As far as remakes go, I’m of the school of leave-good-works-alone-and-remake-the-bad-ones-instead. To use John Carpenter’s oeuvre as an example (as I often do), I can understand the financial urge to bank on title recognition, but artistically I see no point in doing bland remakes of Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween (or even The Fog), which are already fine films that people can watch whenever they feel like… Wouldn’t it make more sense to have someone polish the many flaws of Ghosts of Mars and give all those interesting ideas the awesome movie they deserve?

That said, the coolest remakes are the ones that go beyond lazily redoing the plot beat-for-beat while adding little more than glitz, or perhaps an alternative setting. If you’re going to revisit an existing story, then you might as well put a spin on the characters or approach the material with a significantly different vibe. For example, I liked how, instead of merely relocating Jorge Michel Grau’s We Are What We Are (which was basically a dark metaphor for urban malaise in Mexico City), Jim Mickle worked the premise into a whole other type of tale, crafting a beautifully intense psychological horror film that takes inspiration from the disturbing original yet still feels somewhat unique. What’s more, some projects can be interesting just by virtue of being made in distant eras. The remakes of RoboCop or Invasion of the Body Snatchers may not stand out on their own, but it’s appealing to see how they reflect multiple zeitgeists.

This is something I keep thinking about when reading superhero comics, which have a tendency to tell variations of the same stories over and over again (quick: how many versions of Batman’s first encounter with the Joker are there?). The latter, I suspect, is not only the product of pop-will-eat-itself, but also of the huge weight of nostalgia on fans-turned-creators, plus all the reboots and parallel continuities that have become a staple of the genre.

With all this in mind, I decided to take a look at the various remakes of ‘The Case of the Chemical Syndicate.’

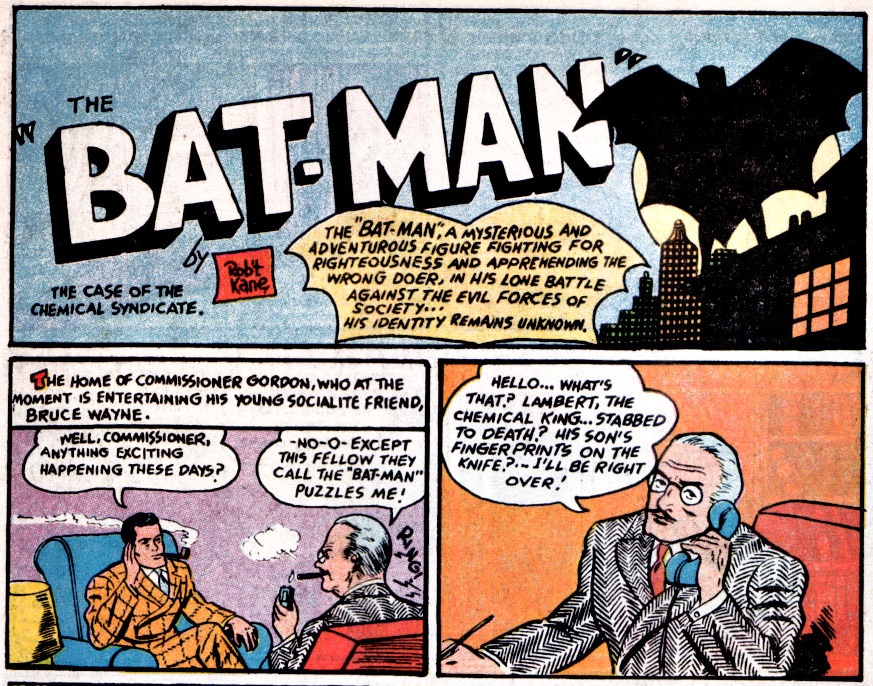

Originally published in 1939, the six-page ‘The Case of the Chemical Syndicate’ (Detective Comics #27), by Bob Kane and an uncredited Bill Finger, was the first comic to feature Batman (or the Bat-Man, as he was called at the time). The plot is a modest, no-frills whodunit – swiped from a Shadow short story – about the murder of a chemical industrialist called Lambert. Neatly, the Dark Knight shows off what would become his trademarks: he punches crooks (three times), escapes from a deathtrap (a gas chamber for guinea pigs), and deduces the solution to the mystery. There are some rough edges, for sure, but I love the fact that the very final twist is the revelation that the Bat-Man is actually the rich socialite Bruce Wayne! (Sorry for the mega-spoiler.)

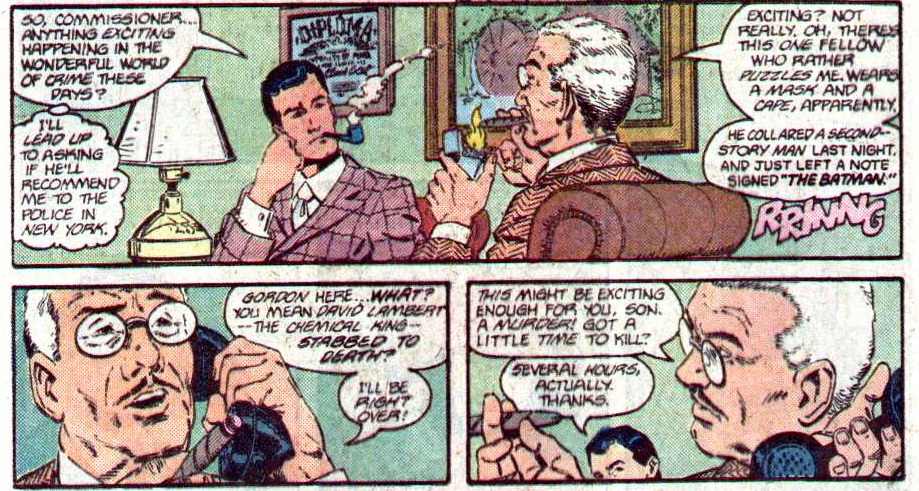

In 1969, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Caped Crusader’s debut, editor Julie Schwarz asked teenager Mike Friedrich to write an updated version of this tale, illustrated by the art team of Bob Brown and Joe Giella. This remake (published in Detective Comics #387) makes it clear from the start that the times are a-changin’, with the very first panel mentioning the fear of atomic war:

Plot-wise, Friedrich follows the murder mystery structure quite closely but, in an inspired move, he takes a small scene from the original about Lambert’s son being the prime suspect and makes this the heart of the story, thus imbuing it with the late ‘60s generation gap!

Indeed, the comic takes every opportunity to channel the time period. There are plenty of delightfully slangy lines, such as ‘It’s just, like, you’ve become so warped by the system you just can’t dig it’ or ‘This whole scene is one big bummer, but I don’t hafta hack it, so I’m splittin’!’ And after using the peace movement as a red herring, the story finishes on a poignant (if ham-fisted) note, arguing both against condemning hippie youth just based on its rude behavior and against indiscriminately rebelling against authority just for rebellion’s sake. It’s a tight, sweet tale that shows Batman comics keeping up with the times. That said, some changes took longer than others: like in the original, there is not a single female character in sight (unless you count the Janis Joplin reference early on).

Roy Thomas and Marshall Rogers revisited the tale once again in 1986, as part of Secret Origins #6. This is a less interesting remake… Since the point of that issue is just to retell the debut of the Golden Age Batman and since Roy Thomas was notoriously nostalgic about old comics, the result is boringly close to the original, albeit with lavisher art:

Still, the weight of almost fifty years of stories could not help but leave a mark. In the 1939 comic, the Dark Knight was still close to his pulp origins, including a more flexible relationship with the limits of vigilante justice… He basically killed the baddie in the end by punching him into an acid tank – and while the Bat-Man didn’t necessarily mean to do it, he didn’t seem to mind too much either, infamously postulating: ‘A fitting ending for his kind.’ The 1986 version keeps the callous line but, in one of the few departures from the original, this time around the villain falls into the acid without getting punched by the Caped Crusader.

More remarkably, five years later, in Detective Comics #627, DC reprinted the original story and the 1969 remake, together with two new variations done by contemporary writers and artists. (Also, for some weird reason, they changed the title of Mike Friedrich’s version, from ‘The Cry of Night is – Sudden Death!’ to ‘The Cry of Night is – Kill!’)

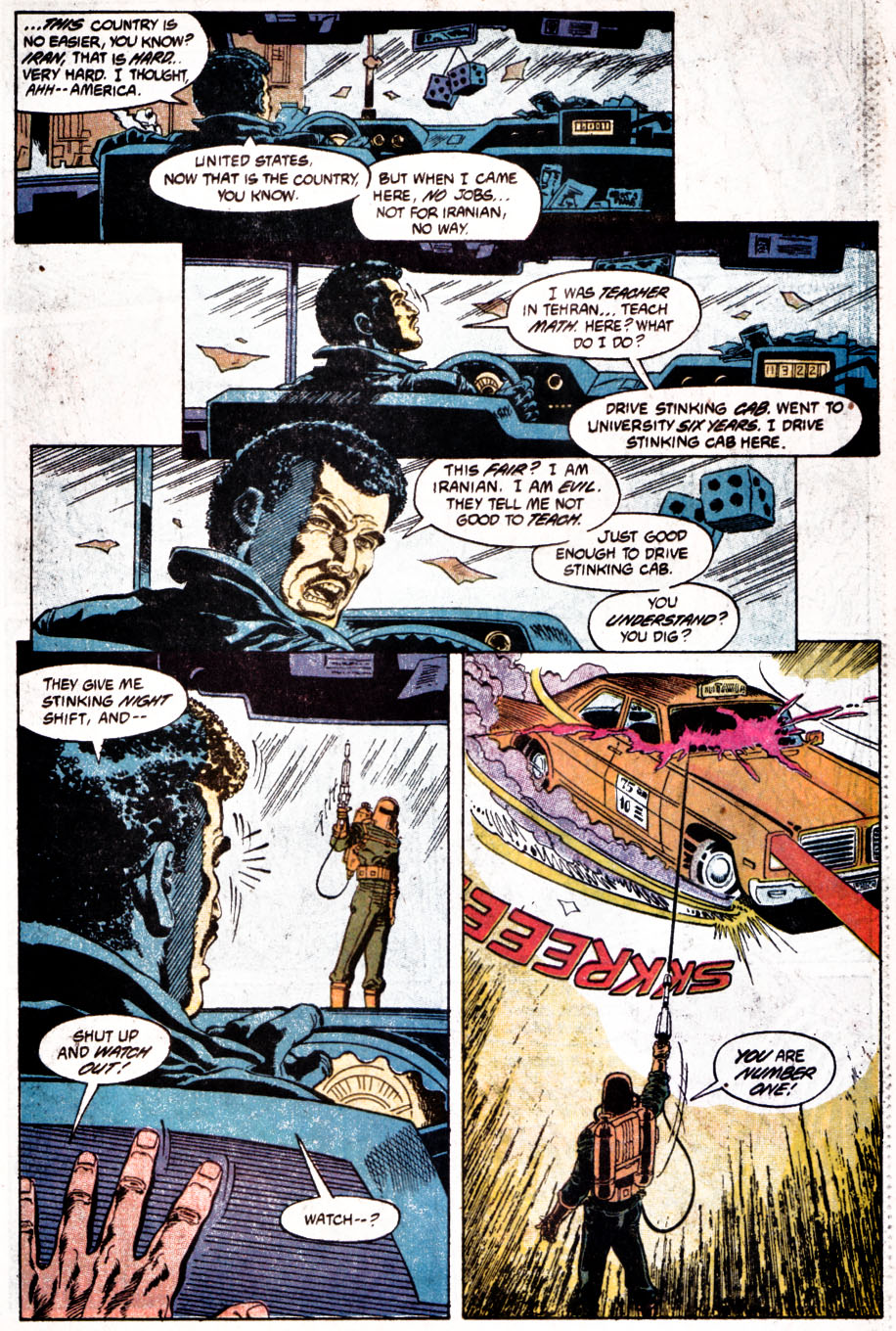

The new tales were quite something. The remake by Marv Wolfman and Jim Aparo lifts the original’s opening narration, but it quickly modernizes the setting with references to the rampant anti-Iranian sentiment of the early 1990s, due to that nation’s links to terrorism in the previous decade…

While keeping the basic outline, the plot is more elaborate than in the original, even if Batman’s detective work isn’t all that impressive. Wolfman and Aparo also amp up the action, creating a new costumed villain for the occasion – the rather lame Pesticyde. This take reimagines several other details, building up on Friedrich’s introduction of generational conflict into the story. Since the Cold War was practically over by then, however, Lambert’s son no longer rebels against his father because of the company’s contribution to the arms race, but because his company is polluting the environment.

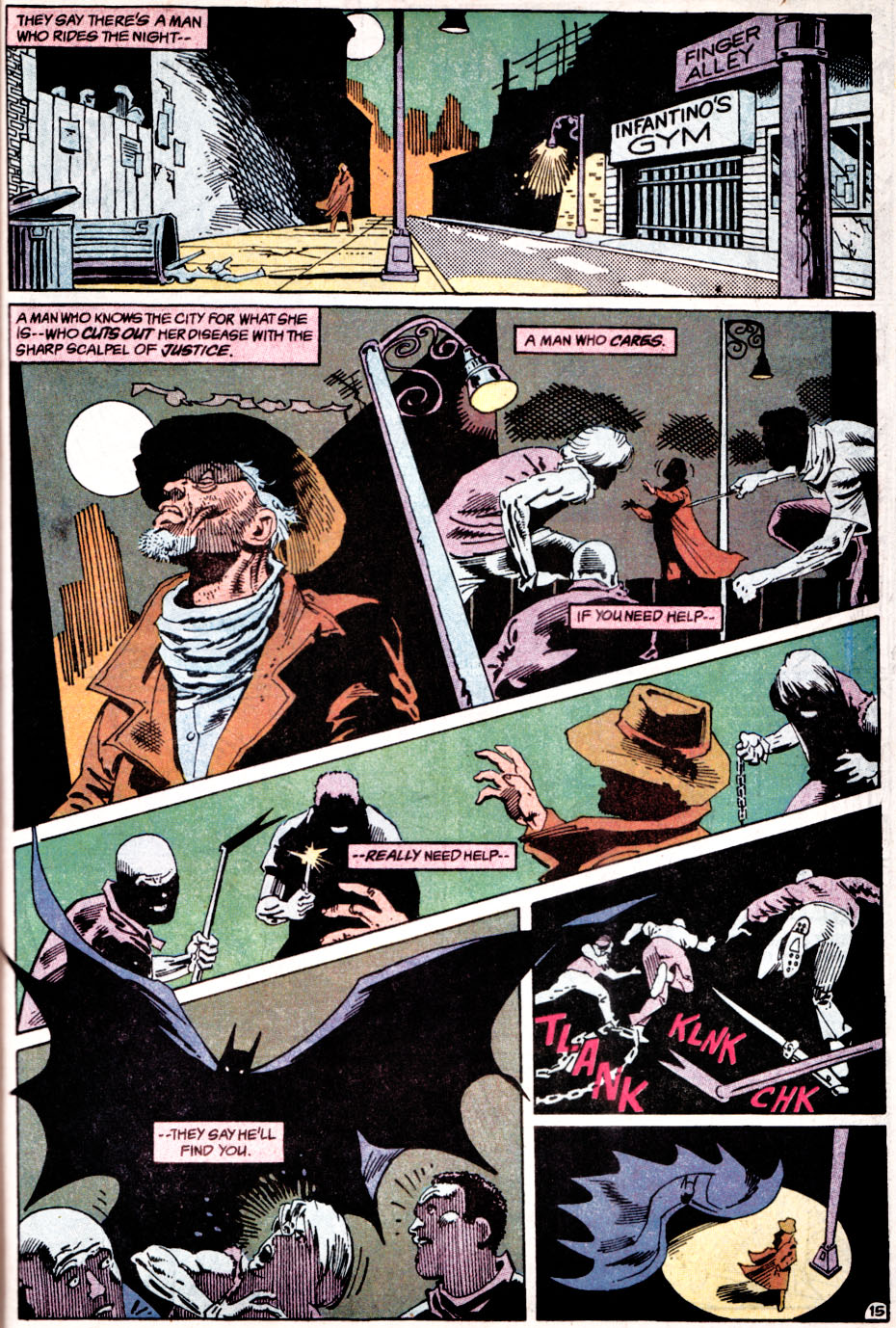

Likewise, the wonder team of Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle bluntly shove a toxic waste angle into their remake of ‘The Case of the Chemical Syndicate.’ Needless to say with these two, their section of the comic crackles with berserk energy. Breyfogle’s art jumps off the page, culminating in a wonderful final splash. Plus, like in most Batman tales written by Grant at the time, there is a subplot about drugs… And just to make the whole affair even more nineties, the Dark Knight is frighteningly ruthless and Gotham City looks gritty as hell:

(Despite the grim tone, letterer Todd Klein helps give the comic a lighter touch by squeezing references to several classic creators and editors into every sign and headline he can find.)

Finally, a couple of years ago, Brad Meltzer and Bryan Hitch added their own remake, in the latest volume of Detective Comics #27. This one is pretty lackluster, without any of the charm of its predecessors: there is no attempt to unfold a proper mystery, to create interesting character dynamics, or to resonate with topical concerns. In fact, there is nothing particularly inspired going on (even the reveal in the last panel is kind of ‘meh’), which, I suppose, fairly reflects the lack of creativity in the early years of the New 52 bat-books… Furthermore, Batman keeps justifying his decision to fight crime through an unbelievably cheesy voice-over throughout the comic (‘I do it because there’s nothing more powerful than an ordinary person. I do it because there’s no such thing as an ordinary person.’). Yep, it’s as bad as it sounds – and it doesn’t even look good – but at least there is a moment in which Meltzer really gets to the very heart of the Dark Knight:

No wonder Batman is always so pissed. He’s missing some great movies…