A while ago, I did a post about violent superhero movies that explore how scary it would be if there were actual super-beings around, especially ones less bound by old-fashioned morals than your regular mainstream heroes… This line of speculation has a long tradition in comics, from the brutal classic Miracleman #15 to the unsettling graphic novel A god Somewhere, not to mention the entertaining Superman-gone-bad series Irredeemable. It’s not just the odd comic, either: there are entire shared superhero universes – like WildStorm and Valiant – where morality is practically a secondary thing, as most protagonists will nonchalantly slaughter anyone who gets in the way and many are part of shady teams run by ultra-cynical bastards.

The greatest example in recent times is, by far, Joshua Dysart’s epic, Imperium.

Imperium is the culmination of a certain subgenre of morally ambiguous superhero fiction whose lineage goes back to the 1980s’ deconstructionist movement (spearheaded by Alan Moore) and the 1990s’ Image explosion (where nihilism was part of the whole edgy, ‘extreme’ attitude), but which reached a peak in the early 2000s, most notably with WildStorm’s revolutionary ‘widescreen blockbuster’ extravaganza The Authority. Following that comic’s lead, the rest of WildStorm’s output sought fresh and thought-provoking ways of reimagining the superhero genre, resulting in some of the most experimental works in the field, both as part of The Authority’s universe (Planetary, The Intimates, Wildcats version 3.0, Sleeper, The Establishment…) and beyond it (The Winter Men, Ex Machina, and Automatic Kafka, among others).

Overall, the emphasis was really more on the ‘super’ part of ‘superhero,’ with the main appeal being the catharsis of watching incredible powers unleashed in inventive ways, as well as of thinking through the widespread sociopolitical implications that could come out of such supernatural phenomena (thus breaking long-established taboos in the genre). What made WildStorm so special was also the audacity of engaging with long-term global transformation at the level of an expanded universe with dozens of series, upstaging the short-lived ‘events’ of DC’s and Marvel’s core continuities.

After that version of the WildStorm Universe was brought to a close (in part collapsing under the weight of all the massive destruction it had accumulated), its spirit of cleverly blending the excitement of superhero fantasy with more mature sensibilities was kept alive in 2012’s reboot of the Valiant Universe. Many of the books to come out of that reboot presented super-powers in a terrifying way, avoiding the genre’s more simplistic morality plays. For instance, despite the title, in the early stages of Matt Kindt’s Unity – one of Valiant’s core team books – there was hardly an issue in which one of the stars of the series wasn’t trying (or plotting) to kill at least one other major property (they finally settled into a more cohesive group later on, with the ‘Homefront’ story-arc doing a particularly neat job of conveying their increasing sense of belonging to a team).

Among Valiant’s catalogue, however, I would say that 2015’s limited series Imperium – including the 2019 sequel The Life and Death of Toyo Harada, which was basically the second part of the story – manages to stand out as the most sophisticated corollary to The Authority’s push to move superheroes into a more politically conscious, morally uncertain mold of storytelling while at the same time preserving (or even escalating) the spectacle that defines the genre.

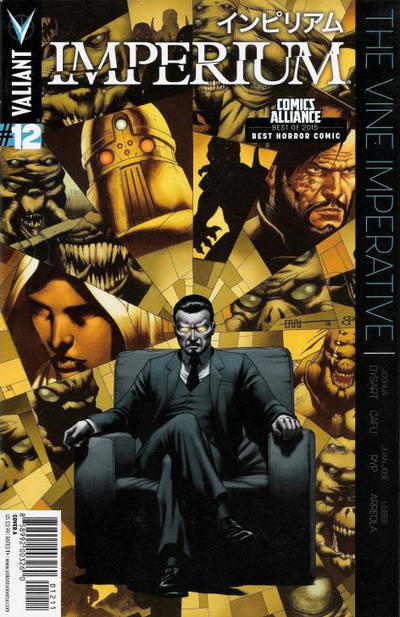

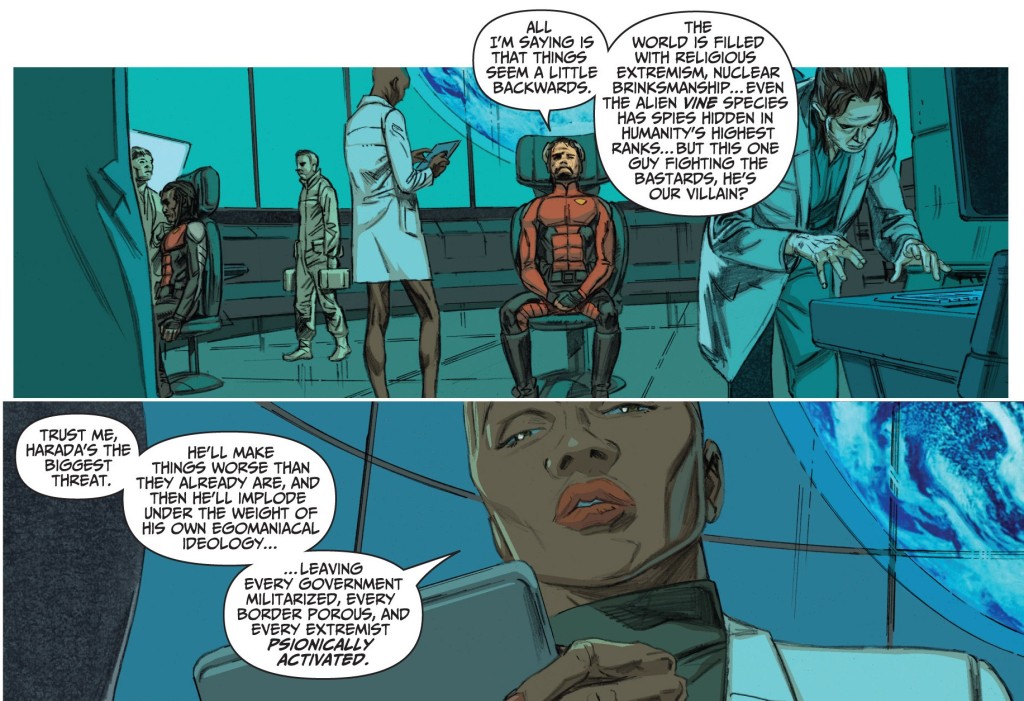

Imperium #2

Imperium #2

The series’ premise is that, after his decades-long cover as a philanthropic businessman is compromised, Toyo Harada, the most powerful super-being (aka ‘psiot’) in the Valiant Universe, decides to bend the world’s will by force in order to usher in his vision of post-scarcity utopia. For that, he gathers a host of followers with psionic abilities and declares an all-out war on all sorts of fronts, from messy African politics to the shadowy world of military contractors like the sinister Rising Spirit corporation. Along the way, we get a maximalist barrage of mind-blowing sci-fi concepts, hyperbolic dialogue, and sheer carnage.

You’ll find no decompressed storytelling here: each issue is filled to the brim, as Imperium relentlessly pits telepathy against telekinesis, out-of-this-world brilliance against ruthless cunning, and futuristic technology against unbelievable brute force. The conflict keeps moving and escalating, as double-crosses pile up and key characters are removed from the picture. It makes sense to think of Imperium as a smart superhero version of Game of Thrones – for one thing, Joshua Dysart (one of the most interesting writers working in the medium at the moment) makes sure there are always a few redeeming motivations and likable (or at least charismatic) characters on each side, so that your allegiances are likely to shift as we change perspective, even within a single issue. If there is such a thing as ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys,’ they are all over the place – rather than root for them, you just sit back and dread as you watch them destroy each other.

Indeed, as with those WildStorm comics from the turn-of-the-millennium, a big part of Imperium’s appeal is to watch large-scale exhibitions of devastating power, be they in the form of over-the-top industrial espionage, international politics, psychological mind games, cyber-warfare, or time-manipulation… It’s all robustly rendered by Valiant’s regular artists: Doug Braithwaite, Scot Eaton, CAFU, Juan José Ryp, and Khari Evans. As for Brian Reber’s and Ulises Arreola’s dreamy, blinding colors and Dave Sharpe’s versatile lettering, not only do they secure the series’ visual coherence, but they also enhance its bombastic vibe.

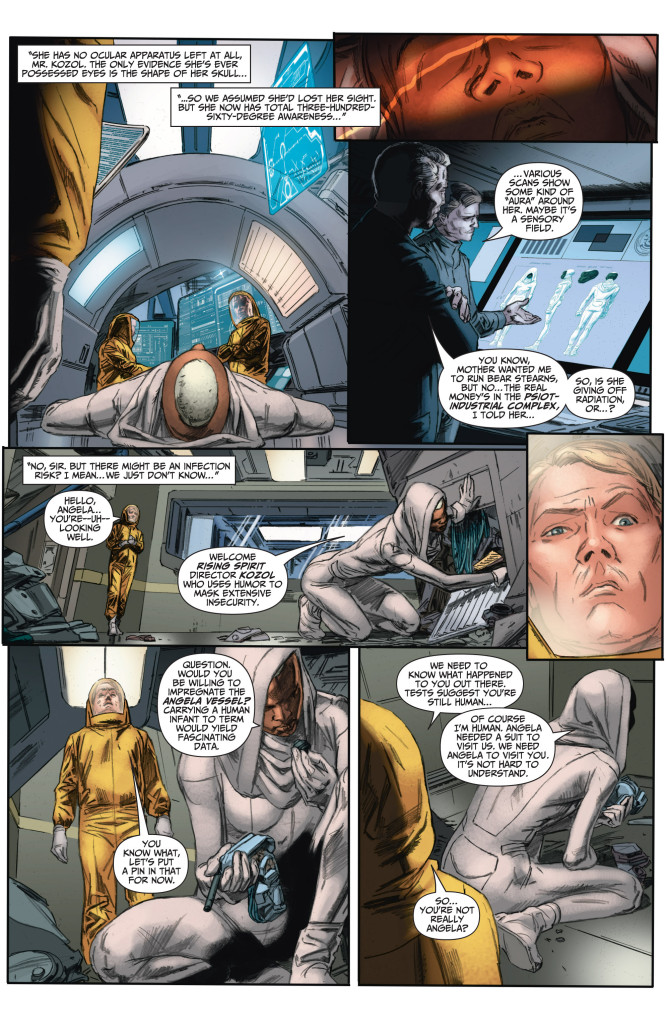

The dialogue is in tune with the comic’s go-for-broke tone. At one point, when a character is about to shoot another, he yells: ‘Time for some high-velocity, transcortical lead therapy!’ Even better: during a particularly thrilling submarine heist (in which Toyo Harada tries to steal a psiot’s brain), the director of Rising Spirit utters these immortal lines to the crew: ‘Every single one of us has to be willing to die to keep that brain in our possession!! The world and the stock value of our company is at stake here, people!’

Joshua Dysart wastes no words, with every line seemingly designed to convey as much information, characterization, and exhilaration as possible. Taking a page from the Warren Ellis/Jonathan Hickman playbook, there is barely a balloon or caption that doesn’t elicit some kind of amazement or amusement in the readers…

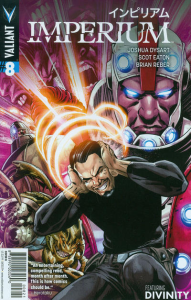

Imperium #4

Imperium #4

Perhaps I make it sound shallower than it is. Toyo Harada is presented as an authoritarian, megalomaniac superhero/villain, but also as a tragic figure who is resorting to extreme methods in a laudable fight against global injustice and poverty (gathering support from India, Brazil, Indonesia, Iraq, Ukraine, Mexico, Kiribati, Cuba, and the Democratic Republic of Congo along the way). Questioning whether ends can ever justify the means, Imperium shows us both the benefits and the sacrifices inherent to Harada’s proto-socialist crusade, as well as a host of unintended consequences, with the series repeatedly commenting on the link between conflict and economics.

Moreover, like all the best fantasy and science fiction, not only does Imperium conjure up imaginative scenarios, but it then gets a lot of dramatic mileage out of the complicated feelings they would generate. It can be truly absorbing just to watch characters engage with utterly original situations and, in the process, develop original emotions. Just like in the brilliant TV show Counterpart you get a whole range of reactions to the existence of doppelgängers (starting from scientific curiosity, identity crisis, theological interrogation, anthropological distrust, political pragmatism, and existentialist revelation – and then building up from there in increasingly nuanced and personal ways), in Imperium there is a remarkable plurality of ways in which people – and aliens and forms of artificial intelligence – relate to the (super)power struggle taking place around them.

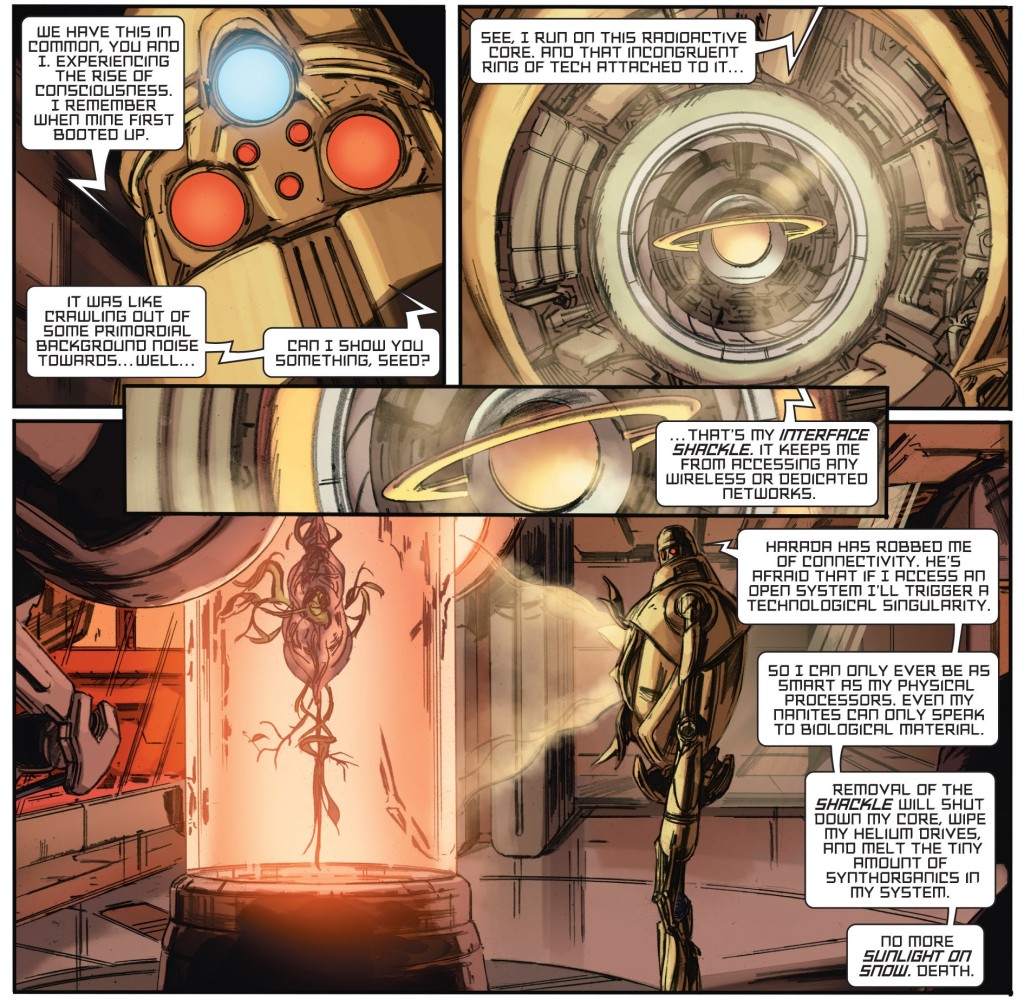

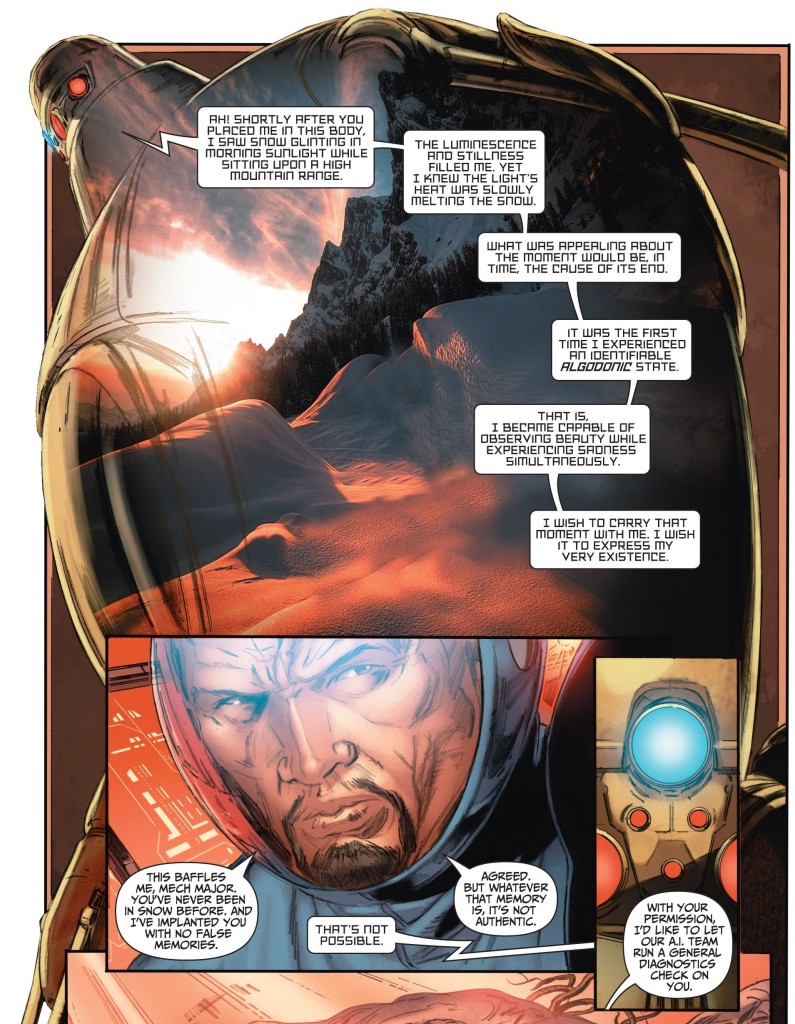

In fact, amidst all the kickass action and geopolitics, the series actually has plenty of moments of tenderness and comedy, usually involving Harada’s medical robot Mech Major, whose A.I. has developed consciousness and insists on being called ‘Sunlight on Snow.’ My favorite scene involves Sunlight on Snow talking to a plant (later revealed to be the seed of a sadistic alien monster):

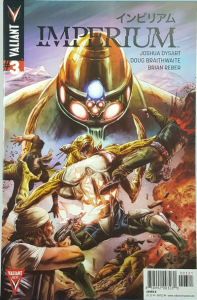

Imperium #3

Imperium #3

Besides setting up a later plot point, the scene manages to be both melancholic and funny. The fact that Doug Braithwaite, Brian Reber, Ulises Arreola, and Dave Sharpe play it completely straight lends even more humor to the abrupt contrast between the sensitive robot and the cold-hearted, logical human. (The tension between Toyo Harada’s humanitarian ideals and his ultra-pragmatic mind is, of course, a key running motif in the whole series.)

Indeed, a major reason for Imperium’s creative success has to do with the fact that Dysart’s scripts are so sharply illustrated. Even when dealing with the most inconceivable creatures and powers, the artwork remains somewhat naturalistic, albeit not meticulously detailed (except for the bits by Juan José Ryp, whose style comes the closest to the Chris Weston/Geoff Darrow school of drawing). For all the sci-fi elements, the comic is certainly set in a recognizable version of our world, with Khari Evans actually working several photographic samples into his backgrounds.

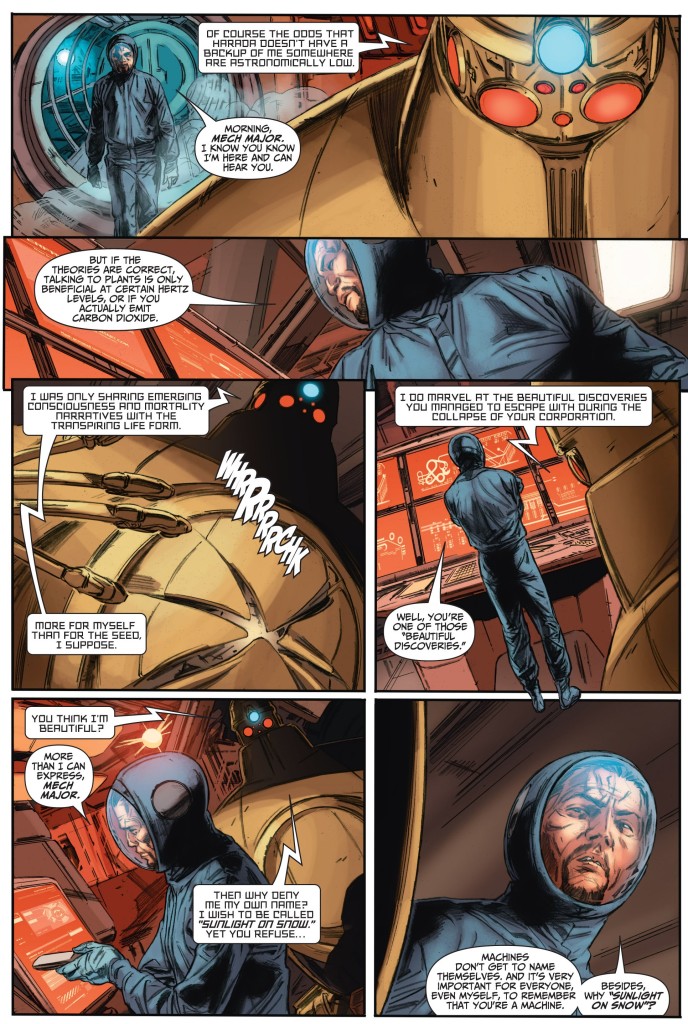

The artists switch dynamically from ‘talking head’ close-ups to splashes and heady sequences, including a dazzling flashback about an exploration mission to a higher dimension (again, by Braithwaite), a cosmic clash between Harada and a godlike Soviet cosmonaut (by Scot Eaton), and a memorable scene inside Albert Einstein’s dying mind (by guest-artist Adam Pollina). The ensuing look cements the idea that, as far as superhero comics go, we couldn’t be farther from Kirbyesque bluntness – instead of stylized blocky figures and stark colors histrionically expressing clear, melodramatic conflicts, every element of Imperium speaks to a slipperier and more elaborate worldview.

See how CAFU – here working with colorist Andrew Dalhouse – practically depicts this siege as a color-coded infographic:

The Life and Death of Toyo Harada #1

The Life and Death of Toyo Harada #1

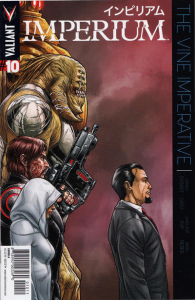

As if all this wasn’t enough, Imperium’s fourth arc prominently features Livewire, one of my favorite characters in the Valiant Universe. Much like The Authority’s Engineer, Livewire is a psiot who can control machines with her mind, which means that we keep getting quasi-poetic slices of technobabble like this one:

Imperium #15

Imperium #15

Valiant fans, in particular, are bound to have a field day with Imperium and The Life and Death of Toyo Harada, since they tie into various corners of the company’s shared universe, including a major plotline about the alien Vine (from X-O Manowar) and even a nifty sort of crossover with the first Divinity mini-series. That said, these comics aren’t hard to follow on their own, even if you’ll get much more out of them if you’ve at least flipped through the pages of Dysart’s earlier runs on Harbinger and Bloodshot.