Lately I’ve been writing mostly about sci-fi for this section of the blog, so I think it’s time to shift our attention to another great adventure genre: fantasy. Fantasy is one of those umbrella genres that covers a massive spectrum of stories, from kid-friendly escapades to highbrow magic realism. Since it can essentially be applied to all sorts of narratives where the physically impossible occurs, fantasy also easily lends itself to expansion and hybridization with other genres, especially with those that revolve around generous leaps of imagination, like supernatural horror and science fiction set in the far-off future or other planets.

One of my favorite types involves fantasy’s crossbreeding with two-fisted adventure, creating counterintuitive settings and rules and then unleashing chaos upon them. If you share my passion, here are some comics for you:

SAVAGE TALES

(the original series)

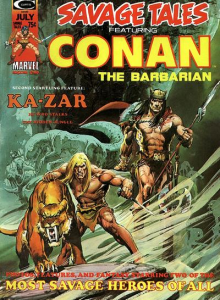

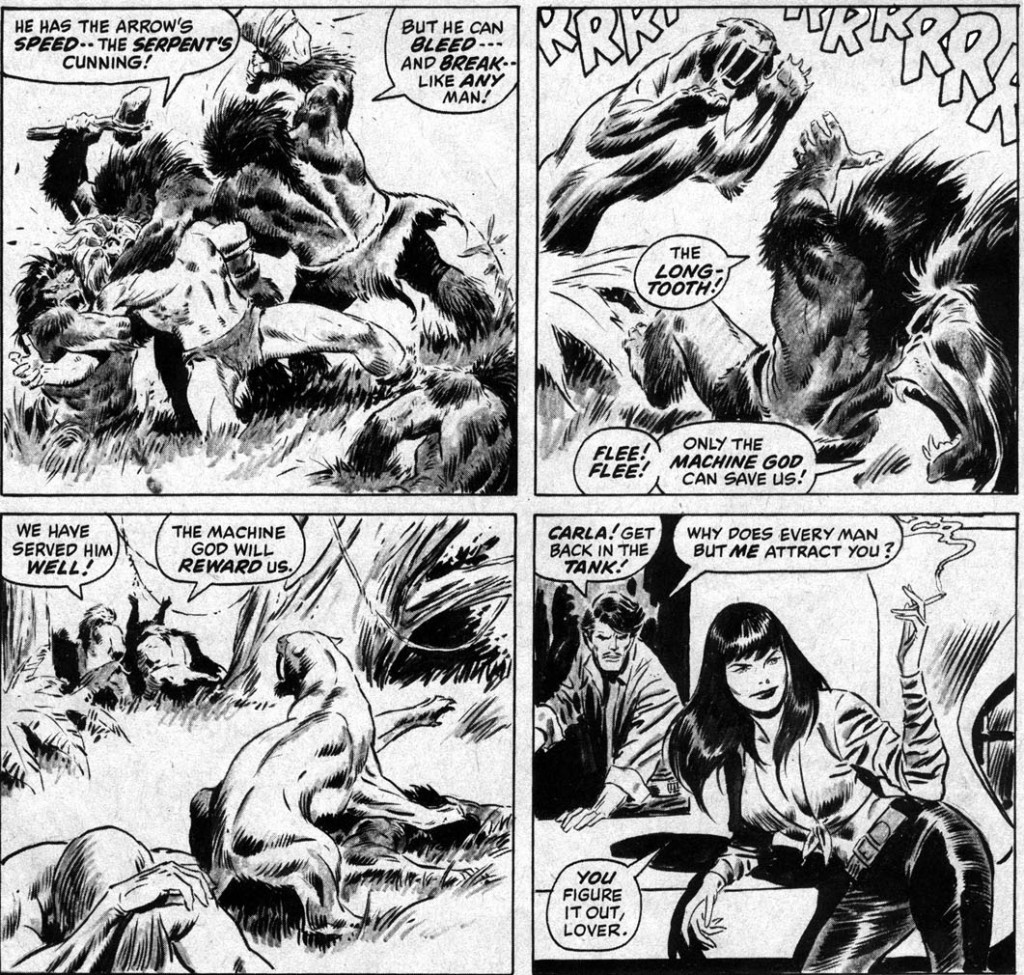

Savage Tales #4

Savage Tales #4

Savage Tales was originally an anthology published by Marvel in the ‘70s packed with over-the-top violence involving monstrous creatures, voluptuous women, and scantily-clad, ultra-muscled anti-heroes. Published in black & white, with more adult-oriented material (i.e. gore and nudity) than Marvel’s regular titles, it was part of the company’s effort to circumvent censorship by putting out magazines whose format was technically not covered by the Comics Code Authority (following the lead of Warren’s horror mags Eerie and Creepy). The first issue came out in May 1971, but clearly the publisher wasn’t yet ready to commit to something this bold – it took a hiatus of over two years (including a change in management and a sword & sorcery boom) before Savage Tales resumed publication, with the second issue coming out in October 1973 and then carrying on with a bimonthly schedule until July 1975. The eleven issues that did come out, though, are a great entry point into the fantasy subgenre I mentioned. Directly inspired by the writings of Robert E. Howard, in this comic you’ll find the pure version of all the classic tropes (the ones Terry Pratchett later spoofed in Sourcery, here played dead straight).

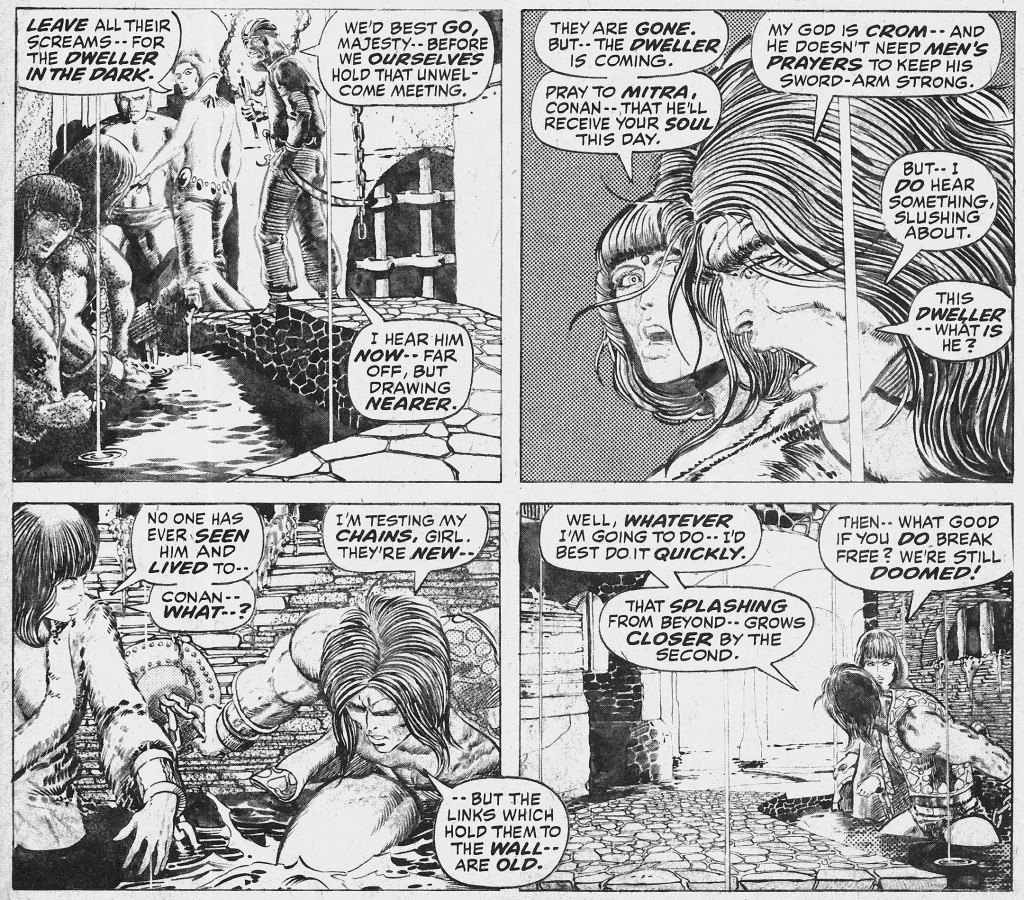

The most acclaimed strip of the series, Roy Thomas’ Conan the Barbarian, is pretty much my platonic ideal of what a sword & sorcery comic looks like. These adaptations of Howard’s ‘The Frost Giant’s Daughter,’ ‘Red Nails,’ and ‘The Dark Man’ – plus a couple of original tales – follow the famous warrior of the Hyborian Age (a fictional era before the beginning of recorded ancient history) as he slaughters giants, saves a gorgeous woman from ritual sacrifice, battles a powerful wizard, and temporarily becomes the sex slave of a capricious queen. Conjuring the feel of half-remembered legends, complete with puzzling mythologies and uncomfortably distant moral standards (especially when it comes to sexual politics), these vicious yarns do not shy away from the notion that Conan is a cunning, instinct-driven pile of condensed testosterone. Besides the protagonist’s panther-like characterization (to use the narrator’s favorite description), a big part of the appeal is the setting itself – not just Barry Windsor-Smith’s, Gil Kane’s, and Jim Starlin’s staggering renditions of the majestic Nordic landscapes, detailed garments, and faux-period architecture, but also the nonchalant way Thomas’ poetic narration and dialogue bring up odd tribes and religions without properly introducing them to readers (which, ironically, makes us feel more complicit with this world, as if it’s a given that we share these references).

Also worthy of note, there were a few cool stories starring the similar Brak the Barbarian, including one scripted by the hero’s original creator, John Jakes, and a two-parter adapted by Doug Moench, whose own flair for purple prose made him an easy fit for the material (‘The night fills with the remote beat of timbrels, the distant clap of hands, the muted shriek of laughing… and the close slap of small feet stamping fog-smothered cobbles… And Brak stands in the midst of it all, cursing the perversity of a city which forces a man to battle children…’).

The other main feature was Ka-Zar, about the Tarzan-like exploits of the titular jungle lord – and his faithful sabretooth tiger – in the Savage Land (Marvel’s hidden territory where dinosaurs still roam). Although not as smart as Mark Waid’s work with the character in the late ‘90s, there was an appealing rawness to the Ka-Zar strip. Scripted by Stan Lee and Gerry Conway, these were unabashed pulp comics where the exaggerated luridness was part of the fun. The key attraction, though, was John Buscema’s – and later Steve Gan’s – stylish art, especially their ability to pull off pulse-pounding action scenes:

Savage Tales #1

Savage Tales #1

For the most part, Savage Tales had an old-school epic adventure vibe, with the kind of outdated exoticism and earnestness that you could also find in some movies of the previous years (Duccio Tessari’s Secret of the Sphinx or Robert Day’s She), in contrast to the tongue-in-cheek attitude of the later Indiana Jones franchise…

Besides the running strips, the magazine had text pieces, loose short stories, and ‘pilots’ for new concepts. Most notably, the horror character Man-Thing made his debut here before getting his own fascinating series. In turn, Black Brother, a riff on blaxploitation penned by Denny O’Neil (under a pseudonym) – about a badass African politician fighting against neocolonialism! – was never heard from again. Among the short stories, highlights include Len Wein’s and Steve Gan’s amusing ‘Dragonseed’ (starring the aptly named Marok the Merciless), Archie Goodwin’s and Russ Heath’s harsh ‘Intruder!’ (about a Vietnam veteran who stumbles into the Savage Land… and feels disturbingly at home), and Roy Thomas’ and Bernie Wrightson’s haunting adaptation of Howard’s ‘The Skull of Silence.’

To be sure, not all of it has aged smoothly. For one thing, there is a clear leitmotif about affirmative masculinity, perhaps in response to the rise of the women’s rights movement at the time. The campiest expression of this is Stan Lee’s and John Romita’s Femizons, a bizarre Wonder Woman knock-off set in a 23rd century dystopia ruled by women (who own male slaves and reproduce via sperm supplies held in the Temple of Genetics) under the suggestive moto ‘Sexuality! Solidarity! Superiority!’ The result is a cross between a preposterous parody of second wave feminism and an adolescent wet fantasy, not least because of Romita’s cheesecake artwork. (Rather than feel embarrassed by the whole thing, however, editor Roy Thomas actually let Gerry Conway bring the concept back a few years later, on the pages of Fantastic Four #151.)

BLACK HAWK

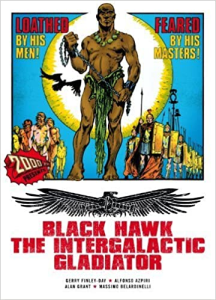

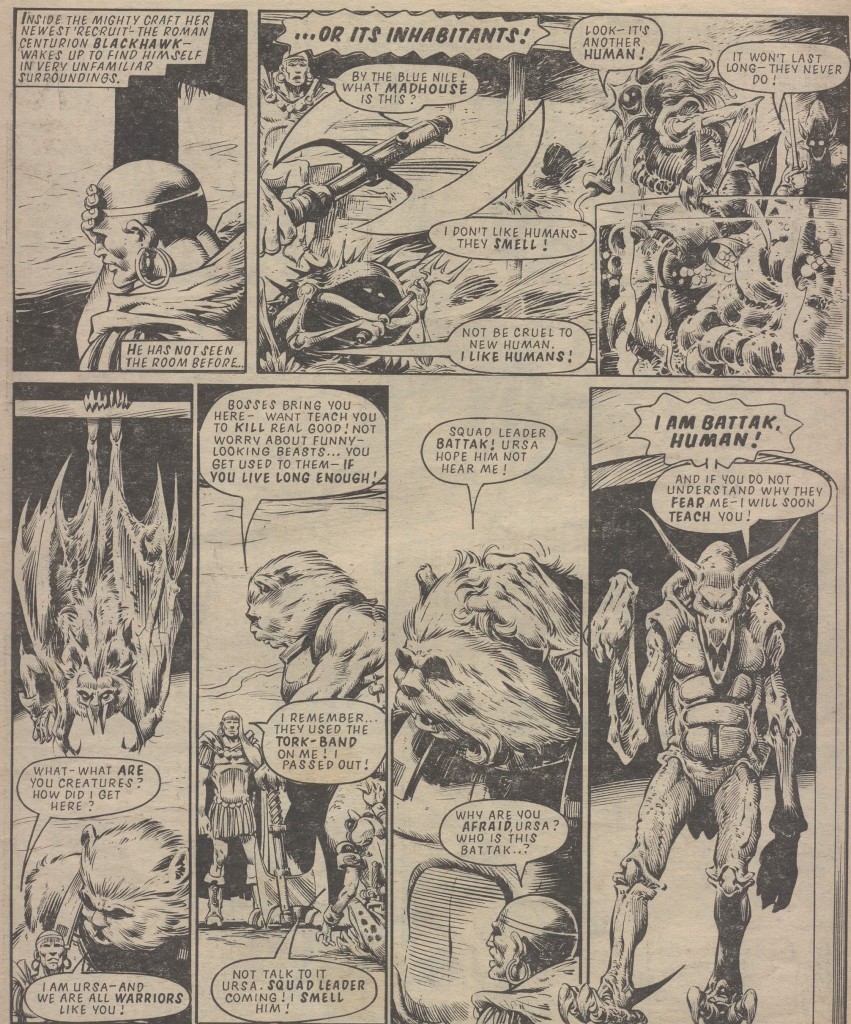

2000 AD #130

2000 AD #130

One of the most interesting aspects of Black Hawk is that it didn’t begin as an outright sci-fi/fantasy comic (although there was an ambiguous supernatural element from the start in the form of a hawk who kept helping the series’ hero). Created by Gerry Finley-Day and Alfonso Azpiri for a British anthology comic called Tornado back in the late 1970s, the series was initially set in the first century A.D. and it followed the exploits of the titular ex-slave-turned-Roman-centurion and his ragtag army of cut-throats, thieves, and lepers.

Black Hawk was a captivatingly brutal adventure yarn, even if it now seems somewhat awkward to have the narration obsessively describe the protagonist as Nubian (which, admittedly, is an important feature of the story). Because Black Hawk’s superiors loathed him, they kept sending him on suicide missions against the Roman Empire’s enemies in Germany, Judea, and Britain, so the hero had to constantly improvise and outsmart his adversaries while also keeping an eye on the untrustworthy auxiliary soldiers he commanded. Finley-Day and Azpiri were a solid team, providing at least one impressive set piece in each installment. And although Black Hawk’s peculiar loyalty to Rome wasn’t fully explored, he was certainly an honorable, charismatic hero, his ambiguous motivations making him especially intriguing.

After more than a dozen installments of ancient battles and historical cameos, however, once the series had firmly found its feet, Black Hawk was suddenly thrown into a whole new direction as the titular warrior was captured by aliens and forced to fight in an off-world arena! The radical genre shift from gripping period piece to bizarre planetary romance was caused by Tornado’s cancelation, in mid-1979. Editorial Assistant Alan Grant agreed to incorporate Black Hawk – one of Tornado’s most popular strips – into the cyberpunk magazine 2000 AD (owned by the same company), taking over writing duties alongside Kelvin Gosnell and signing with an amalgamation of their names: Alvin Gaunt. Given the improvised background of this move – and unlike what happens in Mike Grell’s similarly structured Starslayer – the stories from the Roman era never feel quite like a set-up for what’s to come (if anything, they feel like the set-up for a saga that never took place).

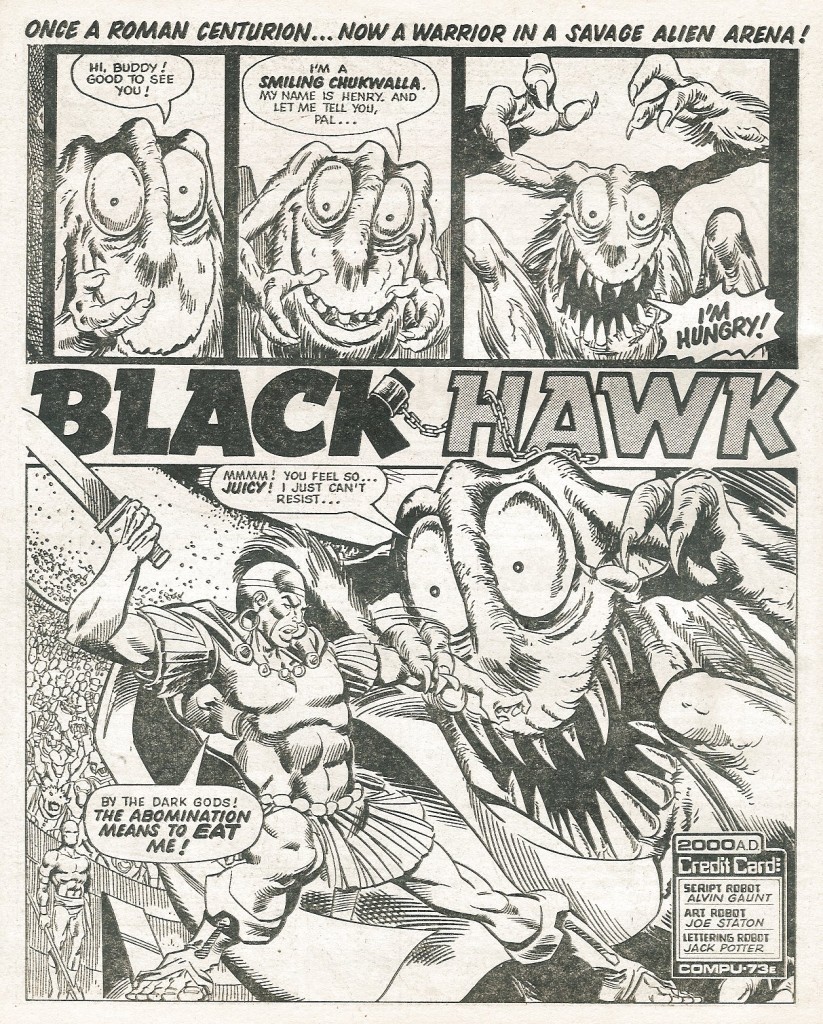

On top of this, the art changed as well, with Italian veteran Massimo Belardinelli replacing Azpiri’s dirty, cluttered Roman Empire with smoother spacescapes, neatly designed technology, and many, many weird-looking aliens. Belardinelli’s penchant for drawing smoky visuals and surreal creatures fit perfectly well with Grant’s throw-everything-at-the-wall style of storytelling (at one point, Black Hawk and his fellow gladiators are attacked by space pirates and escape into a black hole where they have to fight an evil genie!), not to mention his notorious sense of humor…

2000 AD #133

2000 AD #133

While the shift in premise and creative team was no doubt preposterous and ultimately cynical, if you read the comic in one sitting (for example, in 2011’s collected edition), there is still a curious thematic identity. The early stories were all about racism and imperial domination: even though Black Hawk joined the Roman army and fought its (also racialized) opponents, he continued to be discriminated because of his ethnicity. Moreover, his willingness to see people beyond the surface often got Black Hawk out of trouble, as he recruited handicapped soldiers who proved their worth in combat (in turn, the one time he accepted two men based on the fact that they shared his skin color, things didn’t work out so well). Despite the change of setting, the later stories kept the focus on race and slavery (the series’ logo continued to feature a metal chain) while cleverly recontextualizing it. Conveying how relative the concept of ‘race’ is, in outer space Black Hawk was no longer discriminated for being African, but for being human.

In both cases, the only way Black Hawk could earn his captors’ begrudging respect was by excelling at physical violence, essentializing him as a kind of savage. Yet, for the most part (i.e. except for the wild storyline in which a creature sucks his soul), he remains willing to bond with the strangest monsters and respect even the most outlandish adversary, whether human or alien. When he finally rebels against the cruel, exploitative intergalactic system that enslaved him, you can almost see Black Hawk finally coming to terms with his own role as servant of the Roman Empire.

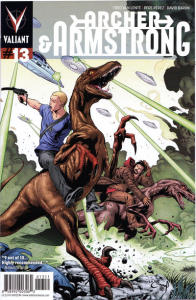

ARCHER & ARMSTRONG

(Fred Van Lente’s run)

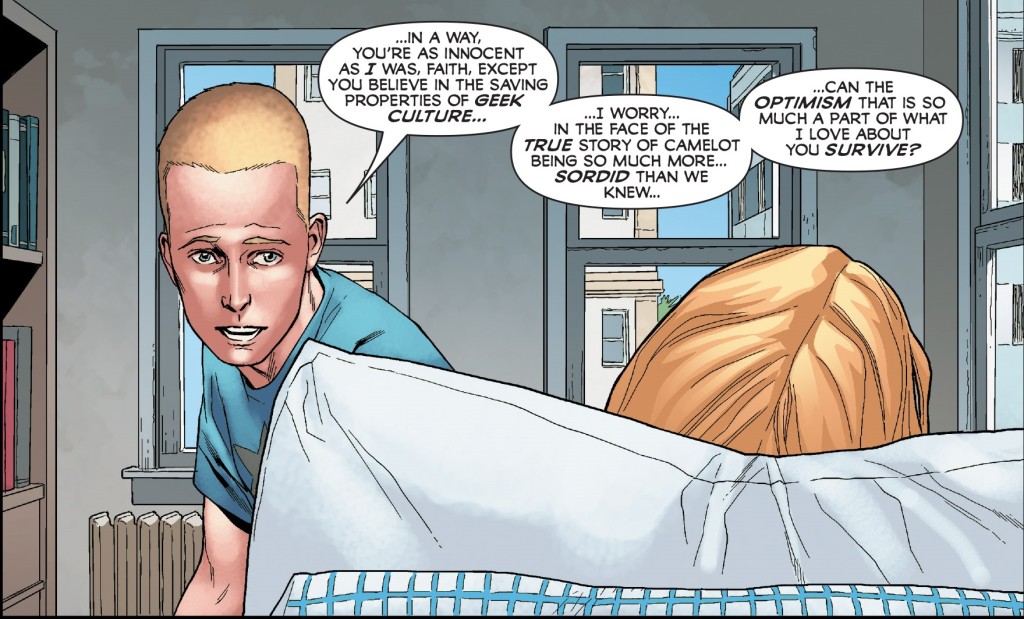

Archer & Armstrong (v2) #2

Archer & Armstrong (v2) #2

Obadiah Archer is a naïve martial arts expert raised in a creationist amusement park. Armstrong is an immortal warrior who likes to get drunk and recite poetry. In their thrilling, expertly plotted adventures, they keep saving the world from all sorts of sinister cabals, including a satanic Wall Street cult called The One Percent and a nothingness-worshiping cult called The Null (who wish to unmake the universe, turning all reality into a void). Armstrong’s origin harkens back to the Epic of Gilgamesh and, through flashbacks and a healthy dose of time travel, we learn a secret history of the Earth, one where figures such as Aristotle, Michelangelo, and Alan Turing (plus a few more surprising cameos) got involved with underground sects and supernatural conspiracies.

With this 2012 reboot of an old Valiant property, Fred Van Lente proved once again his masterful knack for penning witty sagas that effortlessly mix imaginative fantasy with topical satire. Moreover, in a field dominated by decompressed storytelling, Archer & Armstrong deserves praise for packing each issue with both non-stop action (vigorously conveyed by a host of dynamic artists: Clayton Henry, Emanuela Lupacchino, Pere Pérez, Khari Evans) and plenty of fun ideas, such as the order of ninja nuns (‘nunjas’) you see in the picture above.

Pere Pérez, in particular, proved to be the ideal partner in crime. With inventive layouts and a spotless art style that is pure eye candy, his pages have an exhilarating speed and joy, lending a truly contagious feel to Van Lente’s brand of kinetic farce. Their violent crossover with Bloodshot is a high point of the comic (it’s also more visually memorable than Vin Diesel’s Bloodshot movie earlier this year, even if I appreciate the latter’s meta discourse on action tropes…). Plus, Pérez’s and Van Lente’s work on the Ivar, Timewalker spin-off is somehow even more hectic! (They then brought their combined magic to Marvel, with the Deadpool versus The Punisher mini-series.)

If you are inclined that way, you can read in Fred Van Lente’s run – plus in Ivar, Timewalker and its brilliant follow-up, Vault of Spirits – a commentary on humanity’s compulsion towards intolerant belief systems, in politics as well as religion. The trippiest arc, ‘American Wasteland,’ also delves into our society’s obsession with dead celebrities, simultaneously exploiting the allure of pop culture and denouncing its role as a modern mythology – one with many of the trappings of older mythologies (a point revisited in The Tale of the Green Knight one-shot). This iconoclastic strain gives Van Lente’s work a depth that may not be immediately apparent amongst all the slapstick and violence.

Immortal Brothers: The Tale of the Green Knight

Immortal Brothers: The Tale of the Green Knight

Sadly, subsequent writers didn’t do justice to this approach… The worst offense took place in 2016’s Stalinverse event about a hallucinated version of reality in which the Soviet Union took over the world. What could have been a nifty pretext to imaginatively envisage Valiant characters in a socialist setting – like Red Son did for Superman – boiled down to old Cold War stereotypes, its lazy version of communism merely a generic dictatorship colored with recognizable slogans and symbols. One of the few issues to attempt to address ideology – albeit in a clumsy, simplistic way that misses the mark on the USSR’s ambiguous relationship with religion – was the one-shot Escape from Gulag 396 (written by Eliot Rahal), in which Archer helps Armstrong gain faith in God… This could’ve been a provocative way to suggest that oppression can strengthen belief or even a tongue-in-cheek gag about how upside-down the world had become, but the ending comes across as bafflingly irony-free.

To end on a positive note, though, I should point out that, in turn, Jody Houser’s mini-series Faith and the Future Force is a worthy sequel to Ivar, Timewalker, doubling down on the Doctor Who riffs while filling each page with mind-bending concepts through a neat mix of adrenaline and hilarity.