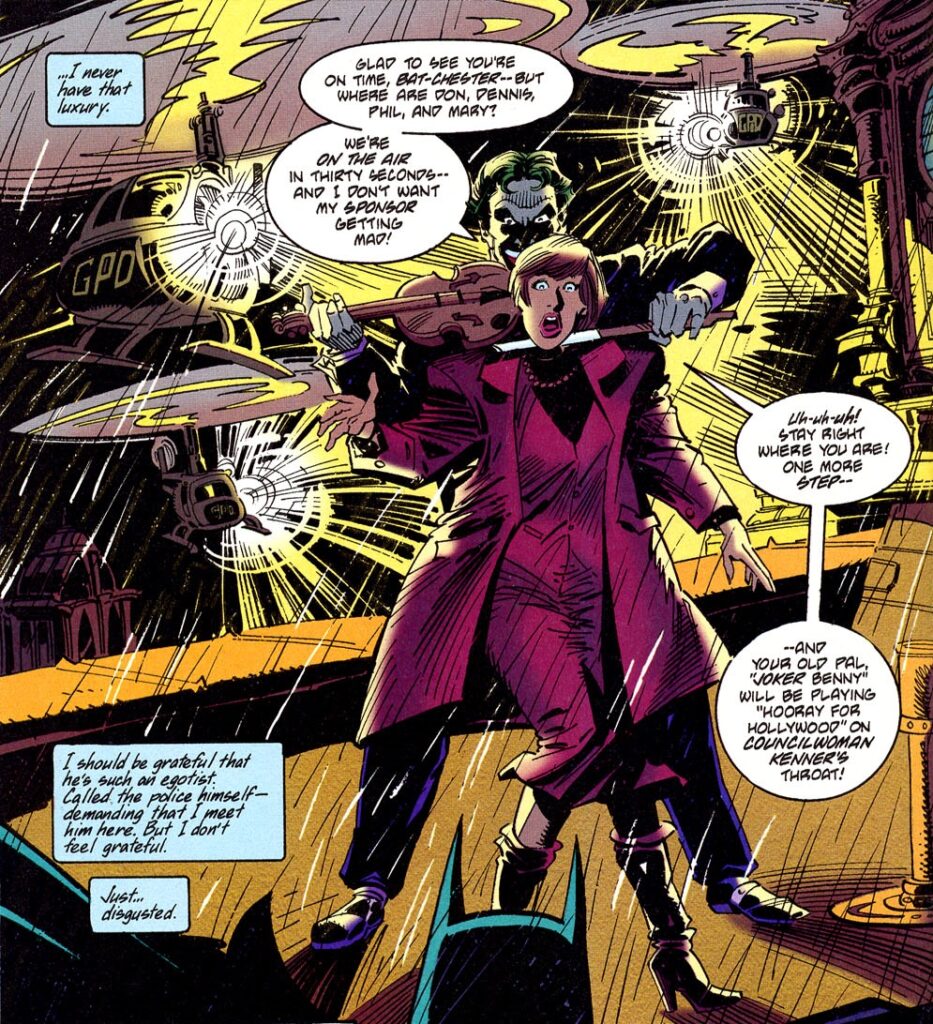

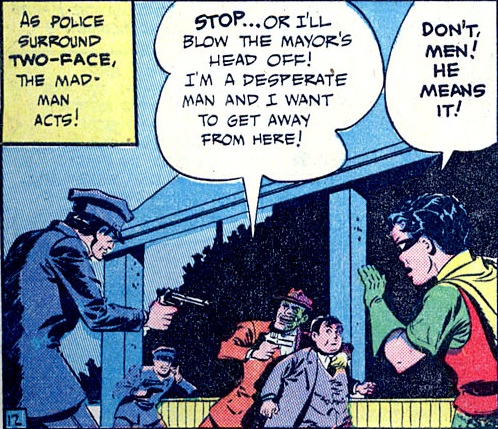

Batman #602

My favorite Batman comics tend to be anchored in Gotham City and to flesh out this grim-yet-colorful place, including by paying attention to the local political scene… On the one hand, the fact that politicians have to constantly work around – and respond to – Gotham’s surreal criminals (and surreal crimefighters) can produce moments of highly creative speculative fiction, not to mention outright satire. On the other hand, the zany schemes of rogues like the Joker or Two-Face have repeatedly targeted City Hall and adjacent institutions, assigning them a key role in the plot.

Legends of the Dark Knight #68

In particular, there is a long tradition of tales revolving around electoral campaigns (a trope that Matt Reeves also worked into the 2022 movie The Batman), even though, when you think about it, it’s pretty odd that you still have candidates eager to get elected. After all, Gotham City’s politics have a preposterously high mortality rate. If you’re the mayor, you can be certain that, sooner or later, at least one goofy maniac is bound to come after you…

Detective Comics #68

Catwoman (v2) #93

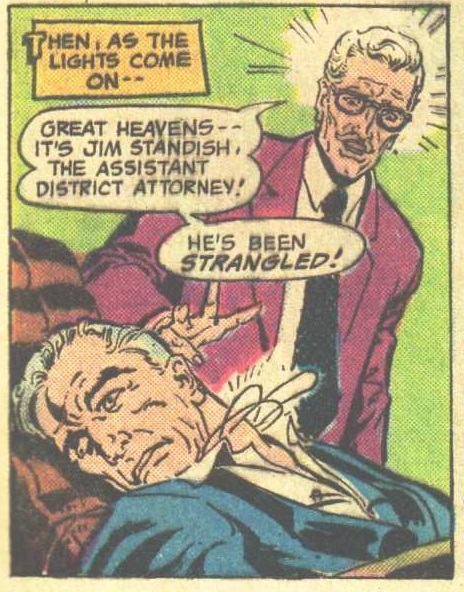

… and it’s not just the mayor! Police Commissioner James Gordon can fill a whole multivolume encyclopedia with all the assassinated officials he’s seen over the years.

Batman #270

Batman #419

The answer as to why politicians would actually risk this fate must be found in another defining feature of Gotham: the entire city appears to be so shamelessly and structurally corrupt that the risk must pay off, somehow!

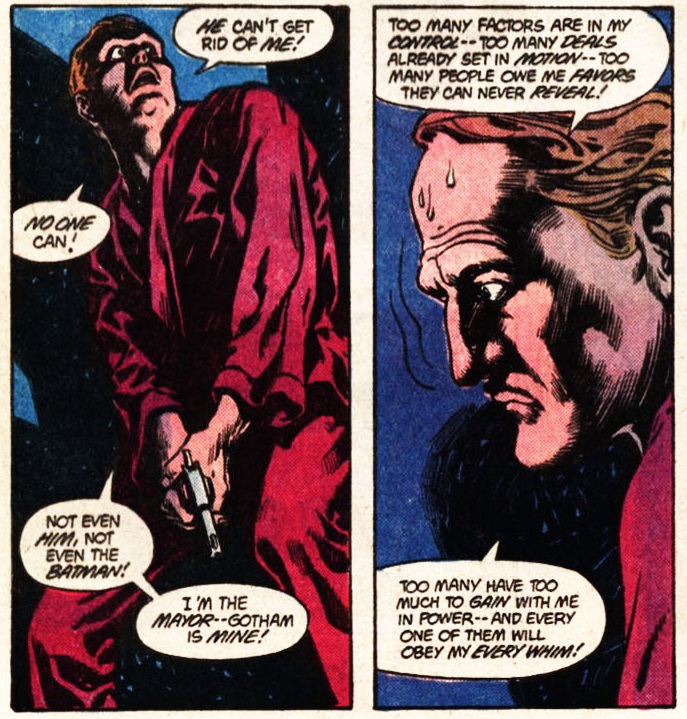

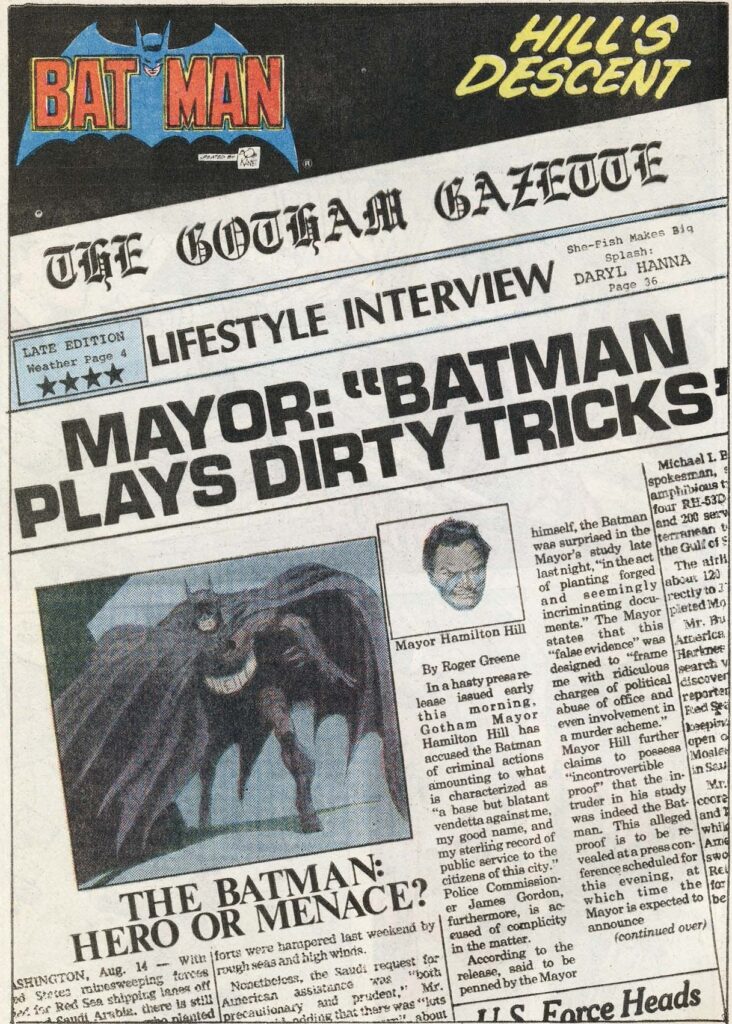

Consequently, at their best, Batman comics have developed running subplots that – especially when read in relative isolation – feel like veritable political thrillers as they show all the backroom deals and power games that exploit the city’s eccentric terrorism, street violence, and white-collar crime. For instance, back in the early 1980s, writers Gerry Conway and Doug Moench got a lot of mileage out of this, devoting plenty of pages of Batman and Detective Comics to the fraudulent and manipulative machinations of the incredibly shady Mayor Hamilton Hill. This was full-on political thriller territory, with constant plot twists and multiple characters pursuing their own agenda (including the Dark Knight, of course), gradually driving Hill over the edge:

Batman #378

Mayor Hamilton Hill finally fell from power in 1985, when his latest smear campaign against the Caped Crusader ultimately backfired.

Detective Comics #546

That’s right, Gotham will put up with corruption and abuse of power, but don’t mess with the Bat!

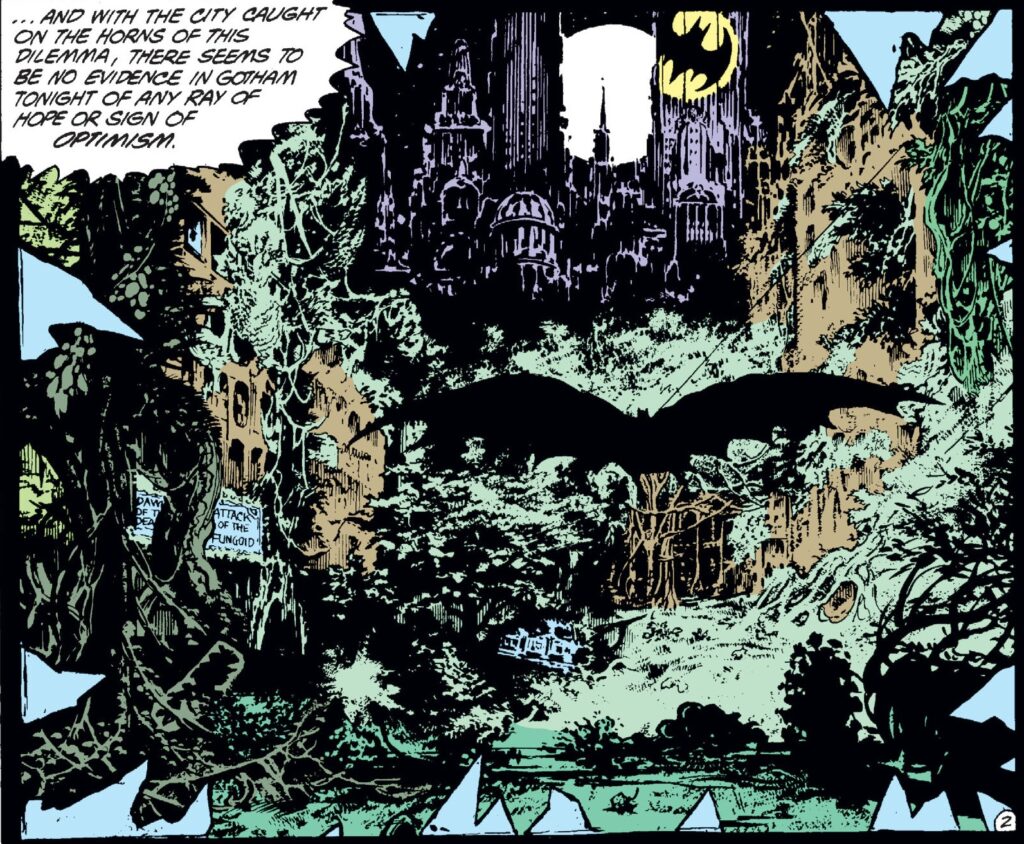

Hill was replaced by Mayor George P. Skowcroft, who for once was more incompetent than crooked… which was nevertheless quite unfortunate, given that he had to deal both with the multiversal cataclysm known as Crisis on Infinite Earths *and* with that time a vegetable god took revenge on Gotham for the arrest of his lover by turning the city into a jungle:

Swamp Thing (v2) #53

The latter storyline may appear to be less informed by politics than all those previous shenanigans involving Hamilton Hill. However, bear in mind that the story took place during Alan Moore’s classic run on Swamp Thing, where it closely followed the ‘American Gothic’ arc, which belongs to this whole subgenre of politically charged comics written by British creators delivering extensive tours of US social issues (similar examples are Pat Mill’s ‘The Cursed Earth’ arc on Judge Dredd and the entirety of Garth Ennis’ Preacher). In this case, when you think about it, the main villain of the piece is the judicial system’s puritanism, to the point that the tale’s resolution hinges on an exchange of legal arguments between Batman and Mayor Skowcrof.

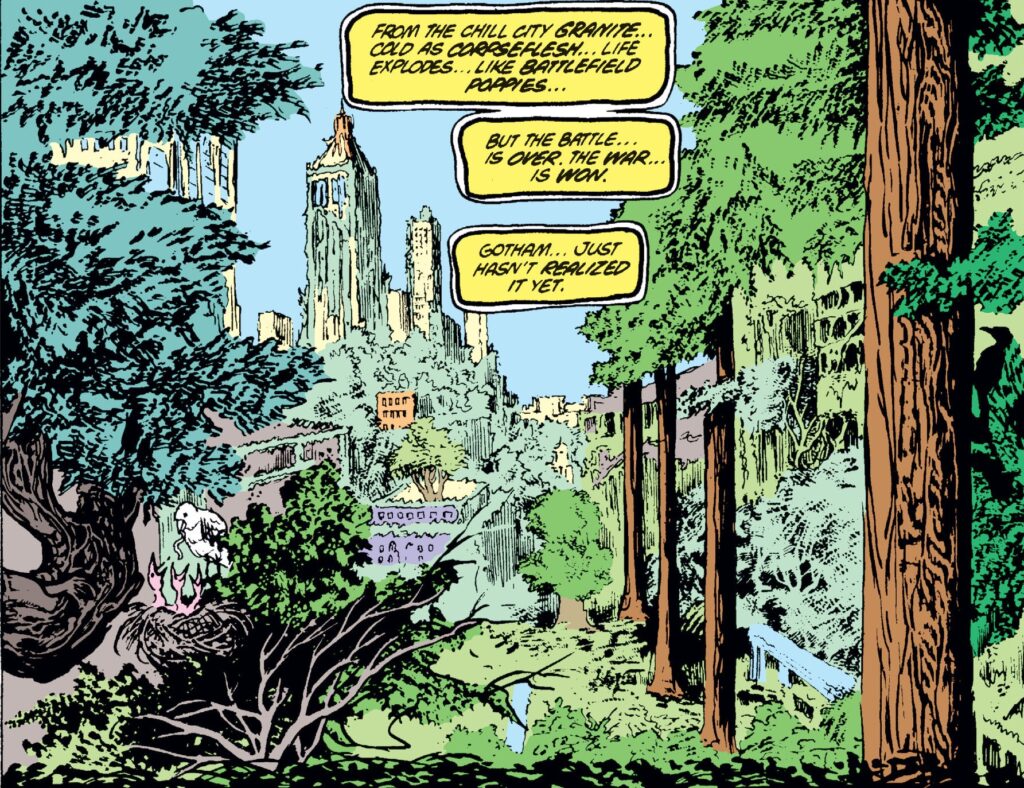

Plus, you can tell the post-hippie anarchist Moore had a blast imagining wild nature literally destroying the urban modernity of American civilization:

Swamp Thing (v2) #53

(Yep, for all the talk about recent pop culture breaking conservatives’ brains, superhero comics have been pretty political for quite a long time…)

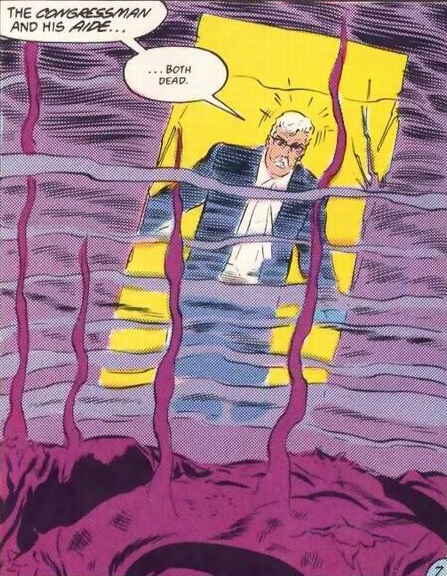

For a while after this, the parallel stories of Gotham’s authority figures largely disappeared from the comics. Mayors and other city officials would sometimes feature more or less prominently, but there tended to be little continuity across issues… In fact, more often than not, politicians served as cannon fodder for the villain du jour, so that their gruesome deaths practically became a running gag.

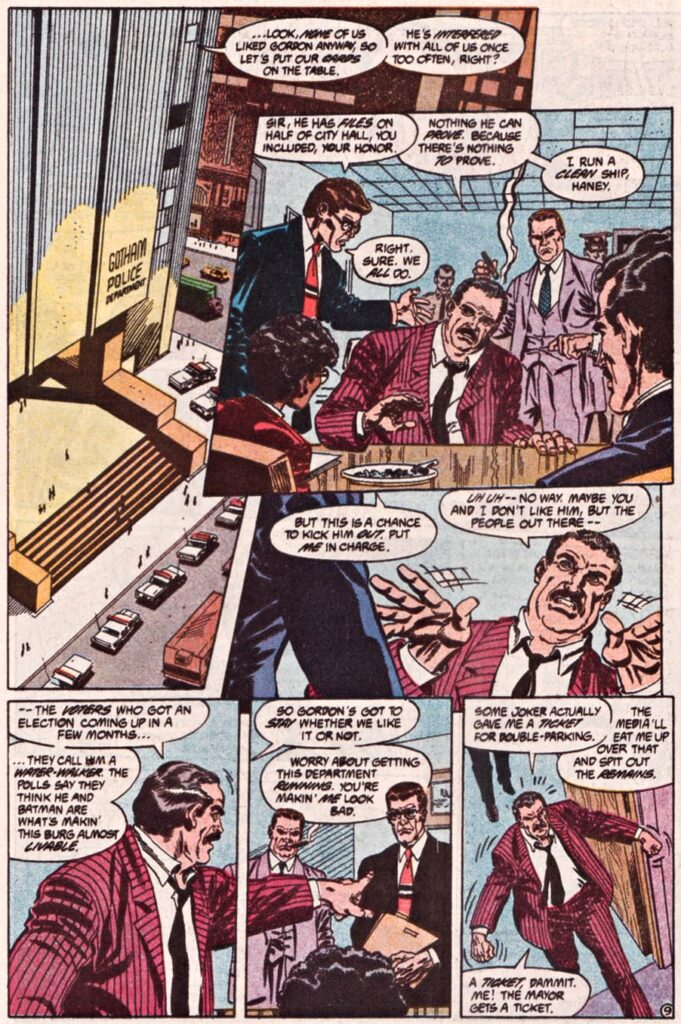

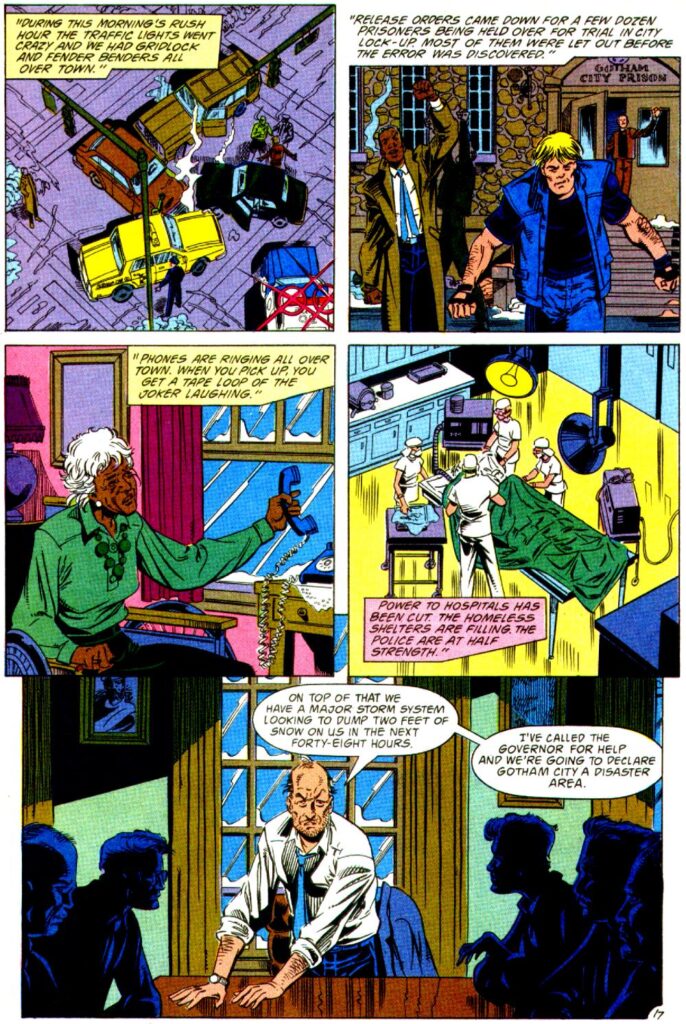

This is not to say that you didn’t have occasional moments that could fit into an episode of House of Cards or into the third season of The Wire. For instance, here is Deputy Mayor Harriman, in 1990, running a crisis meeting soon after Commissioner Gordon had a heart attack:

Detective Comics #626

Harriman sounded like a promising character, but unfortunately we didn’t see him again.

A year later, by the time the Joker took over Gotham’s computer system and demanded a ransom of one billion dollars in cash, Harriman had clearly been replaced – either that or he had drastically changed his appearance. In any case, the latest mayor didn’t last long either… Since the Caped Crusader was out of town at the time (in Rio de Janeiro), within a few pages chaos broke loose all over the city, driving yet another mayor to the brink of sanity:

Robin (v2) #3

As I’ve mentioned a bunch of times before in this blog, under the group editorship of Denny O’Neil, throughout the 1990s Gotham City became a much more cohesive setting. And, sure enough, fans actually grew familiar with the strategies and policies of successive mayors, district attorneys, and police commissioners… The campaigns and elections of 1992 and 1995 got plenty of coverage on the pages of Batman, Detective Comics, and Shadow of the Bat, sometimes unfolding in the background while the Dynamic Duo fought the Ratcatcher or Killer Croc, other times jumping to the forefront – and in any case gradually furthering the kind of worldbuilding that enabled successful crossovers where the city itself (including its administrative institutions) gained a center role, with Gotham assailed by an epidemic in Contagion and an earthquake in Cataclysm.

I loved all of this. As a teenager, I thought I was getting insight into a grown-up world: not only did my comics seem more complex, adult, and imbued with authenticity (and therefore, I assumed, sophistication), but they teased a future in which I would also come to understand and care for real-life political games. Today, revisiting these issues, I find in them fascinating insights about the past: both about my own past (seeing how they informed views and tastes I later developed, such as my passion for political thrillers) and about a political zeitgeist, as, although fictional, Gotham tales convey dated notions and buzzwords along with an occasional sense of continuity and familiarity:

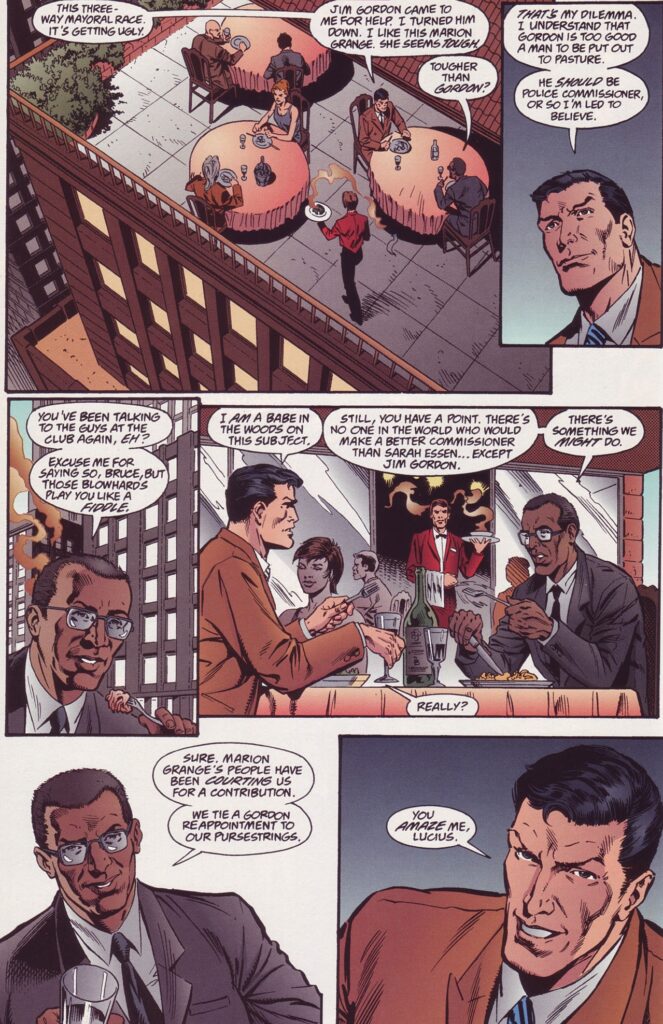

Detective Comics #689

The scene above (a classic bit of Bruce Wayne manipulating those around him with his fake persona and using even his non-Batman resources to get his way) was penned by Chuck Dixon, one of the writers who felt most at home combining smart entertainment with macho fantasy, regularly churning out the comic-book equivalent of ‘90s Dad Thrillers. You can attribute this attitude to a degree of cynicism stemming from Dixon’s notoriously conservative politics, but I actually think it has more to do with his background as a genre journeyman heavily influenced by Golden Age Hollywood, where it was not unusual for stories to work on multiple levels for differently aged audiences. Dixon’s knack for figuring out the precise appeal of each type of story and thoughtfully executing the various beats with careful attention to plot, pace, and characterization was thus put in the service of narratives that openly echoed classics like Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

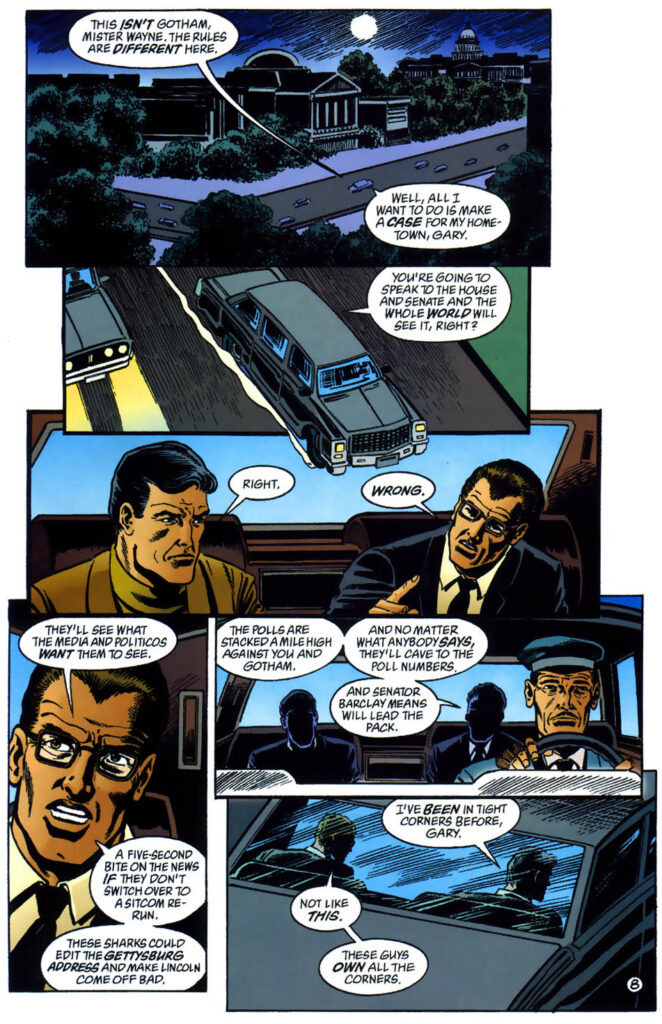

Hell, after the quake, Dixon actually had Bruce lobby for support for Gotham in Congress, in a 3-part arc called ‘Mr. Wayne Goes to Washington.’

Batman #560

(Notice how, without calling too much attention to itself, Jim Aparo’s artwork injects dynamism into an extended dialogue scene by constantly framing it from new angles… Besides preventing visual boredom, this also helps ground the scene’s geography. Plus, because Dixon’s script set the scene in a car, you get an additional sense of action progression.)

Since even the Dark Knight can only do so much against Washington, Gotham City actually ended up cut out from federal aid for a year, during the No Man’s Land crossover event. In 2000, when Gotham was finally rebuilt, editor Denny O’Neil did an excellent job of laying out how the process would develop, politically and sociologically, with the various Batman-related series featuring tales about real estate deals, urban renewal, zoning regulations, and property disputes between the returned citizens who had left the city during NML and those who had stayed behind. Writers like Devin K. Grayson, Bronwyn Carlton, and Greg Rucka actually managed to pull off some very cool yarns that neatly combined this local politics angle with the sort of thrilling action and weird crime you’d expect from a Batman caper.

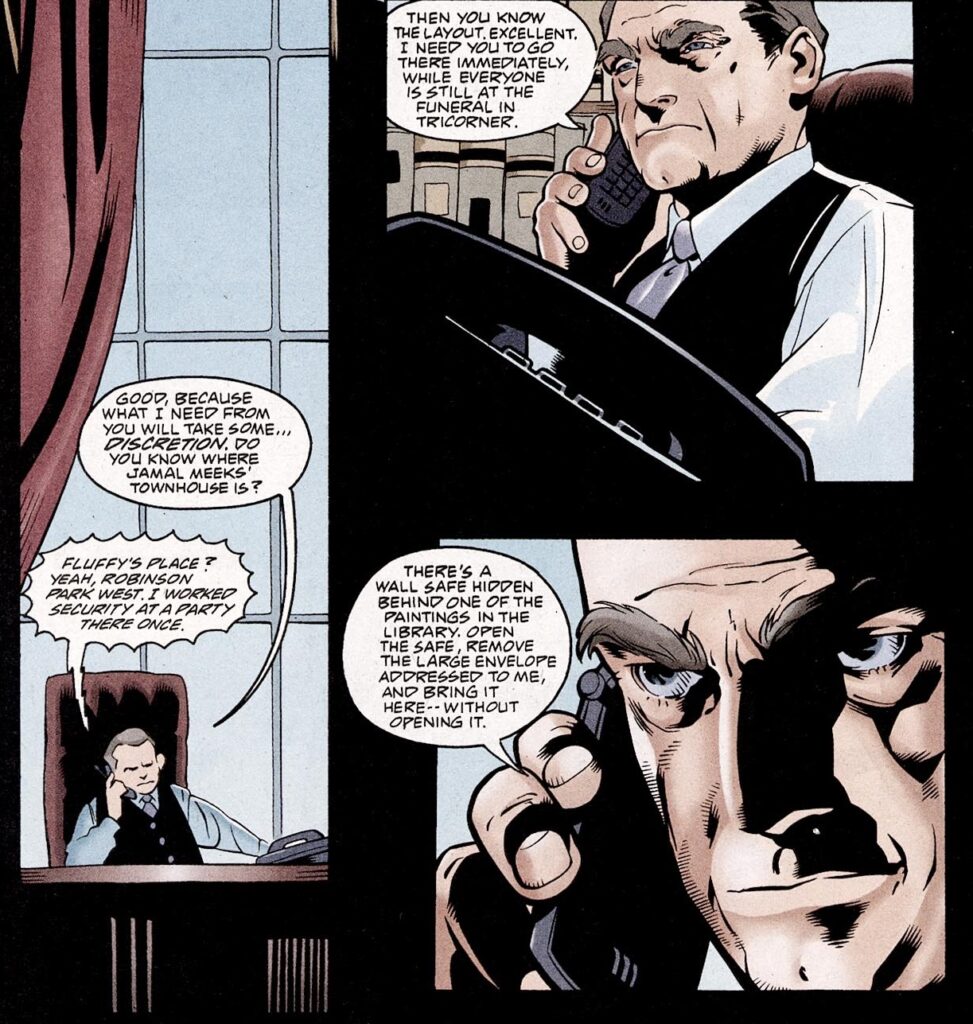

Many of these comics featured the appropriately named new mayor, Daniel Dickerson, who – even for Gotham standards – was an entertainingly dishonest and despicable dick…

Catwoman (v2) #86

Mayor Dickerson became a regular foe on the pages of Catwoman, where he got routinely humiliated and blackmailed. (And his wife Amanda turned out to be quite a character as well!)

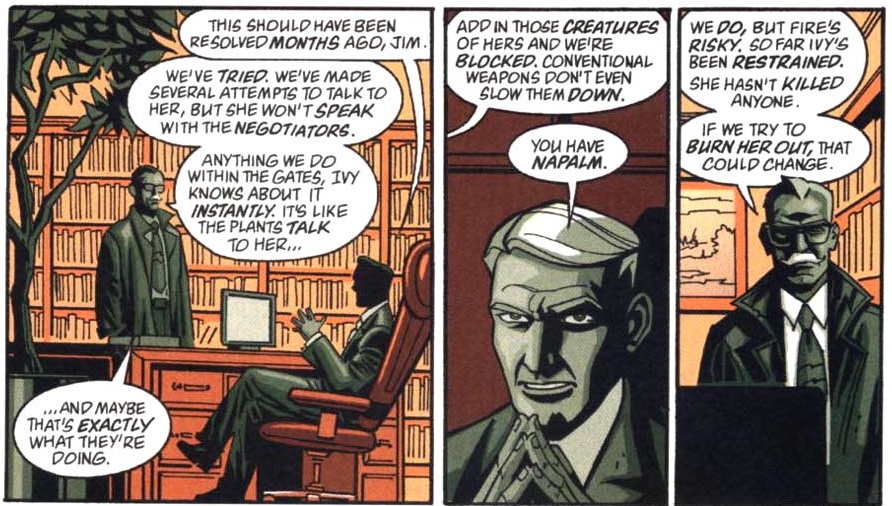

Greg Rucka also had a field day with Dickerson in Detective Comics, where one of the running themes was the boiling resentment against those who had abandoned Gotham, epitomized by the mayor himself. Notably, Rucka showed us how the authorities dealt with all kinds of challenges of the post-No Man’s Land transition, like the fact that Poison Ivy had taken over the city’s main park and now continued to occupy it with the help of some plant creatures and a cult of teen followers:

Detective Comics #751

(I really like the subtle way the characters ‘act’ through their eyes and hands, but Shawn Martinbrough’s mise-en-scène here is much less imaginative than Aparo’s example I highlighted above… By largely falling back on a shot/reverse shot pattern, much of the scene is carried by Rucka’s dialogue. That said, I love the silent punchline in the final panel, as we can just imagine what Gordon is thinking while looking at that plant, as set up – through visuals and words – in the scan’s very first panel.)

Another writer who had fun with Mayor Dickerson was Ed Brubaker. I’m not talking about the story where Dickerson got tied to the front of a runaway train full of dynamite by the murderous anti-corruption vigilante Nicodemus (a typically uninspired creation from Brubaker’s Batman run). I mean the way Brubaker picked up where Catwoman left off and had the mayor resort to seriously sketchy – when not downright illegal – methods to go after Selina Kyle even when the rest of the world was convinced she was dead.

And sure, there is an obvious illiberal subtext in all these stories. They tapped into a general skepticism about the democratic system, with elected officials for the most part presented as spineless, evil, lying, corrupt, or, at best, short-sighted bureaucrats holding everything back through needless red tape. Then again, that charge cuts both ways, politically. If right-wing populism attacks democracy and left-wing populism attacks capitalism, recent times have made it as clear as ever how thin those dividing lines can be, as immoral businessmen and criminal politicians merge into real-life caricatures that put Gotham’s mayors to shame. Plus, the comics tend to be quite upfront about the fact that the police force is at least as corrupt as the higher-ups…

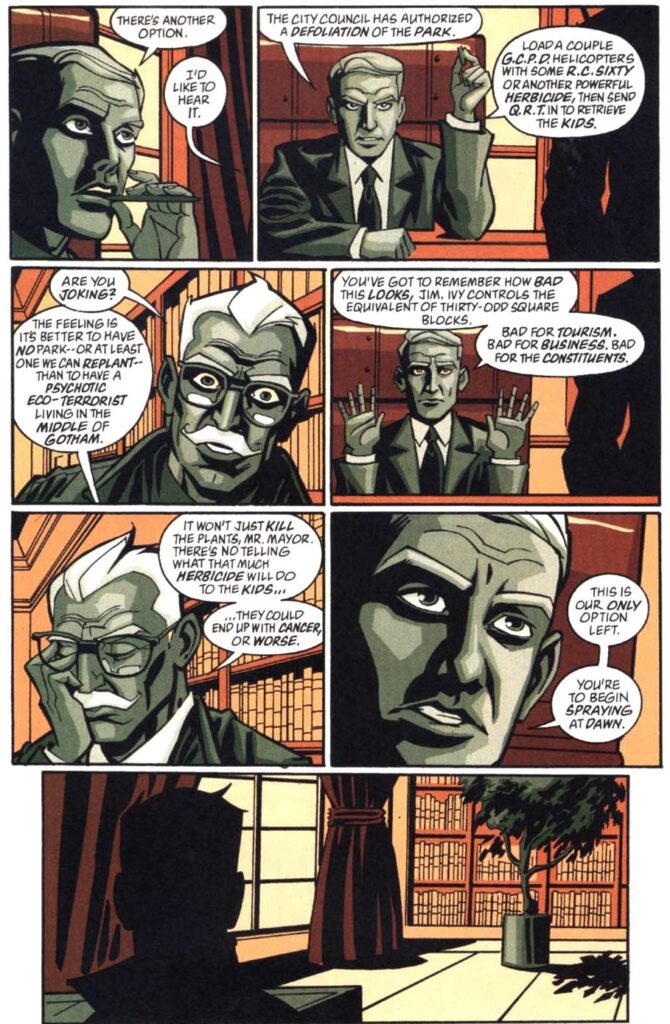

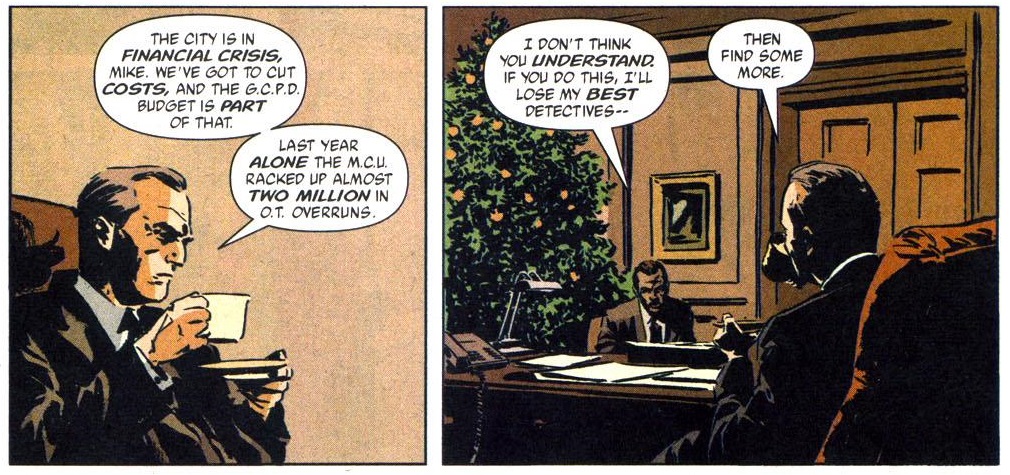

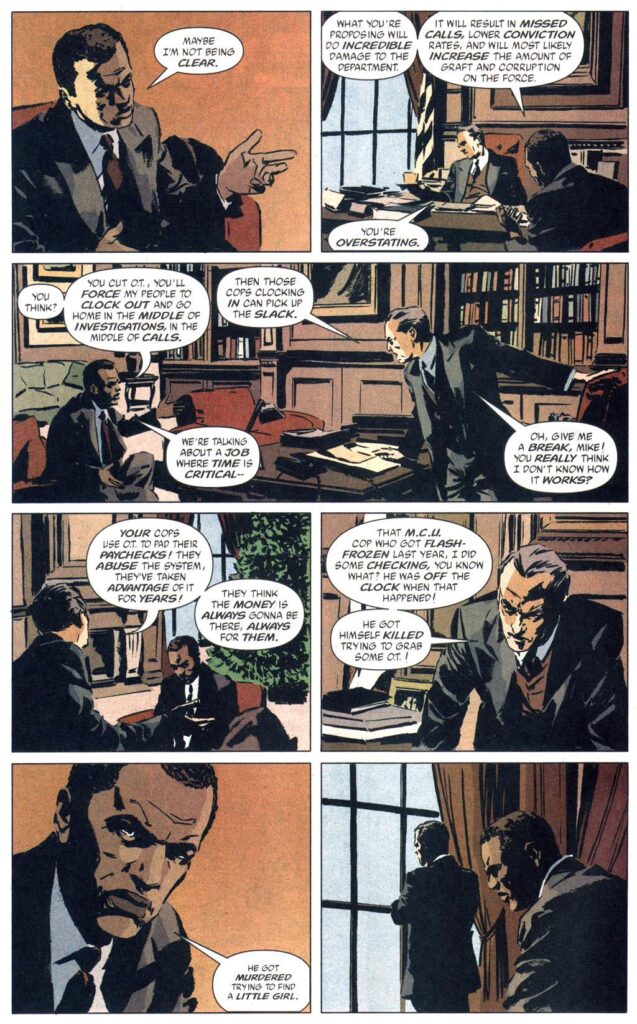

This brings us to Gotham Central (a series where the heroes are mostly honest cops, but they’re treated as the exception rather than the rule in the GCPD), in particular the brilliant arc ‘Soft Targets,’ which features what is perhaps Mayor Dickerson’s most memorable scene. I don’t know if it was Rucka or Brubaker who wrote it (or if they co-wrote it), but it’s a spot-on piece of characterization. It involves the mayor talking to the police commissioner (James Gordon’s successor) about overtime expenses. In a nifty touch, Dickerson wants to defund the police – not for ideological reasons, but because he views everything around him through a corrupt mindset all the time:

Gotham Central #12

If you know Gotham City, you won’t be surprised to find out Mayor Dickerson was soon killed by a psychopath… And you’ll probably be even less shocked to find out that his successor, Mayor Hull, turned out to be in the pocket of a sinister chemical weapons cartel.

At the end of the day, these stories fire in all directions, for entertainment’s sake. Just like even the supposedly woke MCU movies can come across as conservative, so do Batman comics play with both sides of the political field, blending a quasi-nihilistic depiction of official power with a liberal commitment to the system (which compels the Dark Knight to keep sending criminals to the police/courts/prisons even as those continuously prove fallible). Most comics don’t blame the system as much as individual figures who abuse it – like Hamilton Hill or Daniel Dickerson – so the effect is not so much an indictment of a flawed political structure but rather a romanticization of belief in its ideals no matter what (except, you know, for the part where Batman exercises unsanctioned force). The ensuing ideological mess keeps producing interesting moral dilemmas – for the characters and for the readers – embedded in seemingly simple adventures about seemingly well-defined characters.

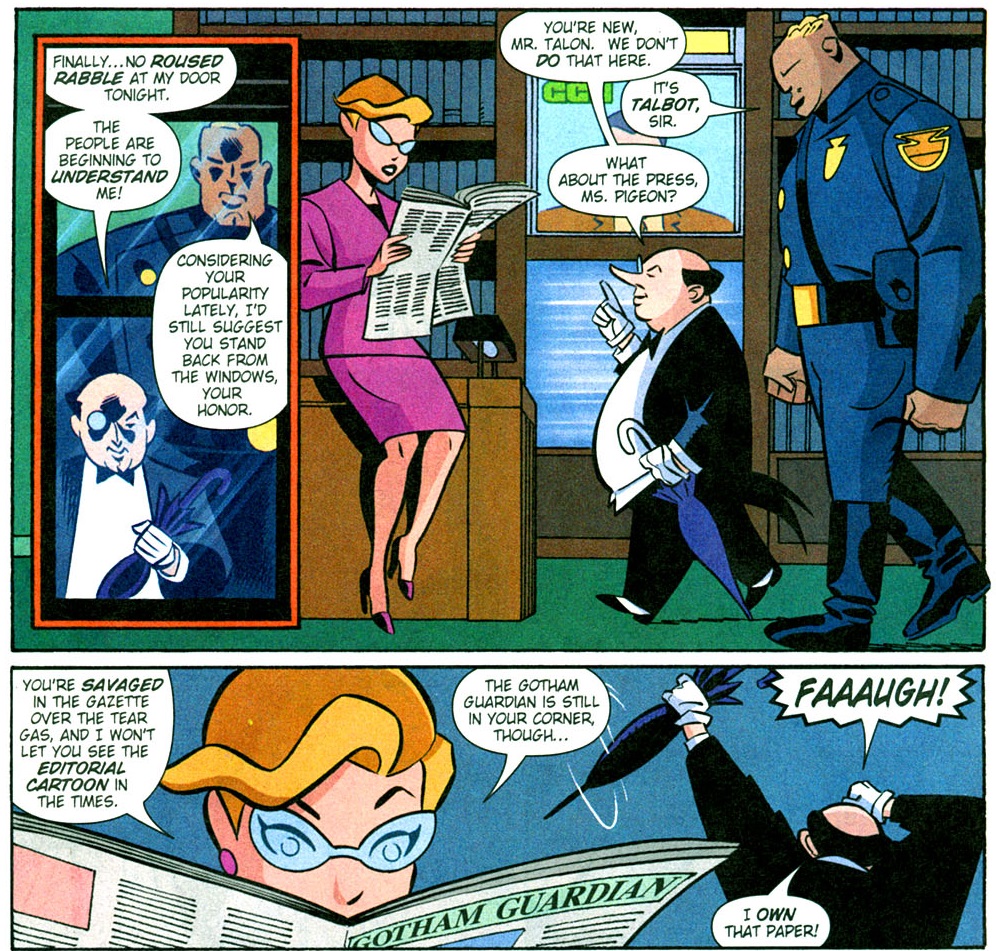

They also sometimes remind you of seemingly simpler times. Take, for instance, the 2003 relaunch of Batman Adventures (one my top 3 favorite runs in this franchise, along with Gotham Central and Alan Grant’s and Norm Breyfogle’s stint on Detective Comics), where Oswald ‘Penguin’ Cobblepot became Gotham’s mayor. Writer Ty Templeton clearly modeled some of the Penguin’s bumbling and authoritarian demeanor on Richard Nixon (especially the resignation speech) and, I suspect, on George W. Bush (engaging in some topical parody at a time when Bush seemed like the lowest you could get). Now that Donald Trump appears poised to be re-elected, however, the Penguin’s chaotic leadership looks quite quaint in comparison with what lies ahead:

Batman Adventures (v2) #13