While ultimately no comic could top Shubeik Lubeik as Gotham Calling’s book of the year, there were strong contenders I left out but which I think deserve highlighting anyway… Now, I haven’t been reading as much as I used to, so I’m sure I missed some cool works throughout the year, but there were still plenty of times when I found myself reinvigorated in my passion for this medium.

With that in mind, here are half a dozen comics from my 2023 shortlist, in alphabetical order:

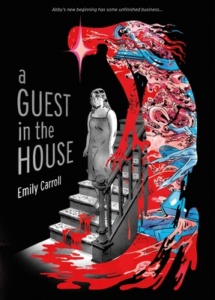

A psychodrama that escalates into full-blown horror, this terrific graphic novel delves into the anxieties of Abby, a young woman living in a creepy house by the lake with her older husband, his teenage daughter, and the looming, phantasmagorical presence of his dead wife. The main strength of A Guest in the House is the way it gets us inside Abby’s head – like Shubeik Lubeik and a couple of other books on this list, this work takes great advantage of comics’ ability to let us visualize mental states. Along with a sensitive and unsettlingly ambiguous script, Emily Carroll’s powerful drawings thoughtfully render Abby’s haunted relationship with the people and elements around her, not least by occasionally tinging the black & white artwork with dreamy touches of red and other colors, expanding the technique used in the later volumes of Miller’s Sin City and, to an even greater effect, in Strömquist’s Fruit of Knowledge (notably in the chapter on menstruation).

The premise, of course, riffs on Rebecca, What Lies Beneath, and countless other yarns about insecure wives questioning their sanity while suspecting something is afoul (there is even a turning point in which the protagonist gets a radical haircut, like in Rosemary’s Baby), but Carroll is an intelligent writer who uses familiar tropes to play with readers’ expectations, leaving us unsure about what is real and what is imagined until the shocking ending.

In 16th-century England, amongst the tumultuous antipapist reform, a young green-haired girl and the Moorish scribe who chronicles her adventures set out on a swashbuckling quest to fight the Devil. As entertaining as it is intriguing, this is one of those original comics where I was never entirely sure what to expect: on the one hand, much of Gospel reads like a carefully crafted period piece; on the other, even setting aside the supernatural elements, the book is peppered with anachronistic touches, from a character using air quotes to the local population’s general acceptance of the unconventional heroes.

The apparent inconsistencies are eventually explained, as Will Morris confidently weaves multiple layers into the narrative, resulting in a Gaiman-esque ode to storytelling itself (from the Bible to history books, from fairy tales to self-delusion). That said, what enables Morris to pull off such a balancing act is his sharply clean – and engagingly bouncy – artwork. Like most items below, this is one of those books that I’ll certainly revisit in the future, picking it up off the shelf and flipping through the pages for the sake of pure visual delight.

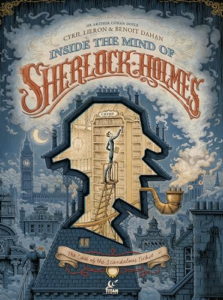

If there was a second place on my top 2023 comics, it would definitely go to the English translation of Inside the Mind of Sherlock Holmes. It’s not just that this is a wonderful Sherlock Holmes mystery, although it surely is that as well, what with the sprawling chain of clever deductions, the droll characterization (perfectly in sync with the couple of Arthur Conan Doyle novels I’ve read), the Victorian steampunk aesthetics, the tragic villain with an eccentric plan, and the elaborate story informed by the time period (most notably the infamous Opium Wars) leading up to a viciously ironic ending.

What makes this book shine is that Cyril Lieron and Benoit Dahan show us Holmes’ thought process throughout the case, whether by peeking inside his head (which looks like a house full of archives and props where the detective gets to literally rearrange his memories and ideas) or by having a thread connect the various clues and locations. By brilliantly illustrating the act of reasoning and processing information rather than confining it to verbal exposition (like in the original texts and in most audiovisual adaptations), we get a work that feels constantly dynamic and visually mesmerizing beyond the occasional action set pieces (even if those are also pretty incredible). Moreover, besides the superbly designed layouts, we get all sorts of extra touches appealing to readers’ playful side: looking at some pages through light reveals hidden details, curbing or folding other pages changes their meaning… In other words, more than a great Sherlock Holmes comic, this is a book that really makes the most out of the medium’s potential.

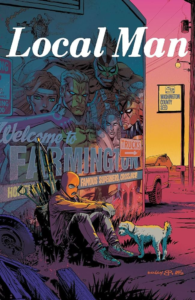

The latest take on the subgenre of smart, R-rated superhero comics follows Crossjack, a disgraced hero forced to move back to the small town he came from, where he’s forbidden from fighting crime (under a copyright infringement law), which becomes a particularly tricky issue once he gets falsely accused of murder… The meta twist is that Crossjack used to belong to the type of outrageously *extreme* super-team you could find on the pages of 1990s’ Image Comics, retroactively fitting him into that shared universe.

Ten years ago, Tim Seeley had already written one of the niftiest reboots of early Image properties, the underrated Bloodstrike, but that one slickly updated the original concepts and sensibility while Local Man – co-created with Tony Fleecs – is more about exploring the publisher’s evolution. The main story (with art by Fleecs, moodily colored by Brad Simpson) is told in a decompressed, relatively understated tone, not unlike That Texas Blood, in sharp contrast to the back-up flashbacks (drawn by Seeley with deliberately garish colors by Felipe Sobreiro) rendered in the bombastic, trying-hard-to-be-awesome style of Rob Liefeld, Jim Lee, or J. Scott Campbell, complete with over-the-top cheesecake and exposition-heavy dialogue. Thus, the series applies to 90s’ comics the same sort of amusing pastiche-and-contrast approach that those comics (most notably Alan Moore’s Supreme) used to apply to the Golden and Silver Ages… And sure, the actual plot isn’t particularly inventive, but I can’t resist the way Local Man works both as a love letter to the silly source material (many of the heroes’ preposterous designs are based on the creators’ own pre-professional work, going back to their teens) and as a meditation about embracing maturity.

(The first volume, Heartland, doesn’t yet collect the special Local Man: Gold, which came out in the meantime and pushes the tribute to Image’s history even further by crossing over titles as disparate as Cyberforce, Street Angel, Battle Pope, and Love Everlasting, among many others!)

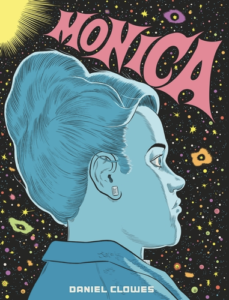

Daniel Clowes’ latest genre-bending tour-de-forceis one of those graphic novels that invites multiple reads… and multiple readings. Superficially, it looks like an indie anthology of interconnected stories, many of which seem inspired by old comic-book traditions, such as war, romance, horror, and crime tales. While admittedly riffing on EC’s artists, though, Monica is not a full-on pastiche, as the cast brazenly sound like Clowes’ typical alienated, sardonic characters (‘you’re not really special, just the unwanted fetus of two random fuck-ups caught in a confusing historical moment’). On a more direct level, the narrative tapestry adds up to the life story of the titular daughter of a free-wheeling hippie, who grows up to be, at different points, a successful business woman and a member of a creepy, decrepit New Age cult. Monica tries to piece together what happened to her long-gone mother and the identity of her father, but this obsession with her biological roots is ultimately part of a wider reconstruction of some of the darkest corners and legacies of America’s flower power era. Then again, the chapters slightly contradict each other (and the tone veers jarringly from ultra-realism to utter fantasy), so you may wish to reinterpret some of them as hallucinations, as stories-within-the-story written my Monica or by the ersatz-Clowes who shows up later on, or merely as the product of unreliable memory/information/narration.

If this sounds too meta and formalist, it is to Clowes’ credit that he still manages achieve a compelling, emotionally resonant sense of isolation and personal anguish amidst his signature blend of heartbreaking moments and pitch-black laughs.

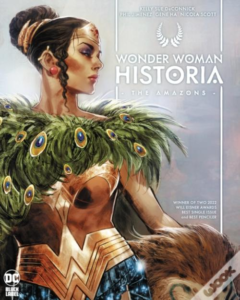

DC’s Black Label has been putting out some of the coolest comics out there, in terms of both original concepts (my gushing praise for The Nice House on the Lake here) and neat takes on existing properties (Jock put the larger format and his street art-infused style to very good use in One Dark Knight, which reaches the intensity of an episode from the first season of The Bear). Still, Wonder Woman Historia: The Amazons didn’t exactly seem aimed at me… It’s yet another origin story of a major character (I’ve grown quite sick of those) done as a portentous epic geared more towards mapping a vast mythology than towards properly developing each cast member. Despite the misleading cover, the book isn’t about Wonder Woman, but about the creation of the Themyscira community in which she was raised (the backmatter indicates the project’s inspiration came from the initial minutes of 2017’s Wonder Woman movie) – and I would’ve been very happy to read a fun sword & sorcery adventure starring the Amazons fighting gods, but this is essentially the first act of a larger saga. Hell, it feels like the foreword!

Oh well, the same can be said for Batman: Year One, so I suppose you can get away with it as long as the book has a talented creative team at the top of their game. I’m glad to say that’s case here. I usually enjoy Kelly Sue DeConnick’s work and, sure enough, her punchy narration – beautifully rendered by the magnificent letterer Clayton Cowles – did a lot to win me over, even if the best bits were when she stopped setting things up and just approached all these pantheons and legends as a playground in which to unleash crazy action. Deconnick does a particularly fine job of writing to each artist’s strengths, letting Phil Jiminez introduce this cosmic opera through maximalist, packed-to-the-brim pages in which every single millimeter and design choice seem to have been the result of lengthy research and serious consideration. She gives Gene Ha a relatively more grounded chapter, more focused on Hippolita and a couple of other key figures, with greater emphasis on human drama, close interactions, and facial acting. Suitably, Nicola Scott then gets to put her ethereal pencils in the service of a glorious climax where the clash of realms lends itself to the sort of iconic images that could fit in a classical art museum.

That said, the colorists are the real stars here. Jiminez’s hyper-detailed compositions are elevated to even more intense vibrancy by the trio of Hi-Fi, Arif Prianto, and Romulo Fajardo Jr, whose hues help sustain the book’s balance between storytelling and pageantry. In turn, Wesley Wong imbues even the most ‘mundane’ panels with a mystical, nocturnal atmosphere, while Annette Kwok brings out the painterly quality of Scott’s ink-washed drawings. The result is nothing short of breathtaking.