For a long time, when critics talked about ‘comic book movies,’ they used to just mean silly, exaggerated action films. In the past couple of decades, the term is more likely to refer to a movie that is a direct adaptation of a comic book story or character. In Gotham Calling, I like to explore various connections across these two media, suggesting diverse types of films that should appeal to comic book fans (at least to those who are into genre comics).

Today, I’m adding to that list Richard Lester’s delightful trilogy The Three Musketeers: The Queen’s Diamonds (1973), The Four Musketeers: Milady’s Revenge (1974), and The Return of the Musketeers (1989).

This adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’ classic 1844 novel about four royal swordsmen in 17th century France who undermine Cardinal Richelieu’s plans to expose Queen Anne’s affair with the Duke of Buckingham was apparently conceived, at one point, as a four-hour extravaganza, but director Richard Lester and screenwriter George MacDonald Fraser wisely ended up splitting the project into two installments. As a result, even though The Three Musketeers’ main plot wraps up satisfyingly, that first film finishes with the promise of a sequel, showing us scattered images of what’s to come – like a trailer or, more to the point, a ‘next issue’ blurb at the end of a comic.

Tone-wise, the movies convey some of the full-blown, hell-for-leather excitement of major adventure epics like Richard Fleischer’s The Vikings and Michael Curtiz’s The Sea Hawk, yet they also inject tons of humor into the proceedings. Indeed, between the straight-faced opening of The Three Musketeers and the shockingly grim finale of The Four Musketeers, the bulk of the material feels very much like a sexy comedy interspaced with rollicking action that can match the whimsical thrills of anything on the stands…

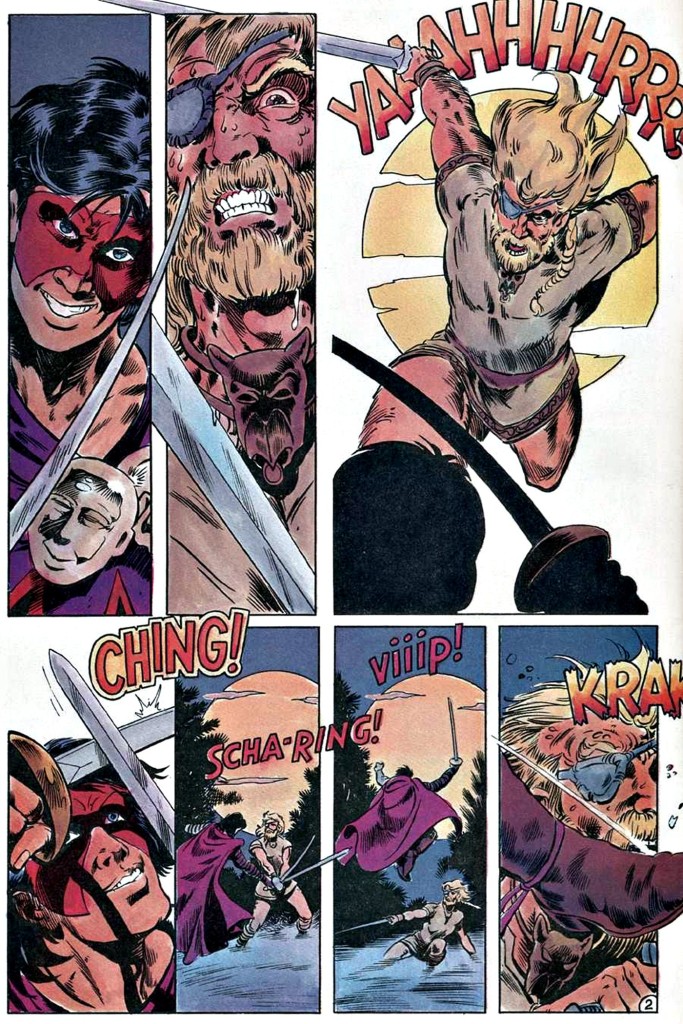

Hotspur #1

Hotspur #1

To be fair, the genre of costumed drama, with its colorful pomposity and ludicrous traditions (by today’s standards), has always lent itself to a kind of joyful slapstick farce. Yet Lester manages to pull off a particularly delicate balancing act, magnificently carried by a cast who is able to comfortably wink at the audience while keeping their dramatic composure, most notably Michael York’s enthusiastic d’Artagnan, Oliver Reed’s pathos-filled Athos, Charlton Heston’s incisive Cardinal Richelieu, Faye Dunaway’s mischievous Milady de Winter, Christopher Lee’s deadpan Count De Rouchefort, and Raquel Welch’s cutely maladroit Constance Bonacieux. (By contrast, Lester’s follow-up historical films verged into one of two directions: Royal Flash is pretty silly while Robin and Marian is surprisingly melancholic).

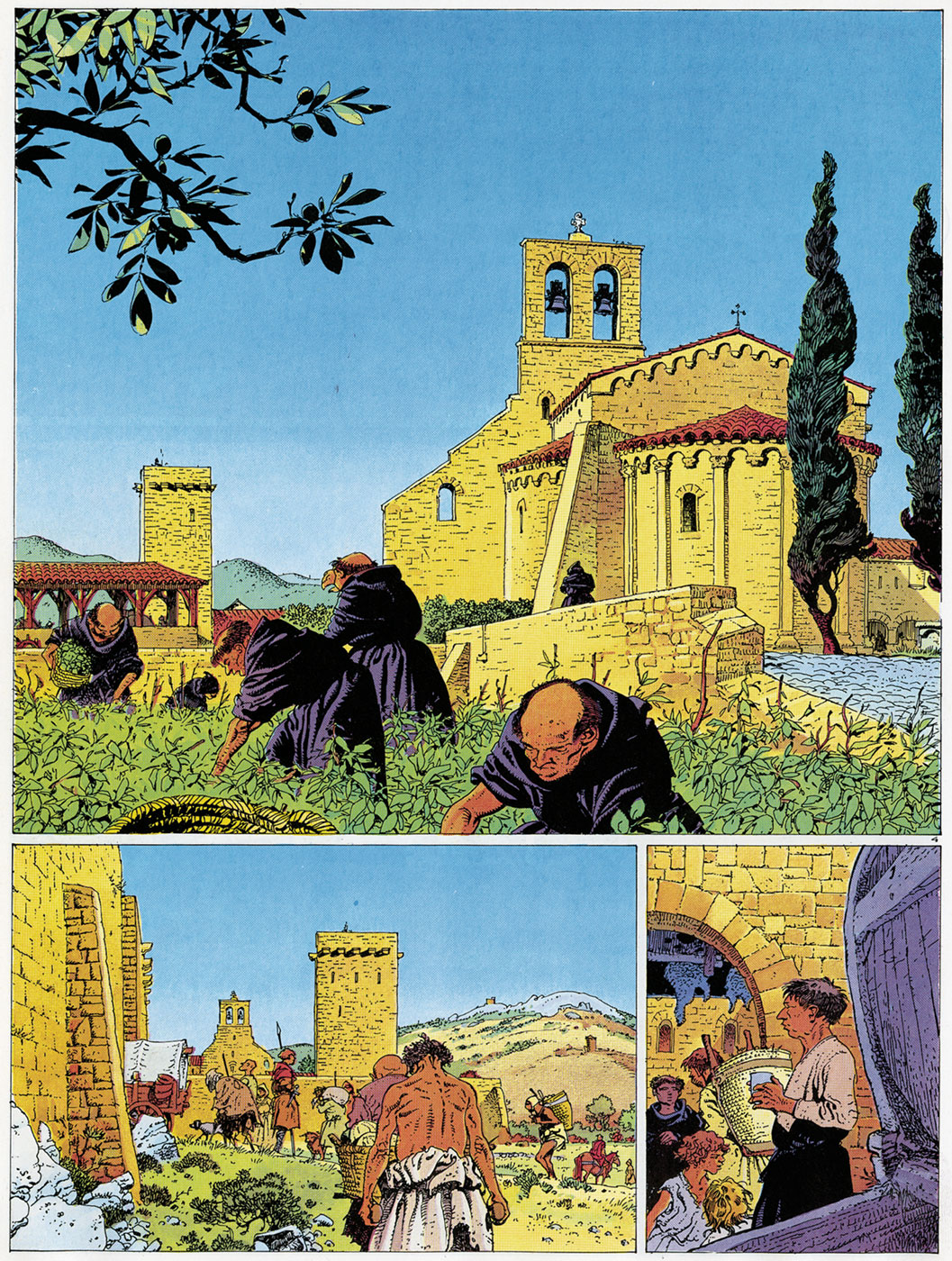

David Watkins’ cinematography and the art direction by Leslie Dilley and Fernando González are a big part of the appeal as well, especially given Lester’s idiosyncratic way of filming adventure – instead of trying to achieve relentless forward momentum, he was not afraid to occasionally slow things down to linger on atmosphere, with plenty of fun establishing sequences about everyday life in post-Renaissance France, zooming in on the settings and extras… It’s the cinematic equivalent of those comic book splash pages or detailed panels where you find yourself appreciating the intricate backgrounds, taking slight detours from the main narrative. Given their dirty, mundane look, they bring to mind Hermann Huppen’s mesmerizingly down-to-earth artwork in his own unsentimental period pieces:

The Towers of Bois-Maury: Germain

The Towers of Bois-Maury: Germain

(Hermann’s talent for crafting devastatingly harsh, realistic landscapes and weather is sometimes used to set up amusing situations, but his sense of irony tends to be more subtle and cruel, closer to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon than to Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers…)

In these sequences, the extras are often heard mumbling amusing asides, which, in a comic, would no doubt be depicted through scattered word balloons:

Starslayer #11

Starslayer #11

I like to think this choice stemmed from a working class sensibility, paying attention to the ‘little people’ and the collective rather than just focusing on the main heroes (like many directors do) by briefly acknowledging the subjectivities of servants living in the periphery of the action. Yet perhaps it was just Richard Lester accepting that aesthetic world-building is one of the main reasons viewers watch period pieces, so he might as well let them take in as much as possible. The result is that we do feel like we are inhabiting each place in this remote era. One of Lester’s trademarks was to show us the games people played for leisure, usually variations of tennis (not just in his swashbucklers, but also in the tense present-day thriller Juggernaut and in the uneven political drama Cuba).

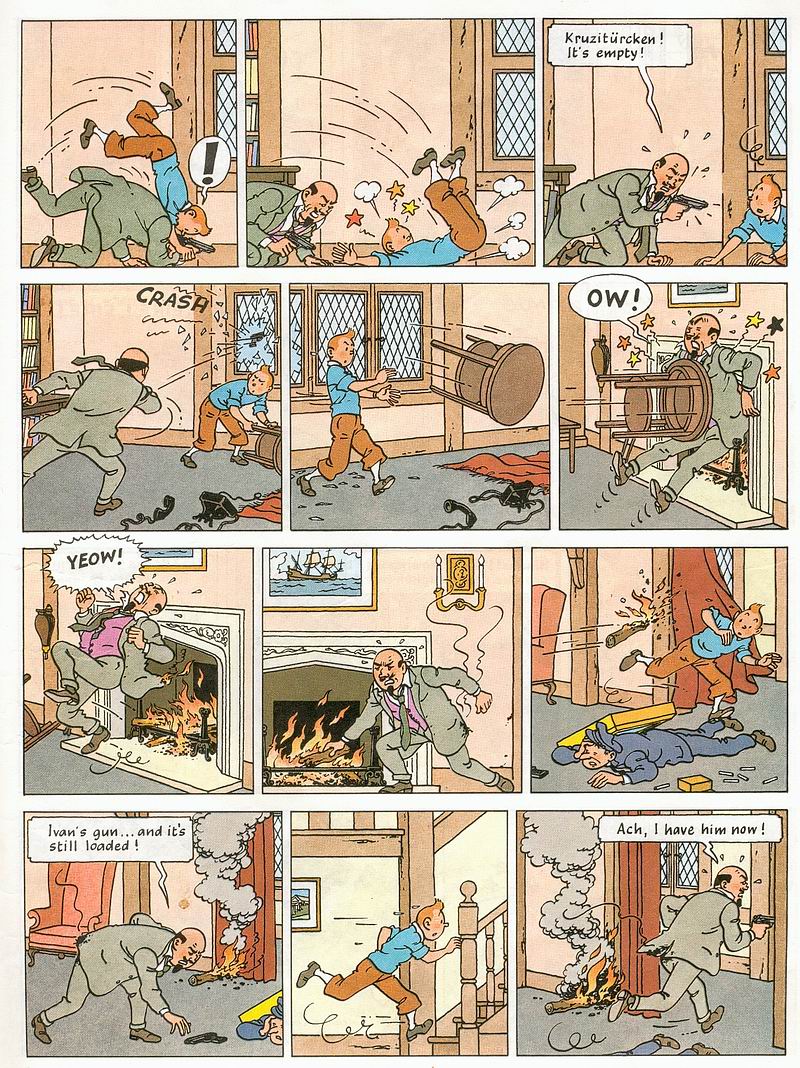

I’m also quite fond of Lester’s approach to materiality, as characters keep bumping into disobedient objects or engaging with elaborate contraptions. Among the barrage of visual gags, there are some truly remarkable action set pieces, including a swordfight in the dark and, in the second film, a large struggle on top of thin ice. Again, this reminds me of comics, in particular the European school of physical comedy of an André Franquin or an Hergé…

Tintin: The Black Island

Tintin: The Black Island

As choreographed by William Hobbs, the fight scenes look entertainingly bumbling and grounded, especially when compared to the athletic, acrobatic elegance of old Hollywood takes on The Three Musketeers, like Fred Niblo’s fun 1921 version (with the great Douglas Fairbanks as d’Artagnan) and George Sidney’s goofy 1948 remake (starring dancer Gene Kelly). The swords feel heavy and the movements of even experienced swordsmen do not always work out as they intend, generating both tension and laughs. All this introduces a gratifyingly revisionist level of realism, not entirely dissimilar to the scene in James Mangold’s Logan where the hero fails to drive through a fence or, to use a well-known example from comics, Bruce Wayne’s awkward early forays into vigilantism in Batman: Year One.

The movies’ revisionism also applies to the story’s values, as the script and direction display an ironic distance towards the fact that the supposed heroes are involved in morally dubious conflicts (like the Catholic suppression of Protestant rebels). Even setting aside the generally nonchalant, stereotypically French attitude towards adultery, in this version the Musketeers are dishonorable scoundrels who steal food and, early on, d’Artagnan basically buys a servant (whom he repeatedly treats like shit). Rather than revise the original’s more outdated views – like Athos’ brutally harsh, judgmental behavior towards Milady de Winter – Richard Lester chose to leave those in and thus let viewers acknowledge by themselves (and perhaps laugh at) the relativity of heroism. By the time we get to The Return of the Musketeers, the approach reaches new levels of cynicism, with our heroes presented as even more inept and morally ambiguous as they go up against a villain (a kickass Kim Cattrall) who accuses them of a deed we know damn well they committed (at the end of the previous film).

As far as revisionism goes, however, we are not talking about the downbeat, grimdark type (if you want that kind, you can find it in Robin and Marian). Instead, these films are closer to a spoof, even if not taken to the absurdist extremes of Blackadder, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, or Love and Death, not to mention the outright parody of Robin Hood: Men in Tights.

Richard Lester’s trilogy doesn’t merely satirize the 1600s’ French and British monarchies (and Oliver Cromwell’s republic, in the last film). These movies also satirize Dumas’ novel and the multiple iterations of this material – and the wider swashbuckler genre – which have whitewashed or even glorified its values.

The metafictional dimension, acknowledging the tradition of adaptations that came before, can be seen, for example, in The Return of the Musketeers’ cameo by a buffoonish Cyrano de Bergerac – part of the joke is that Cyrano is played by Jean-Pierre Cassel, who had played King Louis XIII in the previous movies and, more importantly, had played d’Artagnan himself in 1964’s Cyrano et d’Artagnan (where Cyrano was played by José Ferrer, reprising his role from 1950’s – very witty – Cyrano de Bergerac). And yes, this Easter Egg is the type of intertextual deep cut you often find in mainstream superhero comics.